14 Examples of Formative Assessment [+FAQs]

Traditional student assessment typically comes in the form of a test, pop quiz, or more thorough final exam. But as many teachers will tell you, these rarely tell the whole story or accurately determine just how well a student has learned a concept or lesson.

That’s why many teachers are utilizing formative assessments. While formative assessment is not necessarily a new tool, it is becoming increasingly popular amongst K-12 educators across all subject levels.

Curious? Read on to learn more about types of formative assessment and where you can access additional resources to help you incorporate this new evaluation style into your classroom.

What is Formative Assessment?

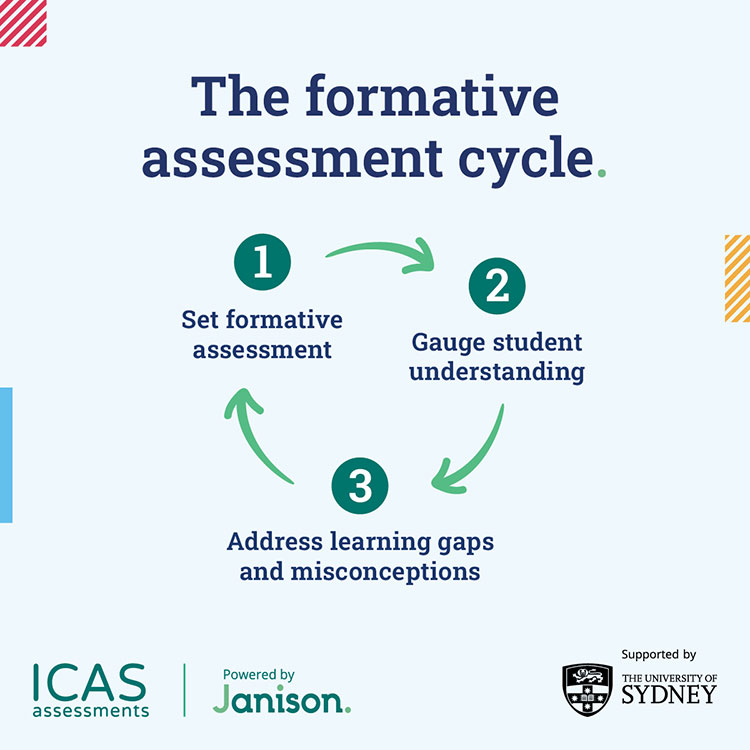

Online education glossary EdGlossary defines formative assessment as “a wide variety of methods that teachers use to conduct in-process evaluations of student comprehension, learning needs, and academic progress during a lesson, unit, or course.” They continue, “formative assessments help teachers identify concepts that students are struggling to understand, skills they are having difficulty acquiring, or learning standards they have not yet achieved so that adjustments can be made to lessons, instructional techniques, and academic support.”

The primary reason educators utilize formative assessment, and its primary goal, is to measure a student’s understanding while instruction is happening. Formative assessments allow teachers to collect lots of information about a student’s comprehension while they’re learning, which in turn allows them to make adjustments and improvements in the moment. And, the results speak for themselves — formative assessment has been proven to be highly effective in raising the level of student attainment, increasing equity of student outcomes, and improving students’ ability to learn, according to a study from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

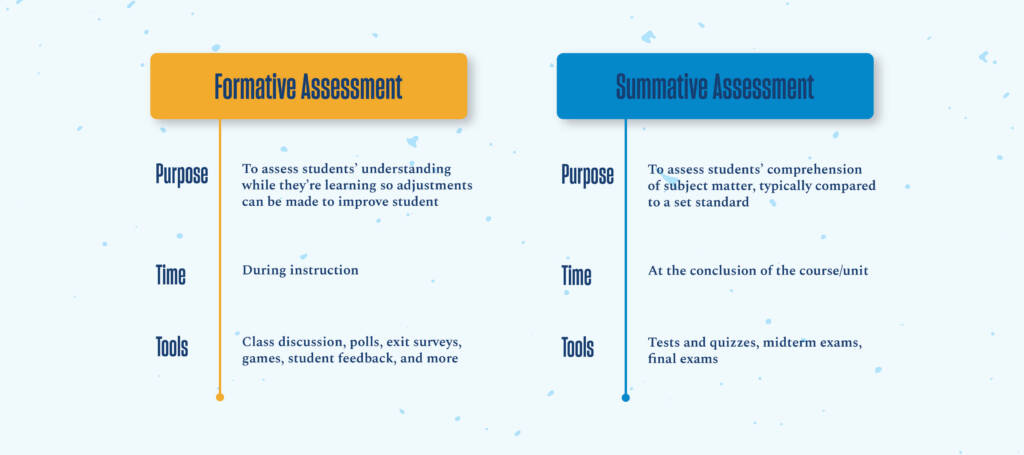

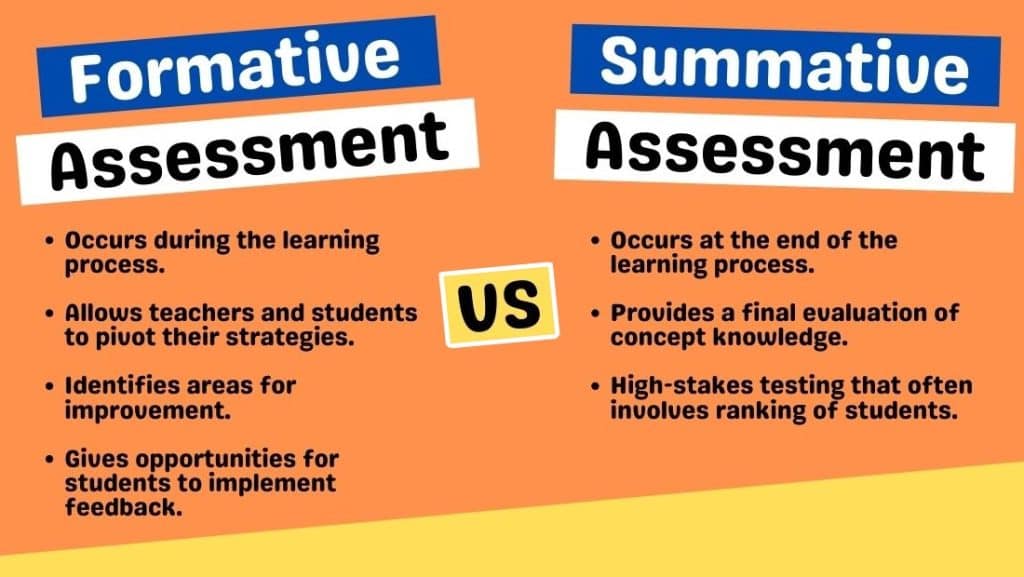

On the flipside of the assessment coin is summative assessments, which are what we typically use to evaluate student learning. Summative assessments are used after a specific instructional period, such as at the end of a unit, course, semester, or even school year. As learning and formative assessment expert Paul Black puts it, “when the cook tastes the soup, that’s formative assessment. When a customer tastes the soup, that’s summative assessment.”

14 Examples of Formative Assessment Tools & Strategies

There are many types of formative assessment tools and strategies available to teachers, and it’s even possible to come up with your own. However, here are some of the most popular and useful formative assessments being used today.

- Round Robin Charts

Students break out into small groups and are given a blank chart and writing utensils. In these groups, everyone answers an open-ended question about the current lesson. Beyond the question, students can also add any relevant knowledge they have about the topic to their chart. These charts then rotate from group to group, with each group adding their input. Once everyone has written on every chart, the class regroups and discusses the responses.

- Strategic Questioning

This formative assessment style is quite flexible and can be used in many different settings. You can ask individuals, groups, or the whole class high-level, open-ended questions that start with “why” or “how.” These questions have a two-fold purpose — to gauge how well students are grasping the lesson at hand and to spark a discussion about the topic.

- Three-Way Summaries

These written summaries of a lesson or subject ask students to complete three separate write-ups of varying lengths: short (10-15 words), medium (30-50 words), and long (75-100). These different lengths test students’ ability to condense everything they’ve learned into a concise statement, or elaborate with more detail. This will demonstrate to you, the teacher, just how much they have learned, and it will also identify any learning gaps.

- Think-Pair-Share

Think-pair-share asks students to write down their answers to a question posed by the teacher. When they’re done, they break off into pairs and share their answers and discuss. You can then move around the room, dropping in on discussions and getting an idea of how well students are understanding.

Looking for a competitive edge? Explore our Education certificate options today! >

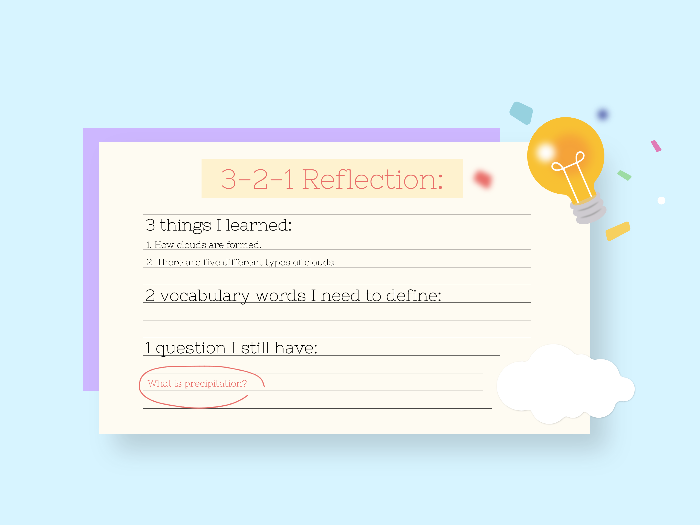

- 3-2-1 Countdown

This formative assessment tool can be written or oral and asks students to respond to three very simple prompts: Name three things you didn’t know before, name two things that surprised you about this topic, and name one you want to start doing with what you’ve learned. The exact questions are flexible and can be tailored to whatever unit or lesson you are teaching.

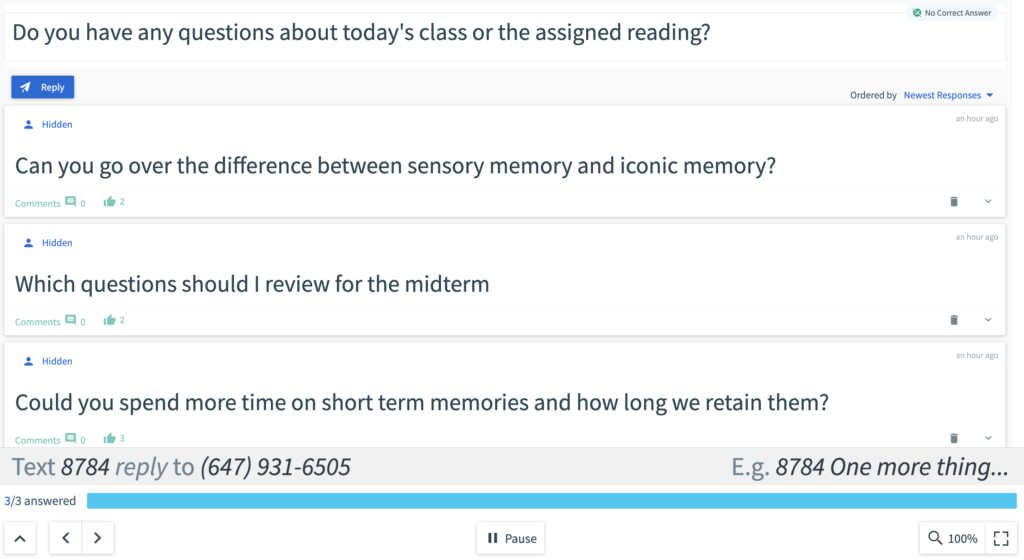

- Classroom Polls

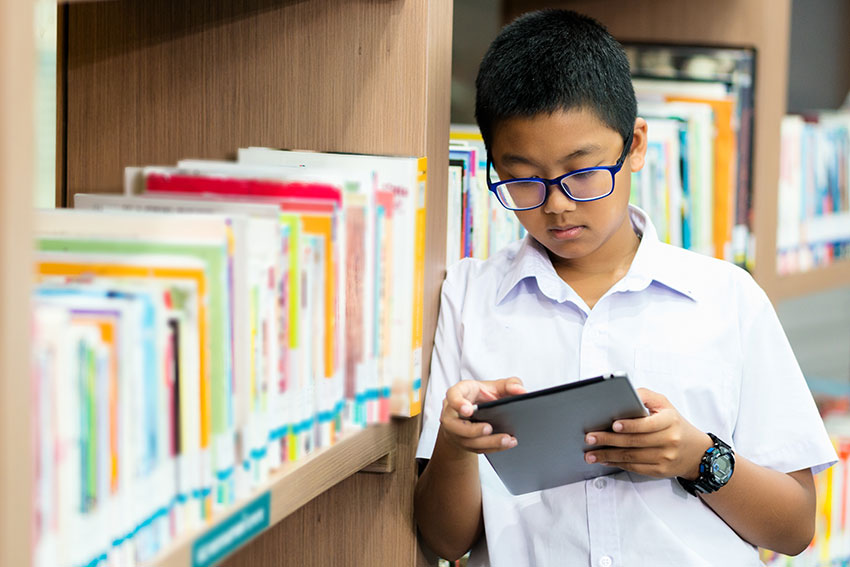

This is a great participation tool to use mid-lesson. At any point, pose a poll question to students and ask them to respond by raising their hand. If you have the capability, you can also use online polling platforms and let students submit their answers on their Chromebooks, tablets, or other devices.

- Exit/Admission Tickets

Exit and admission tickets are quick written exercises that assess a student’s comprehension of a single day’s lesson. As the name suggests, exit tickets are short written summaries of what students learned in class that day, while admission tickets can be performed as short homework assignments that are handed in as students arrive to class.

- One-Minute Papers

This quick, formative assessment tool is most useful at the end of the day to get a complete picture of the classes’ learning that day. Put one minute on the clock and pose a question to students about the primary subject for the day. Typical questions might be:

- What was the main point?

- What questions do you still have?

- What was the most surprising thing you learned?

- What was the most confusing aspect and why?

- Creative Extension Projects

These types of assessments are likely already part of your evaluation strategy and include projects like posters and collage, skit performances, dioramas, keynote presentations, and more. Formative assessments like these allow students to use more creative parts of their skillset to demonstrate their understanding and comprehension and can be an opportunity for individual or group work.

Dipsticks — named after the quick and easy tool we use to check our car’s oil levels — refer to a number of fast, formative assessment tools. These are most effective immediately after giving students feedback and allowing them to practice said skills. Many of the assessments on this list fall into the dipstick categories, but additional options include writing a letter explaining the concepts covered or drawing a sketch to visually represent the topic.

- Quiz-Like Games and Polls

A majority of students enjoy games of some kind, and incorporating games that test a student’s recall and subject aptitude are a great way to make formative assessment more fun. These could be Jeopardy-like games that you can tailor around a specific topic, or even an online platform that leverages your own lessons. But no matter what game you choose, these are often a big hit with students.

- Interview-Based Assessments

Interview-based assessments are a great way to get first-hand insight into student comprehension of a subject. You can break out into one-on-one sessions with students, or allow them to conduct interviews in small groups. These should be quick, casual conversations that go over the biggest takeaways from your lesson. If you want to provide structure to student conversations, let them try the TAG feedback method — tell your peer something they did well, ask a thoughtful question, and give a positive suggestion.

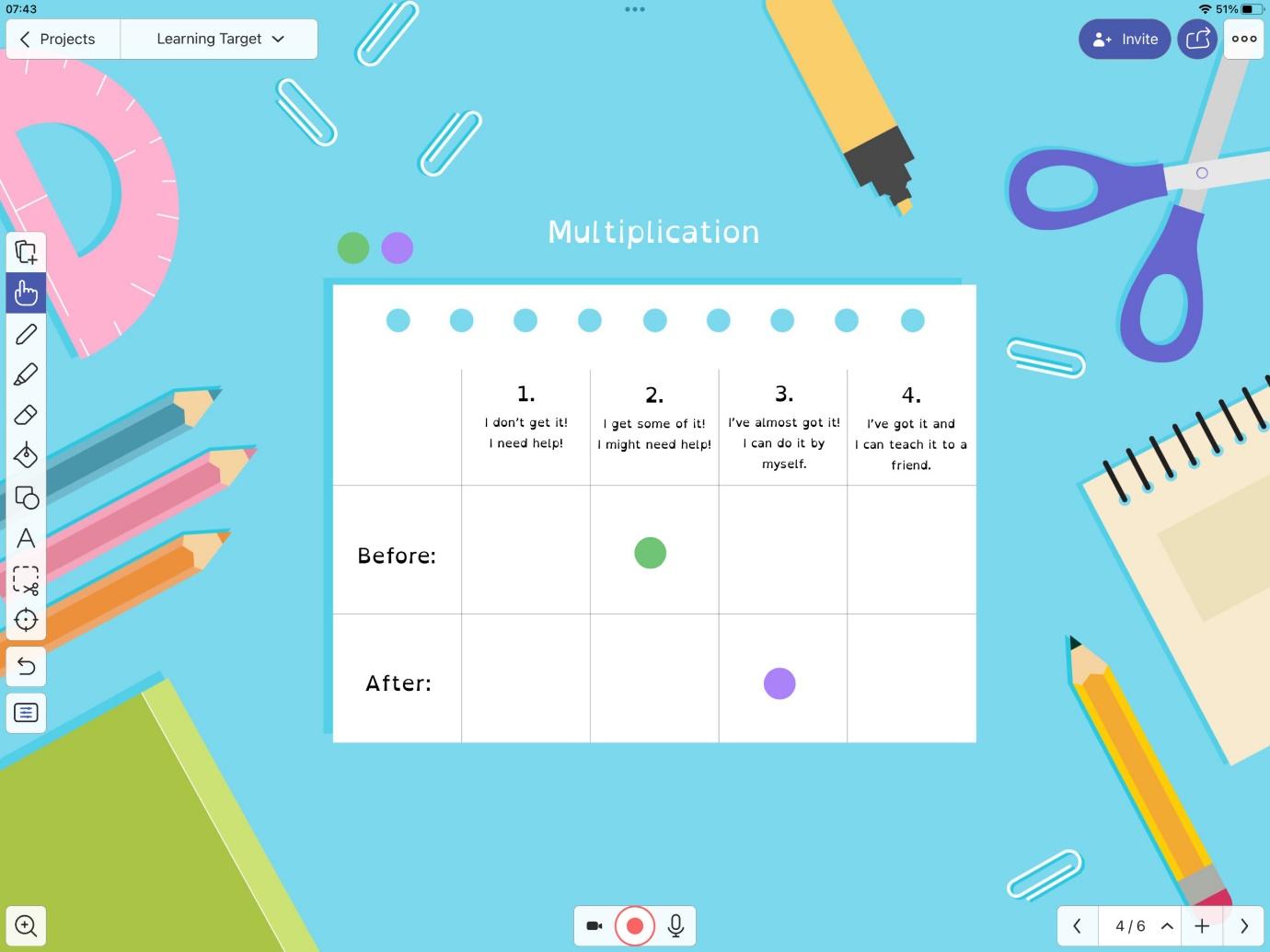

- Self Assessment

Allow students to take the rubric you use to perform a self assessment of their knowledge or understanding of a topic. Not only will it allow them to reflect on their own work, but it will also very clearly demonstrate the gaps they need filled in. Self assessments should also allow students to highlight where they feel their strengths are so the feedback isn’t entirely negative.

- Participation Cards

Participation cards are a great tool you can use on-the-fly in the middle of a lesson to get a quick read on the entire classes’ level of understanding. Give each student three participation cards — “I agree,” “I disagree,” and “I don’t know how to respond” — and pose questions that they can then respond to with those cards. This will give you a quick gauge of what concepts need more coverage.

5 REASONS WHY CONTINUING EDUCATION MATTERS FOR EDUCATORS

The education industry is always changing and evolving, perhaps now more than ever. Learn how you can be prepared by downloading our eBook.

List of Formative Assessment Resources

There are many, many online formative assessment resources available to teachers. Here are just a few of the most widely-used and highly recommended formative assessment sites available.

- Arizona State Dept of Education

FAQs About Formative Assessment

The following frequently asked questions were sourced from the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD), a leading education professional organization of more than 100,000 superintendents, principals, teachers, and advocates.

Is formative assessment something new?

No and yes. The concept of measuring a student’s comprehension during lessons has existed for centuries. However, the concept of formative assessment as we understand it didn’t appear until approximately 40 years ago, and has progressively expanded into what it is today.

What makes something a formative assessment?

ASCD characterized formative assessment as “a way for teachers and students to gather evidence of learning, engage students in assessment, and use data to improve teaching and learning.” Their definition continues, “when you use an assessment instrument— a test, a quiz, an essay, or any other kind of classroom activity—analytically and diagnostically to measure the process of learning and then, in turn, to inform yourself or your students of progress and guide further learning, you are engaging in formative assessment. If you were to use the same instrument for the sole purpose of gathering data to report to a district or state or to determine a final grade, you would be engaging in summative assessment.”

Does formative assessment work in all content areas?

Absolutely, and it works across all grade levels. Nearly any content area — language arts, math, science, humanities, and even the arts or physical education — can utilize formative assessment in a positive way.

How can formative assessment support the curriculum?

Formative assessment supports curricula by providing real-time feedback on students’ knowledge levels and comprehension of the subject at hand. When teachers regularly utilize formative assessment tools, they can find gaps in student learning and customize lessons to fill those gaps. After term is over, teachers can use this feedback to reshape their curricula.

How can formative assessment be used to establish instructional priorities?

Because formative assessment supports curriculum development and updates, it thereby influences instructional priorities. Through student feedback and formative assessment, teachers are able to gather data about which instructional methods are most (and least) successful. This “data-driven” instruction should yield more positive learning outcomes for students.

Can formative assessment close achievement gaps?

Formative assessment is ideal because it identifies gaps in student knowledge while they’re learning. This allows teachers to make adjustments to close these gaps and help students more successfully master a new skill or topic.

How can I help my students understand formative assessment?

Formative assessment should be framed as a supportive learning tool; it’s a very different tactic than summative assessment strategies. To help students understand this new evaluation style, make sure you utilize it from the first day in the classroom. Introduce a small number of strategies and use them repeatedly so students become familiar with them. Eventually, these formative assessments will become second nature to teachers and students.

Before you tackle formative assessment, or any new teaching strategy for that matter, consider taking a continuing education course. At the University of San Diego School of Professional and Continuing Education, we offer over 500 courses for educators that can be completed entirely online, and many at your own pace. So no matter what your interests are, you can surely find a course — or even a certificate — that suits your needs.

Be Sure To Share This Article

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Your Salary

Browse over 500+ educator courses and numerous certificates to enhance your curriculum and earn credit toward salary advancement.

Related Posts

Improving Student Writing Through Formative Assessments

Making the writing connection, what is formative feedback, monitoring progress, the time is write.

Premium Resource

Is Writing in Crisis?

Writing is crucial to success in college, a career, and life in general. Despite writing's pivotal role, several indicators point to a nationwide crisis in the skill.

"Policies have been shaped by misconceptions that writing cannot be taught or assessed," says Graham. In reality, writing can be taught and assessed—but it requires a significant investment in teacher training and improved summative assessments, he notes.

Studies show that two out of three students don't write well enough to meet grade level. In classrooms, less time is spent on writing instruction, and students have fewer opportunities to write, especially writing that involves analysis and interpretation.

"The Nation's Report Card," by the National Assessment of Education Progress, reports broad trends in subject-specific achievement across the United States. In 2007, the report showed small gains in writing, but these gains may have masked the fact that only a third of 8th graders and less than a quarter of high school seniors tested at or above the proficient level, writes Gavin Tachibana in the article, "'Nation's Report Card' Shows Modest Improvement in Students' Writing Scores."

Basically, two out of three students don't write well enough to meet grade level, say the Informing Writing researchers. And, employers and college students are spending billions every year for remedial writing courses. For example, almost a third of all incoming freshmen (attending community and four-year colleges) take at least one remedial course; about a quarter of those remedial courses are in writing, according to the 2006 Alliance for Excellent Education report Paying Double: Inadequate High Schools and Community College Remediation .

<P EXCERPT="yes" ALPHABET="latin" SDAFORM="para"> <!-- Start of Brightcove Player --> <!--div style="display:none"> </div--> <!--By use of this code snippet, I agree to the Brightcove Publisher T and C found at https://accounts.brightcove.com/en/terms-and-conditions/. --> <!-- insert video here brightcove information : http://video.ascd.org/services/player/bcpid18377529001?bckey=AQ~~,AAAAAmGjiRE~,escbD3Me8-wT_coVb7sTe18vG6vv3Oyk&bctid=1377612042001--> <!-- This script tag will cause the Brightcove Players defined above it to be created as soonas the line is read by the browser. If you wish to have the player instantiated only afterthe rest of the HTML is processed and the page load is complete, remove the line.--> <!-- End of Brightcove Player -->

ASCD is a community dedicated to educators' professional growth and well-being.

Let us help you put your vision into action..

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, how to properly implement a formative writing assessment over a year.

Formative assessment can be tricky — especially for a subject like writing — but it is an essential part of any plan to ensure student success.

Tests, or assessments in the educational vernacular, come in two major varieties:

- Summative assessments, which evaluate a student’s progress at the end of a year or course.

- Formative assessments, which monitor the progress of student learning throughout the year.

Though grading students via summative assessment typically receives a lot of attention from students, parents and policymakers, formative assessments are essential because they give teachers a better idea of how to adapt their instructions to meet the needs of the students. These tips offer guidance on properly implementing formative writing assessment in the classroom.

Charting Daily Progress with In-Class Formative Writing Assessments

At the beginning of the year, teachers can give students a simple diagnostic writing test to establish a baseline of students’ writing skill, both individually and as a class.

When handing back diagnostics with comments, teachers can ask students to write for one to three minutes in response to the feedback they received. This will open up a dialogue around their writing process that will shift the focus away from summative grades and towards the process of writing, thinking about writing, and improving writing. Using this technique on all formal writing assignments can help students practice meta-cognition, which can improve their critical-thinking skills.

Exit tickets are another great way to prompt meta-cognition. These short, simple daily assignments can measure the main objective being taught on a larger level. Teachers should give the students no more than two questions, and try to keep one question concrete and allow the other question to require more explanation. Then, the teacher can tally the results of the exit tickets each day to measure class mastery and pinpoint enduring weaknesses.

Maximizing the Benefits of Homework, Quizzes and Tests

Traditional weekly homework assignments provide a great way to measure progress because they show how students write outside the controlled environment of a classroom. Teachers should require students to go beyond simple answers in their quizzes and tests and ask open-ended questions that require thorough explanation of their thinking. Their answers will be more revealing, and give better data to inform future instruction.

Generating Student Feedback and Reflection

It always helps to require students to give you feedback on the day’s writing practice. In examining student feedback and reflection, be on the lookout for misconceptions. Here are a few approaches to that:

- Direct refutation: Let students know their thinking is simply incorrect.

- Provide examples that point out why the misconceptions are not reasonable.

- Offer visual models that give students an alternative way of understanding.

- Engage students in thinking by teaching active-learning strategies so they get out of the habit of learning passively.

The more teachers use formative writing assessment, the better equipped they’ll be to address misconceptions and understand the progress their students are making toward the goal of improving as writers, thinkers, and students.

You may also like to read

- These 4 End-of-the-Year Writing Projects are Sure Bets for Engaging and Exciting Your Students

- 3 Types of Assessment Commonly Used in Education

- 4 Tips for Teaching 2nd Grade Writing

- How Teachers Can Increase the Impact of Essay Writing for Students

- School District Debate: Year-Round Schools

- 4 Prompts To Get Middle School Kids Writing

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

- Math Teaching Resources | Classroom Activitie...

- PhD Programs for Education

- Master's in Education Technology & Learning D...

- MyU : For Students, Faculty, and Staff

Writing Across the Curriculum

- Research & Assessment

- Writing Plans

- WEC Liaisons

- Academic Units

- Engage with WEC

- Teaching Resources

- Teaching Consultations

- Faculty Writing Resources

Creating and Using Formative Writing Assignments

As writers, we know that writing is a process that takes place over time and is made up of different sorts of intellectual activities. As instructors, however, we often assign writing tasks as large, single assignments at the end of a semester. This can be too late for feedback to be meaningful or effective for future use and can encourage students to procrastinate until the last minute. By breaking up these large writing assignments into smaller “formative” assignments, you can not only provide more timely feedback but also better train students to approach writing as a process made up of different, equally important intellectual activities.

Formative assignments are low-stake, high-value smaller assignments that are later brought together into larger, cumulative assignments. For example, instead of assigning a single writing project all at once, you might schedule a series of small assignments that, for instance, require students to summarize the theories they’ve studied, analyze the evidence they will be using, and formulate and present the question and thesis to be addressed. After students have received feedback on each of these component parts, they bring them all together into the larger assignment.

There are many benefits to breaking up large assignments into smaller, formative assignments

- They encourage students to think of writing as an ongoing, developing process rather than as a single activity done all at once.

- They can keep students on track in terms of both time and content (by, for example, helping them avoid writing an entire assignment at the last minute on a bad or misguided idea).

- Rather than piling up all your own feedback work at once, they allow you to spread it out and give immediate, targeted feedback to the intellectual task at hand.

- They emphasize and target specific skills for the course or discipline (for example, source use, results discussion, and so on).

How to write formative assignments

Break a large writing assignment into its component pieces (e.g., introduction, conclusion, summary, methods, etc.).

- Prepare explicit directions for each piece. For example, provide specific explanations for what belongs in a successful introduction, or what a summary component requires, and so on. ( The best instructions also tell students why these things are required .)

- Prepare straightforward rubrics for evaluating the assignment according to the given directions.

- For example, if the first thing students need to do is analyze evidence, have them complete this assignment first; if the last thing they should do is write the introduction, have them complete this assignment last.

Use assignments to target potential stumbling blocks for students; if, for instance, you know students struggle with thesis development or counterargument, create assignments focused on these areas.

Formative assignments can also focus on specific writing conventions of the discipline, such as tone, voice, terminology, use of sources, and so on.

- WAC Clearinghouse, “Sequencing Writing Assignments”

- MIT Comparative Media Studies/Writing, “Sequencing Writing Assignments”

- Kate Kiefer, “Examples of Writing to Learn Activities”

- University of Minnesota Center for Writing, “Informal, In-class Writing Activities”

Further Support

Visit us online at http://writing.umn.edu/tww. To schedule a phone, email, or face-to-face teaching consultation, click here.

- Log in to post comments

- African American & African Studies

- Agronomy and Plant Genetics

- Animal Science

- Anthropology

- Applied Economics

- Art History

- Carlson School of Management

- Chemical Engineering and Materials Science

- Civil, Environmental, and Geo- Engineering

- College of Biological Sciences

- Communication Studies

- Computer Science & Engineering

- Construction Management

- Curriculum and Instruction

- Dental Hygiene

- Apparel Design

- Graphic Design

- Product Design

- Retail Merchandising

- Earth Sciences

- Electrical and Computer Engineering

- Environmental Sciences, Policy and Management

- Family Social Science

- Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology

- Food Science and Nutrition

- Geography, Environment and Society

- German, Nordic, Slavic & Dutch

- Health Services Management

- Horticultural Science

- Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication

- Industrial and Systems Engineering

- Information Technology Infrastructure

- Mathematics

- Mechanical Engineering

- Medical Laboratory Sciences

- Mortuary Science

- Organizational Leadership, Policy, and Development

- Political Science

- School of Architecture

- School of Kinesiology

- School of Public Health

- Spanish and Portuguese Studies

- Speech-Language-Hearing Sciences

- Theatre Arts & Dance

- Youth Studies

- New Enrollments for Departments and Programs

- Legacy Program for Continuing Units

- Writing in Your Course Context

- Syllabus Matters

- Mid-Semester Feedback Strategies

- Designing Effective Writing Assignments

- Writing Assignment Checklist

- Scaffolding and Sequencing Writing Assignments

- Informal, Exploratory Writing Activities

- 5-Minute Revision Workshops

- Reflective Memos

- Conducting In-Class Writing Activities: Notes on Procedures

- Now what? Responding to Informal Writing

- Teaching Writing with Quantitative Data

- Commenting on Student Writing

- Supporting Multilingual Learners

- Teaching with Effective Models of Writing

- Peer Response Protocols and Procedures

- Using Reflective Writing to Deepen Student Learning

- Conferencing with Student Writers

- Designing Inclusive Writing Assigments

- Addressing a Range of Writing Abilities in Your Courses

- Effective Grading Strategies

- Designing and Using Rubrics

- Running a Grade-Norming Session

- Working with Teaching Assistants

- Managing the Paper Load

- Teaching Writing with Sources

- Preventing Plagiarism

- Grammar Matters

- What is ChatGPT and how does it work?

- Incorporating ChatGPT into Classes with Writing Assignments: Policies, Syllabus Statements, and Recommendations

- Restricting ChatGPT Use in Classes with Writing Assignments: Policies, Syllabus Statements, and Recommendations

- What do we mean by "writing"?

- How can I teach writing effectively in an online course?

- What are the attributes of a "writing-intensive" course at the University of Minnesota?

- How can I talk with students about the use of artificial intelligence tools in their writing?

- How can I support inclusive participation on team-based writing projects?

- How can I design and assess reflective writing assignments?

- How can I use prewritten comments to give timely and thorough feedback on student writing?

- How can I use online discussion forums to support and engage students?

- How can I use and integrate the university libraries and academic librarians to support writing in my courses?

- How can I support students during the writing process?

- How can I use writing to help students develop self-regulated learning habits?

- Submit your own question

- Short Course: Teaching with Writing Online

- Five-Day Faculty Seminar

- Past Summer Hunker Participants

- Resources for Scholarly Writers

- Consultation Request

- Faculty Writing Groups

- Further Writing Resources

Your browser is not supported

Sorry but it looks as if your browser is out of date. To get the best experience using our site we recommend that you upgrade or switch browsers.

Find a solution

- Skip to main content

- Skip to navigation

- Back to parent navigation item

- Collections

- Sustainability in chemistry

- Simple rules

- Teacher well-being hub

- Women in chemistry

- Global science

- Escape room activities

- Decolonising chemistry teaching

- Teaching science skills

- Get the print issue

- RSC Education

- More navigation items

Writing effective questions for formative assessment

- No comments

Taking this approach will get your students thinking about how they can improve

Source: © Andrea Ebert/Ikon Images

It’s more than doing formative assessment, it’s about ‘being’ formative

I first became interested in the importance of classroom culture to successfully implement formative assessment when I was doing my doctorate in education. So, I want to introduce how to write and use questions more formatively so that they inform teaching and learning.

For me, it’s more than ‘doing’ formative assessment, it’s about ‘being’ formative, by creating a formative culture in your classroom. Formative values underpin everything that is done and said by teachers and learners in the formative classroom, although in real classrooms there is a blend of summative and formative approaches.

| Summative values | Formative values |

|---|---|

| Assessments are given to learners. | Assessments are done with learners. |

| Assessments, tasks and activities focus on outcomes. | Assessments, tasks and activities focus on processes |

| Language in the classroom focuses on exam topics, grades and performance. | Language in the classroom focuses on self-improvement, problem-solving skills and self-regulation. |

| Teachers and learners assess progress through test results. | Teachers and learners assess progress through knowledge and conceptual gain. |

The benefits of formative assessment have been seen in classrooms globally over the past two decades. In particular, formative assessment has highlighted the power of effective feedback, led to improvements in our understanding of how feedback can affect motivation, and helped to harness independence in learners through the development of self-regulation .

Download this

An audit to help you develop your formative practice as MS Word or pdf . Answer the questions to work out which practices you use and which you would like to develop.

Download all

An audit to help you develop your formative practice from the Education in Chemistry website: rsc.li/2DVRFef

Different teachers have different values with regard to assessment based on their personal pedagogy and the culture of the school in which they work. So it is useful to reflect upon your values, decide what you want to change and then make those changes in your practice. Here are three examples of formative practices in the use of written questions.

Writing closed questions

Closed questions, often in the form of knowledge tests, are a common approach to assess how well learners know a particular topic. These tests are often written as a list of recall questions that require short one- or two-word answers. In this summative approach, questions need to be closed and unambiguous. For example, what is the chemical symbol for chlorine?

However, these questions can be used more formatively if these become a resource rather than a test. Learners take ownership of the process by self-testing until they feel confident before a summative test takes place.

In a formative culture, you can use questions to support self-regulation. When setting a learning activity — learn the symbols for the first 20 elements — also ask the students ‘how’ they might achieve this. For example, the question could be ‘How will you make sure that you have really remembered the first 20 elements?’ There could be a discussion about which strategies students might try: ‘look, cover, write’ method, regular retesting, mixing up the order, or making a game, such as ‘pairs’ with cards of the names and symbols.

A formative approach focuses on the self-regulation principles of planning, monitoring and evaluating. It also promotes effective ways to learn, such as retrieval practice .

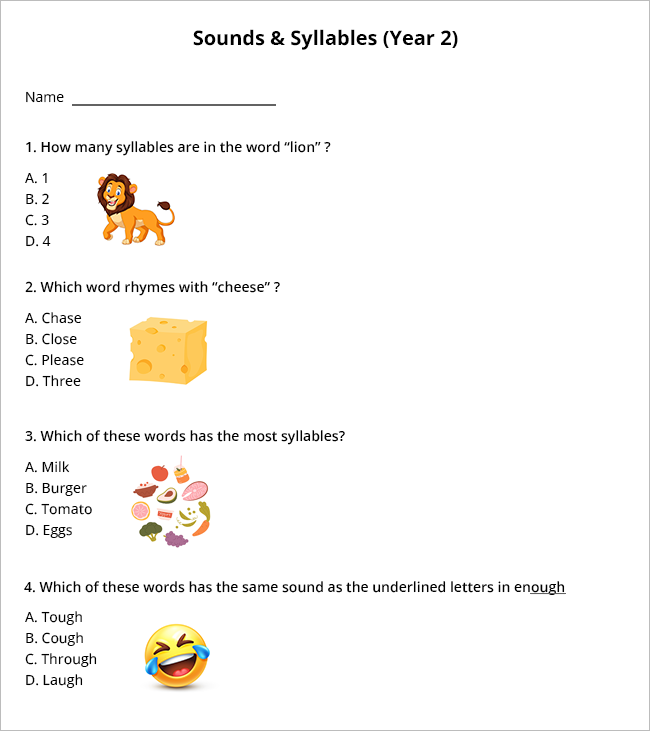

Writing diagnostic questions

Diagnostic questions are intended to be used formatively; they ask a question that is often supported by a choice of answers. Depending on the choice made by a learner, a judgment and intervention can be made. Carefully construct your diagnostic questions to ascertain what a learner knows about a particular concept. The questions can take several forms:

- Multiple choice questions – these are quick to answer and mark.

- Concept cartoons – in which a problem is given alongside three or four plausible answers.

- Pinch point multiple choice questions – whereby each answer leads to a specific intervention.

These questions can be difficult to write and often take a lot of research, trials and modifications to get right.

Using diagnostic questions as a summative test is possible, but it rather defeats the object. The follow-up from diagnostic questions focuses on the intervention and the learning. In a formative culture, teachers are more likely to explain the purpose of the activity. For example, a typical introduction to an activity might be: ‘This activity is to help you find out what you know and what you need to do more work on. Once you have done the task, based on the results, you can decide which improvement activity to do. At the end of the lesson, I want you to be able to tell me how you improved and what you did to make those improvements in your learning.’

This approach gives the learners some ownership over how they will address areas for improvement, values improvement by giving it time in the lesson, and emphasises what has been learned and how it has been learned (the process of learning).

Writing open-ended questions

Open questions are written to deliberately invite extended, thoughtful, detailed answers. They encourage learners to identify what they know, what they need to improve, and how to find out and learn deficits in knowledge and understanding.

Open questions, such as ‘What happens when a candle burns?’, often have supporting guidance like ‘Explain the physical and chemical processes that occur when a candle burns’ or a rubric to support the task. Examples of open-ended questions include the use of ‘grade-ladder tasks’ or threshold concept mastery tasks .

The structure of the lesson is often crucial to encourage a formative approach. The first part of the lesson is spent drafting the answer, a middle part reflecting on how to improve and the final part making those improvements. Yet, as with all teaching resources, it’s not what you do, it’s the way that you do it.

Developing a formative culture audit

More Andy Chandler-Grevatt

Reviewing the ECF

Establish good learning behaviours in the science lab

Get support from … ASE

- Developing teaching practice

- Secondary education

Related articles

Classroom assessment skills: 6 ways to develop your assessment literacy

2021-03-16T06:43:00Z By Andy Chandler-Grevatt

Master this essential skill and develop a mental map of your subject in three easy steps

5 tips for approaching formative assessment

2021-02-18T09:43:00Z By David Read

Use these research-informed teaching tips to better uncover your classes’ core chemical thinking

6 ways to develop your assessment skills

2021-02-08T09:24:00Z By Andy Chandler-Grevatt

Master the essentials of assessment to maximise your students’ learning

No comments yet

Only registered users can comment on this article., more feature.

Enhance students’ learning and development with digital resources

2024-06-17T05:02:00Z By David Paterson

Tips and a model to improve learners’ understanding and develop vital skills using digital learning

Getting the most out of the UK Chemistry Olympiad

2024-06-05T07:00:00Z

It’s the competition with something for every learner and teacher. Discover the benefits of participation here

Your guide to the UK Chemistry Olympiad

2024-06-05T07:00:00Z By Nina Notman

Discover how your school can easily participate in the leading annual chemistry competition for secondary school learners

- Contributors

- Print issue

- Email alerts

Site powered by Webvision Cloud

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Get our FREE Classroom Seating Charts 🪑

25 Formative Assessment Options Your Students Will Actually Enjoy

Get them excited to show you what they know!

Formative assessment is the piece of the teaching puzzle that allows us to quickly (and hopefully, accurately) gauge how well our students are understanding the material we’ve taught. From there, we make the important decisions about where our lesson will go next. Do we need to reteach, or are our students ready to progress? Do some students need additional practice? And which students need to be pushed to achieve the next level?

The best formative assessments will not only answer these questions but will also engage students in their own learning. With that in mind, here are 25 formative assessment techniques that will have your students looking forward to showing you what they know.

1. Doodle Notes

Have students doodle/draw a pic of their understanding instead of writing it. Studies have shown it has numerous beneficial effects on student learning.

2. Same Idea, New Situation

Ask your students to apply the concepts they’ve learned to a completely different situation. For example, students could apply the steps of the scientific method to figuring out how to beat an opposing soccer team. They observe data (the other team’s plays), form theories (they always rely on two main players), test theories while collecting more data (block those players and see what happens), and draw conclusions (see if that worked).

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

3. Tripwire

Tripwires are things that catch people off guard and mess them up. Ask your students to list what they believe are the three misunderstandings about the topic that are most likely to mess up a peer. By asking students to think about the key understandings from this angle, we can get an excellent view of how well they comprehend the topic.

4. Two Truths and a Lie

No longer just a get-to-know-you game or icebreaker, this well-known activity also makes a great formative assessment. Ask students to list two things that are true or accurate about the learning and one idea that sounds like it might be accurate, but isn’t. You’ll be able to assess each student’s understanding when they turn in their responses, and going over them with your class the following day makes an excellent review activity.

5. Popsicle Sticks

Formative assessment doesn’t need to be complicated or time-consuming to be meaningful and engaging. Have each student put their name on a popsicle stick in a jar or box on your desk. Let them know you’ll be pulling popsicle sticks to see who will be answering questions about the lesson. Knowing their name could be pulled makes students who might let peers do the talking focus on the learning. It dispels notions of favoritism and identifies learning gaps. And, most importantly, provides real-time feedback teachers can use in their lesson planning.

6. Explain it to a Famous Person

Ask the student to explain the day’s lesson to someone famous in an analogy that would make sense to that person. For example, the Revolutionary War was fought between the colonies and Great Britain. The colonies wanted to be independent and, after winning the war, renamed themselves the United States of America, just like when Prince left his record label and had to change his name to an unpronounceable symbol in order to break contractual obligations (I’m dating myself with this example, aren’t I?).

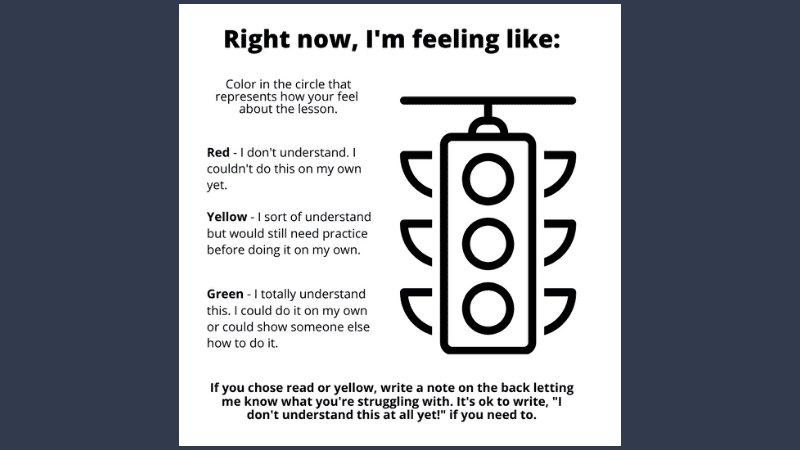

7. Traffic Light

Printing on post-it notes is actually pretty simple and fun! Slap a clip-art picture of a traffic light on there and you have a perfect formative assessment tool that students can complete when time is short at the end of class.

8. 30-Second Share

Challenge students to explain what the lesson they learned was all about to a peer, a small group, or the entire class in 30 seconds. At first, you might want to start at 15-seconds and build their stamina. But by encouraging students to explain everything they can for a set and relatively short amount of time, you’ll be building their confidence and public speaking skills at the same time as you get a good grasp on how much they’ve remembered about the lesson.

9. Venn Diagrams

An oldie but a goodie. Have your student compare the topic you just introduced to a tangential topic you taught in the past. This way, you’re getting a formative assessment on how well they understand the new topic and they’re getting a review of an older topic as well!

10. Poll Them

Polls are a great way to quickly assess student understanding. You can do this in person, or you can use apps like Poll Everywhere , Socrative , or Mentimeter to make free polls students can answer using their phones or computers.

11. S.O.S. Summaries

A great, quick formative assessment idea that can be used at any point throughout a lesson is the S.O.S. summary. The teacher presents the students with a statement (S). Then, asks the students to give their opinion (O) about the statement. Finally, the students are asked to support (S) their opinion with evidence from the lesson. For example, a teacher might say to the students, “Complete an S.O.S. on this statement: The Industrial Revolution produced only positive effects on society.”

S.O.S. can be used at the start of a lesson to assess prior knowledge or at the end of a unit or lesson to determine if students’ opinions have changed or if their support has grown stronger with the new information they’ve learned.

12. FOUR-Corners

This activity can be used with questions or opinions. Before asking the question/making the statement, establish each corner of the room as a different potential opinion or answer. After giving the prompt, each student goes to the corner that best represents their answer. Based on classroom discussion, students can then move from corner to corner, adjusting their answer or opinion.

13. Jigsaw Learning

Perfect when teaching complicated subjects or topics with many different parts. In this formative assessment, teachers break a large body of information into smaller sections. Each section is then assigned to a different small group. That small group is in charge of learning about their section and becoming the class experts. Then, one by one, each section teaches the others about their part of the whole. As the teacher listens to each section being taught, they can use the lesson as a method of formative assessment.

14. Anonymous Pop-Quiz

All the formative assessment power of a pop-quiz with none of the unnecessary pressure or embarrassment. To use this tool, simply quiz your students on the essential information you want to ensure they understand. Instruct each student NOT to put their name on their paper.

Once the assessment is complete, redistribute the quizzes in a way that ensures no one knows whose quiz they have in front of them. Have the students correct the quizzes and share out which answers most students got wrong and which answers everyone seemed to understand the most. You’ll know right away how well the class as a whole understands the topic without embarrassing any students individually.

15. One-Minute Write-Up

At the end of a lesson, give students one minute to write as much as they can about what they learned through the lesson or unit. If needed, provide some guiding questions to get them started.

- What was the most important learning from today, and why?

- Did anything surprise you? If so, what?

- What was the most confusing part of the lesson, and why?

- What is something that will likely appear on a test or quiz, and why?

Challenge them to write as much as they can and to write for all of the 60-seconds. To make it a bit more engaging, consider letting students do this with a partner.

16. EdPuzzle

Students love to watch videos and, because of this, we end up showing a lot of short video clips. While they’re engaging, it’s often tough to determine if our students are getting the information we hoped they would get out of watching them. EdPuzzle solves this problem. The free app allows you to link to a video and add questions that stop the video at times you determine. So you can show your students the video of the Dust Bowl, but stop at various points to ask them what they think life might have been like during this time. You can ask them to make comparisons between what they watch and the characters they’re reading about in class. All of this information is then available for you to view and use for formative assessment.

17. Historical Post Cards

Ask students to take on the role of one historical figure you’ve been learning about in class. Have them write a postcard/email/tweet (as long as it’s short) to another historical figure discussing and describing a political event.

18. 3x Summaries

Have students write a 75-100 word summary of a lesson independently. Then, in pairs, have them rewrite it using only 35-50 words. Finally, have them work with a small group to rewrite it one last time. This time, they may use only 10-15 words. Discuss what different groups decided was the most essential information and why they chose to omit certain information. The conversation about what they left out is just as useful as seeing what they left in.

19. Roses and Thorns

Ask students to write or share out two things they really liked/understood about a topic (the roses) and something they didn’t like/didn’t understand (the thorn).

20. Thumbs Up, Down, or in the Middle

Sometimes things stick around because they just work. Asking students to give you a thumbs up if they understand, thumbs down if they don’t, or thumbs somewhere in the middle if they are so-so about it, is probably one of the fastest formative assessments around. It’s also very easy to keep track of if you’re the teacher standing in the front of the room. Just make sure that you follow up with the thumbs down or thumbs in the middle folks to help them with any confusion.

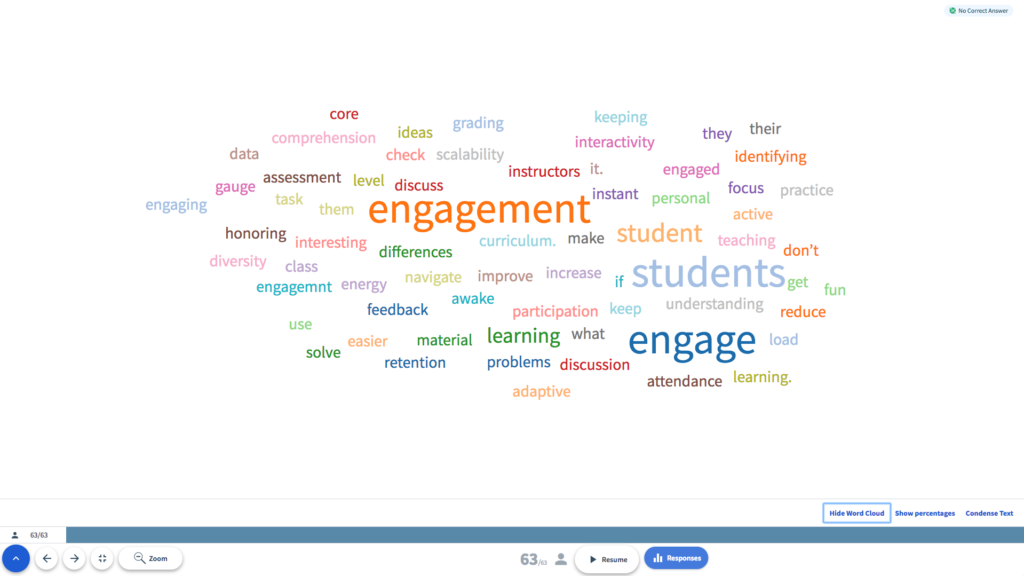

21. Word Clouds

Ask your students to provide you with the three most essential words or ideas from a lesson and plug them into a word cloud generator . You’ll quickly have an excellent formative assessment that shows you what they thought was most worthy of remembering. If it doesn’t line up with what you think was most important, you know what you need to reteach.

22. Curation

Ask students to gather a bunch of examples that correctly demonstrate the concept you taught. So if you’re studying rhetorical strategies, have students send you screenshots of ads that demonstrate them. Not only will you be able to tell immediately who understood the lesson and who didn’t, but you’ll also have a bunch of great examples and non-examples ready to go for those students who need additional practice.

23. Dry Erase Boards

Another time-tested method of formative assessment that teachers often overlook is individual dry erase boards. They really are an awesome and fast way to see where each student’s level of understanding is at any given point.

24. Think-Pair-Shares

Like so many teacher tools, this one can get stale if overused. But, if used as a method to encourage all students to find their voice and share their learning, it’s perfect for formative assessment. To ensure its effectiveness, ask a question of the class. Have every student write down their own answer. Pair students up with a classmate and give them time to share and discuss their answers. After pairs have had a chance to discuss, have them share out with a larger group or the class as a whole. Circulate, listening to groups who have students you know might be more likely to struggle with the current topic. Collect the papers for extra accountability.

25. Self-Directed

This one can intimidate some students at first, but it can be incredibly powerful to let students themselves choose how they want to demonstrate learning. You can support students by giving them managed choice, but let them decide if they want to show you they understood the essential parts of your lesson by drawing a picture, writing a paragraph, creating a pop quiz, or even writing song lyrics. This shows you’re putting them in charge of their own learning.

What’s your go-to method of formative assessment? Tell us in the comments.

Get more teaching tips and ideas when you sign up for our free newsletters .

You Might Also Like

25 Alternative Assessment Ideas

Test outside the box. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

- Professional learning

Teach. Learn. Grow.

Teach. learn. grow. the education blog.

27 easy formative assessment strategies for gathering evidence of student learning

- New Clothes

- Dos and Don’ts

- Three Common Misunderstandings

- Yes/No Chart

- Three Questions

- Explain What Matters

- Big Picture

- Venn Diagram

- Self-Directed Response

Combining these 10 with 10 others we’ve blogged about in the past gives teachers 20 great formative assessment strategies for checking on student learning. Be sure to click through to learn more about these formative assessment strategies.

- The Popsicle Stick

- The Exit Ticket

- The Whiteboard

- Think-Pair-Share

- Two Stars and a Wish

- Carousel Brainstorming

- Basketball Discussions

Want more? Here are seven more strategies you can use to elicit evidence of student learning.

- Entrance Tickets. We’ve blogged about and explained the Exit Ticket, so why not have an Entrance Ticket? Here, the teacher asks a question at the start of a lesson, and students write their responses on index cards or strips of paper. Answers are used to assess initial understanding of something to be discussed in that day’s lesson or as a short summary of understanding of the previous day’s lesson. The teacher designs the lesson around the fact that information on student learning will be coming in at the start of the lesson and can be used to improve the teaching and learning in that lesson. Be sure to write the question so it is easily interpreted and analyzed, allows time for you and/or the students to analyze the responses, and leaves space for you to adjust the lesson, if needed.

- Keep the Question Going. With this formative assessment strategy, you’ll ask one student a question and then ask another student if that answer seems reasonable or correct. Then, ask a third student for an explanation of why there is an agreement or not. This helps keep all the students engaged because they must be prepared to either agree or disagree with the answers given and provide explanations.

- 30-Second Share. With this strategy, students take a turn to report something learned in a lesson for up to 30 seconds each. Connections to the learning targets or success criteria are what you’ll be looking for in the language used by the student. Make this a routine at the end of a lesson so all students have the opportunity to participate, share insights, and clarify what was learned.

- Parking Lot. This is an underused strategy for students and one that can surface questions before learning, as well as during and after. This tool also offers an anonymous place for questions that may be directly related to the content or tangential to the current topic and provide insight into student thinking. Simply save a spot on your whiteboard to write down ideas or questions that aren’t completely relevant in the moment but should be revisited later.

- One-Minute Paper. This might be considered a type of exit ticket as it is typically done near the end of the day. Ask your students, either individually or with a partner, to respond in writing to a single prompt. Typical prompts include:

- Most important learning from the day and why

- Most surprising concept and why

- Most confusing topic and why

- Something I think might appear on a test or quiz and why

- 3-2-1. At the end of the learning, this strategy provides students a way to summarize or even question what they just learned. Three prompts are provided for students to respond to:

- 3 things you didn’t know before

- 2 things that surprised you about the topic

- 1 thing you want to start doing with what you’ve learned

- Assessment Reflection. This strategy is a post-assessment reflection completed individually first and then shared in a small group. After an assessment, the teacher provides a list of questions so learners can reflect on their assessment experience. During group discussion, ideas are collected as new information to support students to better prepare for and engage in future assessments. Consider the following or similar questions. You might also use strategies such as Plus, Minus, Interesting, or Plus/Delta.

- How engaged were you with this assessment? Why?

- What did you feel most confident about? Why?

- What did you do that led to your success or confidence?

- What was the most difficult part of this assessment? Why?

- What would you do differently next time?

- What was the most confusing? Why?

- What do you know about the topic that the assessment didn’t allow you to show?

All 27 of these formative assessment strategies are simple to administer and free or inexpensive to use. They’ll provide you with the evidence of student learning you need to make lesson plan adjustments and keep learning on target and moving forward. They’ll also give your students valuable information so they can adjust their learning tactics and know where to focus their energies.

If you’re not quite sure where to get started, the following discussion questions can help.

Questions for teachers

- How do you use formative assessment data to inform instructional decisions?

- How can formative assessment strategies foster a learning environment of collaboration and engagement?

- How do formative assessment strategies elicit evidence of student learning?

- What is one strategy you could try tomorrow and why?

Questions for leaders

- How do you use formative assessment data to drive school-wide instructional academic decisions?

- How can you model formative assessment strategies in staff meetings, PLCs, and meetings with teachers?

- What are three formative assessment strategies you could bring to your teachers and staff? Why do you feel these would be most effective at your school?

Get more formative assessment tips and tricks in our e-book “Making it work: How formative assessment can supercharge your practice.”

Recommended for you

Norm- vs. criterion-referenced in assessment: What you need to know

MAP Reading Fluency with Coach provides targeted interventions grounded in the science of reading

K–12 data leadership: Be the change for your school community

Making it work: How formative assessment can supercharge your practice

Formative assessment isn’t new. But as our education system changes, our approaches to any instructional strategy must evolve. Learn how to put formative assessment to work in your classroom.

View the eBook

STAY CURRENT by subscribing to our newsletter

You are now signed up to receive our newsletter containing the latest news, blogs, and resources from nwea..

Formative assessments: the ultimate guide for teachers

- Categories Blog

- Date February 14, 2024

K-12 education is a construction process where students’ skills and knowledge are gradually built up, with every preceding “block” essential to keep on building.

As a teacher, it’s your job to ensure that your students have the core knowledge they need to keep advancing through their education. You need a daily understanding of their current skills and knowledge so that you can accurately gauge their progression, and decide what to teach them next.

One of the most effective, proven ways to do this is with formative assessments (OECD, 2008). 1 They’re a crucial tool in your teaching kit, helping you to provide quality education to students.

Table of contents

- What are formative assessments?

- Evidence that formative assessment works

- Formative assessment examples / types

- Formative assessment strategies for your school and classroom

1. What are formative assessments?

Formative assessments are regular low-stakes tests that help you gauge students’ understanding. They are “dipsticks” where you can quickly check learning as you might quickly check the oil in your car, allowing you to adapt your teaching and fill knowledge gaps while learning is still taking place.

Quizzes are a common example of formative assessments. They’re quick to create, complete, and mark, and give you a good impression of students’ understanding of the content and their progress for the unit. You can see which questions and topics they are struggling with, re-teach them, and then re-test – a rapid feedback and improvement cycle that boosts student outcomes and moves them along their learning journeys.

You can see how this differs from summative assessments like end-of-year exams. These are one-off tests used to evaluate student understanding after learning has finished, with no opportunity to improve. Their purpose is to grade. But with formative assessments, getting the right answers isn’t important because that isn’t the objective. Instead, the purpose is to provide you with continuous, fast “readings” of student progress which you use to adapt your teaching and advance their learning. Summative assessments are to grade, and formative assessments are to direct .

As you can imagine, this sets entirely different tones for the two types of assessment. Summative tests can be high-stakes with real consequences that shape students’ future opportunities. This makes them understandably anxious, which can significantly affect their performance (Embse et al., 2018). 2 Formative assessments, on the other hand, are low-stakes, light-touch tests that are (ideally) designed to be fun and engaging, and to boost learning outcomes (OECD, 2008). 5 Formative assessments help to improve summative assessment scores/grades (and more importantly, their education), but this doesn’t work the other way around.

To make our position clear: both types of assessment have an important place in education. They just have different purposes and effects on students. If you’d like a more detailed comparison of these two types of assessment, please check out our article here .

How formative assessments help your teaching

“Formative assessment – while not a “silver bullet” that can solve all educational challenges – offers a powerful means for meeting goals for high-performance, high-equity of student outcomes, and for providing students with knowledge and skills for lifelong learning.” 1

– OECD

In essence, formative assessments help you answer three key questions:

- Are students learning what they need to learn?

- Are students learning at a steady pace?

- What should be taught next?

The answers to these questions form an objective appraisal of your current teaching strategies and lesson plans, providing clues on what needs to change. This may include the following and more:

- Change of content – formative assessments reveal student understanding, which includes any learning gaps or misconceptions they may have. With this information, you can adjust the content being taught to ensure they are learning what they need.

- Refine learning intentions – when you have a strong understanding of your students’ knowledge and skills, you’re able to write more precise learning intentions in your lesson plans, and by extension, better plans overall that accurately address students’ needs.

- Group students based on ability – formative assessments are usually given to entire classes, which reveals students’ both individually, and as a whole. If assessment results reveal distinct groupings of students based on their knowledge and skill, and you have the capacity to group them in your class and set unique work, that’s a much more inclusive way to teach and likely to result in better learning outcomes. More broadly, this information also helps you form separate support classes or Gifted and Talented classes.

- Change frequency of assessment – if you’ve previously identified knowledge gaps, you’ll want to re-assess after learning to ensure they’re filled. While formative assessment should be a regular occurrence in your class, the frequency should change depending on the results and other feedback you get from students.

Formative assessments in action – a quick example

“Assessment is the bridge between teaching and learning. It’s only by assessment that you know what has been taught, has been learned.” 3

– Dylan Wiliam, formative assessment expert

To give you an example of formative assessments in action, let’s say you’re a Year 8 Science teacher starting a new term with students, and before proceeding with the content assigned to this term, you want to check their understanding to ensure they’ve mastered the prerequisite content, allowing you to correctly build on their knowledge.

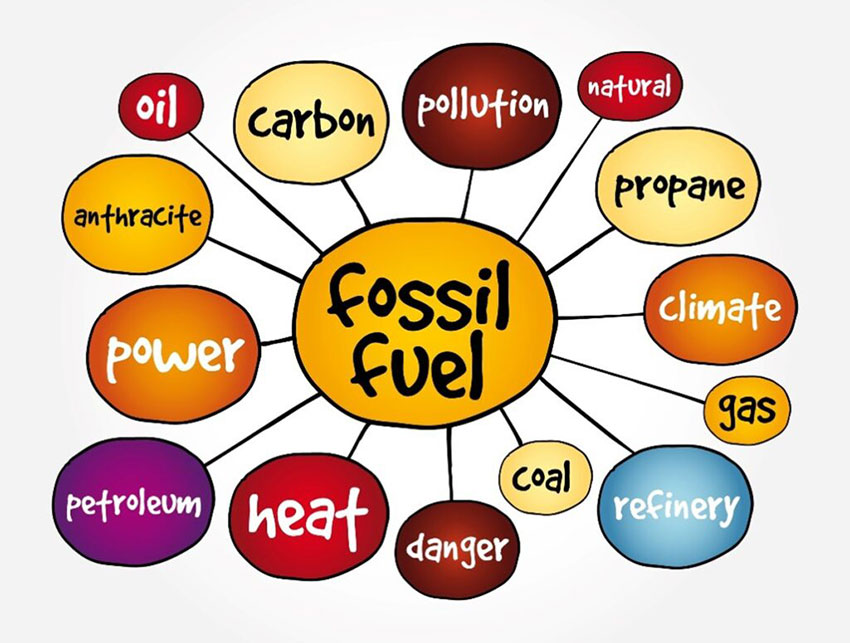

As part of this term, students are extending their knowledge of biological sciences. So you ask them to take five minutes to create individual mind maps of everything they remember about cells – a brain dump of the content they have already been taught last term. Walking around the class, you can see maps that contain organelles, membranes, nuclei, and even little drawings of cell structures. Some students have filled their A4 sheet and others have barely touched it (mental note added). But overall, your students have covered the core concepts they learned last year.

To validate this information, you’d like them to elaborate on their mind maps to ensure they actually understand (rather than just remember) the concepts, so you write a few of the key ideas on the board and ask who would like to explain it. They seem to have a good grasp of membranes and nuclei, but even with plenty of hints, nobody can accurately describe what organelles do, or how the cells of plants and animals differ. You’ve identified two clear topics that need some refreshing, which you can either teach immediately or add to your next lesson plan.

These formative assessments may have taken no longer than 10 minutes. Of course, there needs to be a good balance between assessment and instruction, but that’s the beauty of formative assessments: they are quick and sharp and provide you with objective, real-world data that effectively directs your teaching. By incorporating formative assessments into your day-to-day teaching, you have vital feedback on student learning which you can use to identify and fill their knowledge gaps, build on their knowledge, and set them up for success.

Formative assessments help students become self-learners

Formative assessments have another effect on students that can improve their education and lives immeasurably: they help them become empowered self-learners (Clark, 2012). 3

This happens for two reasons:

They learn self-evaluation techniques

Many formative assessments have processes in which students assess their own work or the work of their peers. Rubrics are a good example. You can give students a marking rubric that allows them to assess their classmates’ abilities at reading aloud, as per below:

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Very quiet and almost impossible to hear | Quiet, but can just about hear | Ideal volume, everyone can hear clearly |

|

| Stopping and starting every few seconds | Occasional stops and starts | Consistent, good speed with few stops and starts |

|

| Lots of mumbling, difficult to understand | Most words pronounced clearly, but some mumbling here and there | Great pronunciation, very clearly understood |

“By learning how to evaluate their own work, students develop the crucial meta-cognitive skills they need to progress by themselves.”

By using this rubric as a guide, they can score their classmates on volume, fluency, and clarity, and in the process, they also learn how to assess their own skills and pinpoint areas of weakness.

Informal debates are another example. You can create small groups of students and ask them to debate an issue in which they express their opinions, back them up with evidence, and listen to why their classmates agree or disagree. The conversations help them discover potential misconceptions or logical flaws, again teaching them (through modelling) how to evaluate such things by themselves.

By learning how to evaluate their own work, students develop the crucial meta-cognitive skills they need to progress by themselves. It’s giving them the proverbial fishing rod instead of a fish. They learn how to reflect, critique, review, and mark their own work, giving them a firm grip on their own learning and accelerating them to speeds far beyond what teachers can achieve by themselves. This leads to greater self-efficacy (Panadero et all., 2017) 4 and success.

They’re interactive and social

Formative assessments are highly varied, interactive tasks that students engage with during class. For most students, because the assessments are hands-on activities that require their attention, this makes them more interesting than standard instruction from the teacher. Students often become enthusiastically engaged in their learning, which creates a sense of agency and responsibility for their education. When combined with learning goals, this can be a powerful tool for improving outcomes.

Similarly, formative assessments can be co-operative social activities where students are encouraged to interact with their classmates and teachers. They might be having conversations with each other, validating their knowledge before and after learning, self-assessing using proven techniques, and many other activities (see our full list of assessment examples below) in which they are active and involved. As socially-driven creatures, this can turn your students’ learning from dull chores into genuinely fun experiences where they build friendships along the way.

2. Evidence that formative assessment works

“Teaching which incorporates formative assessment has helped to raise levels of student achievement, and has better enabled teachers to meet the needs of increasingly diverse student populations, helping to close gaps in equity of student outcomes.” 1

Formative assessments have been studied extensively, and show sweeping improvements for learning outcomes (OECD, 2008). 1

A comprehensive report on formative assessment by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), backed up by numerous studies, found the practice to be one of the most important interventions for promoting high [student] performance ever studied (OECD, 2008). 1 It’s the equivalent of taking students’ scores in an average performing country and lifting them into the top five best performing countries (Beaton et al., 1996, Black and Wiliam, 1998) 5,6 .

The OECD report shows that formative assessments:

- Make education more equitable . They lift the performance of every single student, including those who are underachieving.

- Improve school attendance . Formative assessments tend to be fun and engaging for students, which makes school much more enjoyable and reduces absence rates.

- Help students retain what they’ve learned. Assessments tap into the “testing effect” – a phenomenon in which the act of testing also boosts learning. Trying to recall information from memory is a highly effective way to learn (Brown et al., 2014). 9

- Help students become self-learners . They are more involved and engaged in the learning process itself, discovering the mechanics behind learning and self-evaluation and how they can do it themselves.

- Help to clarify misconceptions. These can be immediately corrected during learning, before they are consolidated into long-term memories during sleep (Klinzing, Niethard and Born, 2019). 11

Aside from the OECD report, there are numerous studies where formative assessment has proven its worth. A 2021 meta-analysis of 32 studies found that formative assessments boosted learning outcomes considerably (Karaman, 2021). 11 For the core foundational skill of Writing, another meta-analysis of formative assessment experiments found feedback to be a crucial part of the process. When teachers and peers gave feedback, and students self-evaluated their own work, writing quality was enhanced (Graham et al., 2015). 7

Another study found formative assessment to have a positive influence on literacy as well as maths and the arts. Helping students to self-assess provided one of the biggest benefits, as did providing written feedback on quizzes (Lee et al., 2020). 8 Feedback has proven to be a crucial part of effective formative assessment, and we cover this in more detail below. For Science, high school biology teachers who completed a professional development program on formative assessment saw their abilities increase for key areas such as interpreting student ideas, eliciting questions and providing feedback (Furtak, et all., 2016). 7

Finally, in a random sample of 22 Swedish Year 4 Mathematics teachers, researchers asked them to participate in a professional development program on formative assessment. After implementing their knowledge in their respective classes, their students significantly outperformed others (Andersson, Palm, 2016). 10

We could go on. There’s so much evidence of the efficacy of formative assessment. It’s amazing to think that such drastic improvements can be made by introducing effective formative assessments into your classrooms (we talk more about effective strategies below).

3. Formative assessment examples / types and how they work

Formative assessments are extremely diverse. They range from generic to subject/content-specific, allowing you to assess knowledge and skills in a variety of ways, and cover the full breadth of K-12. You can pick and choose which formative assessments suit your students based on their age and the covered content.

Their variety and spontaneity can make learning much more fun for students of all ages. These are some of the more common formative assessment examples you’ll find in schools across the world.

Age group: all

Quizzes are one of the most popular types of formative assessment, and for good reason: they’re fun, quick to create and mark, and give you a great indication of students’ general knowledge, learning gaps and possible misconceptions for a topic. They can be given as:

- Diagnostic pre-tests before starting a new unit

- Mid-unit checkups to determine whether learning is going according to plan

- Evaluative tests that check learning before the next unit starts

- Start or end of lesson check-ups to quickly assess learning

Quizzes typically contain multiple-choice questions , which make them nice and quick to mark. But they can take other forms if needed. You can also incorporate directive feedback into each quiz’s results to show students what they might do to improve.

Discussion boards

With discussion boards, students write what they know about a topic on the whiteboard. This could be as a mind map, graffiti wall, or another format, with students writing short words or phrases, full sentences, or even drawing pictures. It’s a brain-dump of sorts that helps you understand students’ depth of knowledge for a topic, and any potential learning gaps or misconceptions you need to address.

Brain dumps are the same as discussion boards but are completed on paper or screens, either individually or in small groups. Students write everything they know about a topic in the format they prefer, which gives you an idea of their knowledge for the topic.

Traffic light system

With the traffic light system, each student is given three coloured cards – one red, one orange and one green – which they need to hold up in response to a statement. Red is disagree, orange is unsure, and green is agree. You might ask them whether 10 times 10 is 200, whether day and night is created by the moon, or whether the word “running” is a verb.

When students hold their cards up, you get a visual gauge of how many students answered correctly. It’s another super-quick, fun formative assessment for younger students.

Questions / surveys

These are the simplest formative test of all: you ask questions to the class and assess their answers on the spot. They’re a staple of teaching around the world because they give you an ultra-fast idea of what your students know about the content already taught, so that you can refresh their memories if needed. You’ll be able to gauge their knowledge from the numbers of hands raised and the quality of answers (keeping in mind the general shyness of that particular class).

Rubrics / self-evaluation

Age group: Years 3 to 10

When students learn how to assess their own work, they’re on the road to becoming self-learners who can develop a fully-fledged love of learning. Rubrics are a formative assessment that helps them on this path. They’re a simple marking criteria that students can apply to their own (or their classmates’) work to judge their performance, and what improvements they might need to make.

As already touched on previously, an example is the reading rubric shown below. Students can listen to their classmates read aloud, give them a score for each skill, and then discuss why they gave them afterwards. The rubric is one of many tools that students can use to self-evaluate and become enthusiastic independent learners.

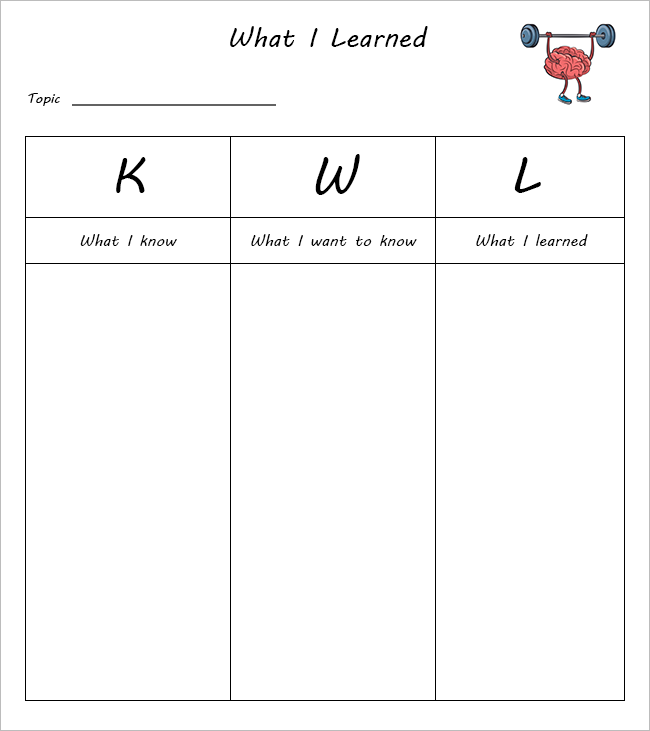

KWL charts are a formative assessment that prepare your students for what they’re going to learn, get them invested in their own learning, and help them evaluate whether learning was successful.

Three columns are drawn on the board in class, from left to right:

- What I know

- What I want to know

- What I learned

For the content being taught in today’s class, students are invited to write about what they know about it, and what they want to know about it. They complete the “what I learned” third column at the end of class, showing them whether they achieved their desires/objectives. This is another simple, effective way for students to assess their own learning.

You can include an additional section if you wish – how will you learn it (which makes it KWHL). This encourages students to think about how to research and discover the information.

Think-Pair-Share

Age group: Years 1 to 9

With Think-Pair-Share, students write down their responses to a question and then discuss their answers with a partner. You walk around the room and listen to their discussions, to gauge their level of understanding of the topic. Finally, they share their answers with the class, which encourages them to reflect on the accuracy and logic of their own.

See, Think, Wonder

Age group: Years 1 to 5

See, Think, Wonder is a formative assessment that stimulates students’ curiosities and really gets them thinking about an image. They are given a photograph or picture and sheets with three columns that must be filled out:

- See – they describe what they see using descriptive language

- Think – they describe what they think is going on with the image

- Wonder – they write anything they’re wondering about the image

The task shows you the quality of their writing, their interpretation skills, their creativity, the accuracy of their observations, and more. Once done they can discuss their answers with students at their table, which encourages teamwork, or read them to the entire class.

Thumbs up or down

This is another quick and easy assessment that reveals general misconceptions. You offer a statement and ask them to give a thumbs up if they agree, and a thumbs down if they disagree. By judging the accuracy of their answers, you’ll know whether common misconceptions are present and resolve them if so.

For the statements, it can be a good idea to use any that your prior students have struggled with in the past.

Hot seat questioning

Hot seat questioning is an assessment that makes questions a little more fun. Anonymous questions are placed on a selection of seats, typically in front of class, and students are invited to select a seat, read the question aloud, and then try to answer. The rest of the class are encouraged to discuss the students’ answer and provide their own if appropriate.

The questions can vary in difficulty depending on the subject and year level. It can be an engaging, fun way to assess student learning and stimulate discussion.

Entry & exit slips

Age group: Years 1 to 6