- Mattress Education Mattress Sizes Mattress Types Choosing the Best Mattress Replacing a Mattress Caring for a Mattress Mattress Disposal Mattress Accessories Adjustable Beds Mattress Sizes Mattress Types Choosing the Best Mattress Replacing a Mattress Caring for a Mattress Mattress Disposal Mattress Accessories Adjustable Beds

- Better Sleep Sleep Positions Better Sleep Guide How to Sleep Better Tips for Surviving Daylight Saving Time The Ideal Bedroom Survey: Relationships & Sleep Children & Sleep Sleep Myths

- Resources Blog Research Press Releases

- Extras The Science of Sleep Stages of Sleep Sleep Disorders Sleep Safety Consequences of Poor Sleep Bedroom Evolution History of the Mattress

- December 12, 2018

Teens, Sleep and Homework Survey Results

Better sleep council research finds that too much homework can actually hurt teens' performance in school.

- Press Releases

ALEXANDRIA, Va. , Dec. 11, 2018 – According to new research from the Better Sleep Council (BSC) – the nonprofit consumer-education arm of the International Sleep Products Association – homework, rather than social pressure, is the number one cause of teenage stress, negatively affecting their sleep and ultimately impacting their academic performance.

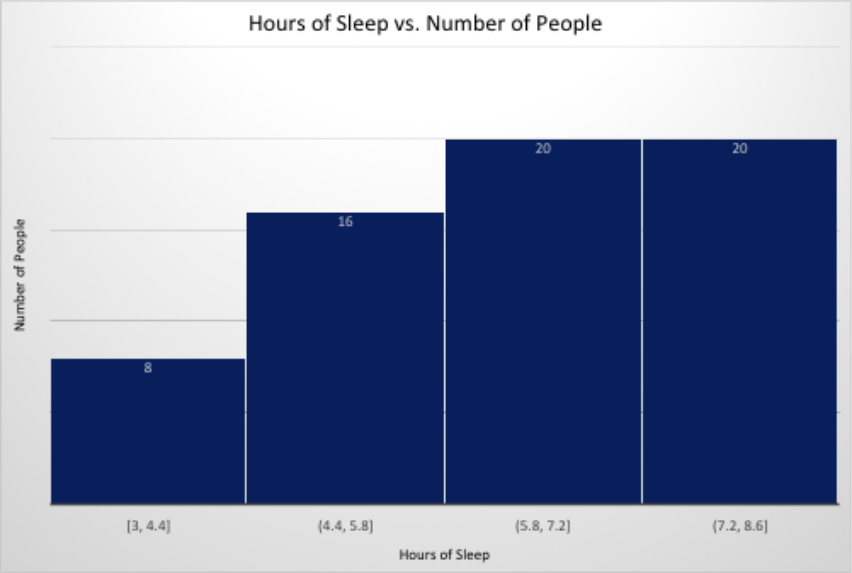

American teenagers said they spend 15+ hours a week on homework, and about one-third (34%) of all teens spend 20 or more hours a week. This is more than time spent at work, school clubs, social activities and sports. When asked what causes stress in their lives, about three-quarters of teens said grades/test scores (75%) and/or homework (74%) cause stress, more than self-esteem (51%), parental expectations (45%) and even bullying (15%). In fact, according to the American Psychological Association’s Stress in America™ Survey, during the school year, teenagers say they experience stress levels higher than those reported by adults.

Further, more than half (57%) of all teenagers surveyed do not feel they get enough sleep. Seventy-nine percent reported getting 7 hours of sleep or less on a typical school night, more than two-thirds (67%) say they only get 5 to 7 hours of sleep on a school night, and only about one in five teens is getting 8 hours of sleep or more. Based on the BSC’s findings, the more stressed teenagers feel, the more likely they are to get less sleep, go to bed later and wake up earlier. They are also more likely to have trouble going to sleep and staying asleep – more often than their less-stressed peers.

“We’re finding that teenagers are experiencing this cycle where they sacrifice their sleep to spend extra time on homework, which gives them more stress – but they don’t get better grades,” said Mary Helen Rogers , vice president of marketing and communications for the Better Sleep Council. “The BSC understands the impact sleep has on teenagers’ overall development, so we can help them reduce this stress through improved sleep habits.”

The BSC recommends that teens between the ages of 13-18 get 8-10 hours of sleep per night. For teens to get the sleep their bodies need for optimal school performance, they should consider the following tips:

- Establish a consistent bedtime routine . Just like they set time aside for homework, they should schedule at least 8 hours of sleep into their daily calendars. It may be challenging in the beginning, but it will help in the long run.

- Keep it quiet in the bedroom. It’s easier to sleep when there isn’t extra noise. Teens may even want to wear earplugs if their home is too noisy.

- Create a relaxing sleep environment. Make sure the bedroom is clutter-free, dark and conducive to great sleep. A cool bedroom, between 65 and 67 degrees , is ideal to help teens sleep.

- Cut back on screen time. Try cutting off screen time at least an hour before bed. The blue light emitted from electronics’ screens disturbs sleep.

- Examine their mattress. Since a mattress is an important component of a good night’s sleep, consider replacing it if it isn’t providing comfort and support, or hasn’t been changed in at least seven years.

Other takeaways on the relationship between homework, stress and sleep in teenagers include:

- Teens who feel more stress (89%) are more likely than less-stressed teens (65%) to say homework causes them stress in their lives.

- More than three-quarters (76%) of teens who feel more stress say they don’t feel they get enough sleep – which is significantly higher than teens who are not stressed, since only 42% of them feel they don’t get enough sleep.

- Teens who feel more stress (51%) are more likely than less-stressed teens (35%) to get to bed at 11 p.m. or later. Among these teens who are going to bed later, about 33% of them said they are waking up at 6:00 a.m. or earlier.

- Students who go to bed earlier and awaken earlier perform better academically than those who stay up late – even to do homework.

About the BSC The Better Sleep Council is the consumer-education arm of the International Sleep Products Association, the trade association for the mattress industry. With decades invested in improving sleep quality, the BSC educates consumers on the link between sleep and health, and the role of the sleep environment, primarily through www.bettersleep.org , partner support and consumer outreach.

Related Posts

The State of America’s Sleep: COVID-19 and Sleep

The state of america’s sleep: isolation and sleep, the state of america’s sleep.

ABOUT THE BETTER SLEEP COUNCIL

- Mattress Education

- Better Sleep

- Privacy Policy

- Confidentiality Statement

- Our Mission

Homework, Sleep, and the Student Brain

At some point, every parent wishes their high school aged student would go to bed earlier as well as find time to pursue their own passions -- or maybe even choose to relax. This thought reemerged as I reread Anna Quindlen's commencement speech, A Short Guide to a Happy Life. The central message of this address, never actually stated, was: "Get a life."

But what prevents students from "getting a life," especially between September and June? One answer is homework.

Favorable Working Conditions

As a history teacher at St. Andrew's Episcopal School and director of the Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning , I want to be clear that I both give and support the idea of homework. But homework, whether good or bad, takes time and often cuts into each student's sleep, family dinner, or freedom to follow passions outside of school. For too many students, homework is too often about compliance and "not losing points" rather than about learning.

Most schools have a philosophy about homework that is challenged by each parent's experience doing homework "back in the day." Parents' common misconception is that the teachers and schools giving more homework are more challenging and therefore better teachers and schools. This is a false assumption. The amount of homework your son or daughter does each night should not be a source of pride for the quality of a school. In fact, I would suggest a different metric when evaluating your child's homework. Are you able to stay up with your son or daughter until he or she finishes those assignments? If the answer is no, then too much homework is being assigned, and you both need more of the sleep that, according to Daniel T. Willingham , is crucial to memory consolidation.

I have often joked with my students, while teaching the Progressive Movement and rise of unions between the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, that they should consider striking because of how schools violate child labor laws. If school is each student's "job," then students are working hours usually assigned to Washington, DC lawyers (combing the hours of the school day, school-sponsored activities, and homework). This would certainly be a risky strategy for changing how schools and teachers think about homework, but it certainly would gain attention. (If any of my students are reading this, don't try it!)

So how can we change things?

The Scientific Approach

In the study "What Great Homework Looks Like" from the journal Think Differently and Deeply , which connects research in how the brain learns to the instructional practice of teachers, we see moderate advantages of no more than two hours of homework for high school students. For younger students, the correlation is even smaller. Homework does teach other important, non-cognitive skills such as time management, sustained attention, and rule following, but let us not mask that as learning the content and skills that most assignments are supposed to teach.

Homework can be a powerful learning tool -- if designed and assigned correctly. I say "learning," because good homework should be an independent moment for each student or groups of students through virtual collaboration. It should be challenging and engaging enough to allow for deliberate practice of essential content and skills, but not so hard that parents are asked to recall what they learned in high school. All that usually leads to is family stress.

But even when good homework is assigned, it is the student's approach that is critical. A scientific approach to tackling their homework can actually lead to deepened learning in less time. The biggest contributor to the length of a student's homework is task switching. Too often, students jump between their work on an assignment and the lure of social media. But I have found it hard to convince students of the cost associated with such task switching. Imagine a student writing an essay for AP English class or completing math proofs for their honors geometry class. In the middle of the work, their phone announces a new text message. This is a moment of truth for the student. Should they address that text before or after they finish their assignment?

Delayed Gratification

When a student chooses to check their text, respond and then possibly take an extended dive into social media, they lose a percentage of the learning that has already happened. As a result, when they return to the AP essay or honors geometry proof, they need to retrace their learning in order to catch up to where they were. This jump, between homework and social media, is actually extending the time a student spends on an assignment. My colleagues and I coach our students to see social media as a reward for finishing an assignment. Delaying gratification is an important non-cognitive skill and one that research has shown enhances life outcomes (see the Stanford Marshmallow Test ).

At my school, the goal is to reduce the barriers for each student to meet his or her peak potential without lowering the bar. Good, purposeful homework should be part of any student's learning journey. But it takes teachers to design better homework (which can include no homework at all on some nights), parents to not see hours of homework as a measure of school quality, and students to reflect on their current homework strategies while applying new, research-backed ones. Together, we can all get more sleep -- and that, research shows, is very good for all of our brains and for each student's learning.

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

The Impact of Sleep on Learning and Memory

By Kelly Cappello, B.A.

For many students, staying awake all night to study is common practice. According to Medical News Today , around 20 percent of students pull all-nighters at least once a month, and about 35 percent stay up past three in the morning once or more weekly.

That being said, staying up all night to study is one of the worst things students can do for their grades. In October of 2019, two MIT professors found a correlation between sleep and test scores : The less students slept during the semester, the worse their scores.

So, why is it that sleep is so important for test scores? While the answer seems simple, that students simply perform better when they’re not mentally or physically tired, the truth may be far more complicated and interesting.

In the last 20 years, scientists have found that sleep impacts more than just students’ ability to perform well; it improves their ability to learn, memorize, retain, recall, and use their new knowledge to solve problems creatively. All of which contribute to better test scores.

Let’s take a look at some of the most interesting research regarding the impact of sleep on learning and memory.

How does sleep improve the ability to learn?

When learning facts and information, most of what we learn is temporarily stored in a region of the brain called the hippocampus. Some scientists hypothesize that , like most storage centers, the hippocampus has limited storage capacity. This means, if the hippocampus is full, and we try to learn more information, we won’t be able to.

Fortunately, many scientists also hypothesize that sleep, particularly Stages 2 and 3 sleep, plays a role in replenishing our ability to learn. In one study, a group of 44 participants underwent two rigorous sessions of learning, once at noon and again at 6:00 PM. Half of the group was allowed to nap between sessions, while the other half took part in standard activities. The researchers found that the group that napped between learning sessions learned just as easily at 6:00 PM as they did at noon. The group that didn’t nap, however, experienced a significant decrease in learning ability [1].

How does sleep improve the ability to recall information?

Humans have known about the benefits of sleep for memory recall for thousands of years. In fact, the first record of this revelation is from the first century AD. Rhetorician Quintilian stated, “It is a curious fact, of which the reason is not obvious, that the interval of a single night will greatly increase the strength of the memory.”

In the last century, scientists have tested this theory many times, often finding that sleep improves memory retention and recall by between 20 and 40 percent. Recent research has led scientists to hypothesize that Stage 3 (deep non-Rapid Eye Movement sleep, or Slow Wave Sleep) may be especially important for the improvement of memory retention and recall [2].

How does sleep improve long-term memory?

Scientists hypothesize that sleep also plays a major role in forming long-term memories. According to Matthew Walker, professor of neuroscience and psychology at UC Berkeley, MRI scans indicate that the slow brain waves of stage 3 sleep (deep NREM sleep) “serve as a courier service,” transporting memories from the hippocampus to other more permanent storage sites [3].

How does sleep improve the ability to solve problems creatively?

Many tests are designed to assess critical thinking and creative problem-solving skills. Recent research has led scientists to hypothesize that sleep, particularly REM sleep, plays a role in strengthening these skills. In one study, scientists tested the effect of REM sleep on the ability to solve anagram puzzles (word scrambles like “EOUSM” for “MOUSE”), an ability that requires strong creative thinking and problem-solving skills.

In the study, participants solved a couple of anagram puzzles before going to sleep in a sleep laboratory with electrodes placed on their heads. The subjects were woken up four times during the night to solve anagram puzzles, twice during NREM sleep and twice during REM sleep.

The researchers found that when participants were woken up during REM sleep, they could solve 15 to 35 percent more puzzles than they could when woken up from NREM sleep. They also performed 15 to 35 percent better than they did in the middle of the day [4]. It seems that REM sleep may play a major role in improving the ability to solve complex problems.

So, what’s the point?

Sleep research from the last 20 years indicates that sleep does more than simply give students the energy they need to study and perform well on tests. Sleep actually helps students learn, memorize, retain, recall, and use their new knowledge to come up with creative and innovative solutions.

It’s no surprise that the MIT study previously mentioned revealed no improvement in scores for those who only prioritized their sleep the night before a big test. In fact, the MIT researchers concluded that if students want to see an improvement in their test scores, they have to prioritize their sleep during the entire learning process. Staying up late to study just doesn’t pay off.

Interested in learning more about the impact of sleep on learning and memory? Check out this Student Sleep Guide .

Author Biography

Kelly Cappello graduated from East Stroudsburg University of Pennsylvania with a B.A. in Interdisciplinary Studies in 2015. She is now a writer, specialized in researching complex topics and writing about them in simple English. She currently writes for Recharge.Energy , a company dedicated to helping the public improve their sleep and improve their lives.

- Mander, Bryce A., et al. “Wake Deterioration and Sleep Restoration of Human Learning.” Current Biology, vol. 21, no. 5, 2011, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.019.

- Walker M. P. (2009). The role of slow wave sleep in memory processing. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 5(2 Suppl), S20–S26.

- Walker, Matthew. Why We Sleep. Scribner, 2017.

- Walker, Matthew P, et al. “Cognitive Flexibility across the Sleep–Wake Cycle: REM-Sleep Enhancement of Anagram Problem Solving.” Cognitive Brain Research, vol. 14, no. 3, 2002, pp. 317–324., doi:10.1016/s0926-6410(02)00134-9.

Posted on Dec 21, 2020 | Tagged: learning and memory

© The Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania | Site best viewed in a supported browser . | Report Accessibility Issues and Get Help | Privacy Policy | Site Design: PMACS Web Team. | Sitemap

- See us on facebook

- See us on twitter

- See us on youtube

- See us on linkedin

- See us on instagram

Among teens, sleep deprivation an epidemic

Sleep deprivation increases the likelihood teens will suffer myriad negative consequences, including an inability to concentrate, poor grades, drowsy-driving incidents, anxiety, depression, thoughts of suicide and even suicide attempts.

October 8, 2015 - By Ruthann Richter

The most recent national poll shows that more than 87 percent of U.S. high school students get far less than the recommended eight to 10 hours of sleep each night. Christopher Silas Neal

Carolyn Walworth, 17, often reaches a breaking point around 11 p.m., when she collapses in tears. For 10 minutes or so, she just sits at her desk and cries, overwhelmed by unrelenting school demands. She is desperately tired and longs for sleep. But she knows she must move through it, because more assignments in physics, calculus or French await her. She finally crawls into bed around midnight or 12:30 a.m.

The next morning, she fights to stay awake in her first-period U.S. history class, which begins at 8:15. She is unable to focus on what’s being taught, and her mind drifts. “You feel tired and exhausted, but you think you just need to get through the day so you can go home and sleep,” said the Palo Alto, California, teen. But that night, she will have to try to catch up on what she missed in class. And the cycle begins again.

“It’s an insane system. … The whole essence of learning is lost,” she said.

Walworth is among a generation of teens growing up chronically sleep-deprived. According to a 2006 National Sleep Foundation poll, the organization’s most recent survey of teen sleep, more than 87 percent of high school students in the United States get far less than the recommended eight to 10 hours, and the amount of time they sleep is decreasing — a serious threat to their health, safety and academic success. Sleep deprivation increases the likelihood teens will suffer myriad negative consequences, including an inability to concentrate, poor grades, drowsy-driving incidents, anxiety, depression, thoughts of suicide and even suicide attempts. It’s a problem that knows no economic boundaries.

While studies show that both adults and teens in industrialized nations are becoming more sleep deprived, the problem is most acute among teens, said Nanci Yuan , MD, director of the Stanford Children’s Health Sleep Center . In a detailed 2014 report, the American Academy of Pediatrics called the problem of tired teens a public health epidemic.

“I think high school is the real danger spot in terms of sleep deprivation,” said William Dement , MD, PhD, founder of the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic , the first of its kind in the world. “It’s a huge problem. What it means is that nobody performs at the level they could perform,” whether it’s in school, on the roadways, on the sports field or in terms of physical and emotional health.

Social and cultural factors, as well as the advent of technology, all have collided with the biology of the adolescent to prevent teens from getting enough rest. Since the early 1990s, it’s been established that teens have a biologic tendency to go to sleep later — as much as two hours later — than their younger counterparts.

Yet when they enter their high school years, they find themselves at schools that typically start the day at a relatively early hour. So their time for sleep is compressed, and many are jolted out of bed before they are physically or mentally ready. In the process, they not only lose precious hours of rest, but their natural rhythm is disrupted, as they are being robbed of the dream-rich, rapid-eye-movement stage of sleep, some of the deepest, most productive sleep time, said pediatric sleep specialist Rafael Pelayo , MD, with the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic.

“When teens wake up earlier, it cuts off their dreams,” said Pelayo, a clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. “We’re not giving them a chance to dream.”

Teens have a biologic tendency to go to sleep later, yet many high schools start the day at a relatively early hour, disrupting their natural rhythym. Monkey Business/Fotolia

Understanding teen sleep

On a sunny June afternoon, Dement maneuvered his golf cart, nicknamed the Sleep and Dreams Shuttle, through the Stanford University campus to Jerry House, a sprawling, Mediterranean-style dormitory where he and his colleagues conducted some of the early, seminal work on sleep, including teen sleep.

Beginning in 1975, the researchers recruited a few dozen local youngsters between the ages of 10 and 12 who were willing to participate in a unique sleep camp. During the day, the young volunteers would play volleyball in the backyard, which faces a now-barren Lake Lagunita, all the while sporting a nest of electrodes on their heads.

At night, they dozed in a dorm while researchers in a nearby room monitored their brain waves on 6-foot electroencephalogram machines, old-fashioned polygraphs that spit out wave patterns of their sleep.

One of Dement’s colleagues at the time was Mary Carskadon, PhD, then a graduate student at Stanford. They studied the youngsters over the course of several summers, observing their sleep habits as they entered puberty and beyond.

Dement and Carskadon had expected to find that as the participants grew older, they would need less sleep. But to their surprise, their sleep needs remained the same — roughly nine hours a night — through their teen years. “We thought, ‘Oh, wow, this is interesting,’” said Carskadon, now a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University and a nationally recognized expert on teen sleep.

Moreover, the researchers made a number of other key observations that would plant the seed for what is now accepted dogma in the sleep field. For one, they noticed that when older adolescents were restricted to just five hours of sleep a night, they would become progressively sleepier during the course of the week. The loss was cumulative, accounting for what is now commonly known as sleep debt.

“The concept of sleep debt had yet to be developed,” said Dement, the Lowell W. and Josephine Q. Berry Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. It’s since become the basis for his ongoing campaign against drowsy driving among adults and teens. “That’s why you have these terrible accidents on the road,” he said. “People carry a large sleep debt, which they don’t understand and cannot evaluate.”

The researchers also noticed that as the kids got older, they were naturally inclined to go to bed later. By the early 1990s, Carskadon established what has become a widely recognized phenomenon — that teens experience a so-called sleep-phase delay. Their circadian rhythm — their internal biological clock — shifts to a later time, making it more difficult for them to fall asleep before 11 p.m.

Teens are also biologically disposed to a later sleep time because of a shift in the system that governs the natural sleep-wake cycle. Among older teens, the push to fall asleep builds more slowly during the day, signaling them to be more alert in the evening.

“It’s as if the brain is giving them permission, or making it easier, to stay awake longer,” Carskadon said. “So you add that to the phase delay, and it’s hard to fight against it.”

Pressures not to sleep

After an evening with four or five hours of homework, Walworth turns to her cellphone for relief. She texts or talks to friends and surfs the Web. “It’s nice to stay up and talk to your friends or watch a funny YouTube video,” she said. “There are plenty of online distractions.”

While teens are biologically programmed to stay up late, many social and cultural forces further limit their time for sleep. For one, the pressure on teens to succeed is intense, and they must compete with a growing number of peers for college slots that have largely remained constant. In high-achieving communities like Palo Alto, that translates into students who are overwhelmed by additional homework for Advanced Placement classes, outside activities such as sports or social service projects, and in some cases, part-time jobs, as well as peer, parental and community pressures to excel.

William Dement

At the same time, today’s teens are maturing in an era of ubiquitous electronic media, and they are fervent participants. Some 92 percent of U.S. teens have smartphones, and 24 percent report being online “constantly,” according to a 2015 report by the Pew Research Center. Teens have access to multiple electronic devices they use simultaneously, often at night. Some 72 percent bring cellphones into their bedrooms and use them when they are trying to go to sleep, and 28 percent leave their phones on while sleeping, only to be awakened at night by texts, calls or emails, according to a 2011 National Sleep Foundation poll on electronic use. In addition, some 64 percent use electronic music devices, 60 percent use laptops and 23 percent play video games in the hour before they went to sleep, the poll found. More than half reported texting in the hour before they went to sleep, and these media fans were less likely to report getting a good night’s sleep and feeling refreshed in the morning. They were also more likely to drive when drowsy, the poll found.

The problem of sleep-phase delay is exacerbated when teens are exposed late at night to lit screens, which send a message via the retina to the portion of the brain that controls the body’s circadian clock. The message: It’s not nighttime yet.

Yuan, a clinical associate professor of pediatrics, said she routinely sees young patients in her clinic who fall asleep at night with cellphones in hand.

“With academic demands and extracurricular activities, the kids are going nonstop until they fall asleep exhausted at night. There is not an emphasis on the importance of sleep, as there is with nutrition and exercise,” she said. “They say they are tired, but they don’t realize they are actually sleep-deprived. And if you ask kids to remove an activity, they would rather not. They would rather give up sleep than an activity.”

The role of parents

Adolescents are also entering a period in which they are striving for autonomy and want to make their own decisions, including when to go to sleep. But studies suggest adolescents do better in terms of mood and fatigue levels if parents set the bedtime — and choose a time that is realistic for the child’s needs. According to a 2010 study published in the journal Sleep , children are more likely to be depressed and to entertain thoughts of suicide if a parent sets a late bedtime of midnight or beyond.

In families where parents set the time for sleep, the teens’ happier, better-rested state “may be a sign of an organized family life, not simply a matter of bedtime,” Carskadon said. “On the other hand, the growing child and growing teens still benefit from someone who will help set the structure for their lives. And they aren’t good at making good decisions.”

They say they are tired, but they don’t realize they are actually sleep-deprived. And if you ask kids to remove an activity, they would rather not. They would rather give up sleep than an activity.

According to the 2011 sleep poll, by the time U.S. students reach their senior year in high school, they are sleeping an average of 6.9 hours a night, down from an average of 8.4 hours in the sixth grade. The poll included teens from across the country from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

American teens aren’t the worst off when it comes to sleep, however; South Korean adolescents have that distinction, sleeping on average 4.9 hours a night, according to a 2012 study in Sleep by South Korean researchers. These Asian teens routinely begin school between 7 and 8:30 a.m., and most sign up for additional evening classes that may keep them up as late as midnight. South Korean adolescents also have relatively high suicide rates (10.7 per 100,000 a year), and the researchers speculate that chronic sleep deprivation is a contributor to this disturbing phenomenon.

By contrast, Australian teens are among those who do particularly well when it comes to sleep time, averaging about nine hours a night, possibly because schools there usually start later.

Regardless of where they live, most teens follow a pattern of sleeping less during the week and sleeping in on the weekends to compensate. But many accumulate such a backlog of sleep debt that they don’t sufficiently recover on the weekend and still wake up fatigued when Monday comes around.

Moreover, the shifting sleep patterns on the weekend — late nights with friends, followed by late mornings in bed — are out of sync with their weekday rhythm. Carskadon refers to this as “social jet lag.”

“Every day we teach our internal circadian timing system what time it is — is it day or night? — and if that message is substantially different every day, then the clock isn’t able to set things appropriately in motion,” she said. “In the last few years, we have learned there is a master clock in the brain, but there are other clocks in other organs, like liver or kidneys or lungs, so the master clock is the coxswain, trying to get everybody to work together to improve efficiency and health. So if the coxswain is changing the pace, all the crew become disorganized and don’t function well.”

This disrupted rhythm, as well as the shortage of sleep, can have far-reaching effects on adolescent health and well-being, she said.

“It certainly plays into learning and memory. It plays into appetite and metabolism and weight gain. It plays into mood and emotion, which are already heightened at that age. It also plays into risk behaviors — taking risks while driving, taking risks with substances, taking risks maybe with sexual activity. So the more we look outside, the more we’re learning about the core role that sleep plays,” Carskadon said.

Many studies show students who sleep less suffer academically, as chronic sleep loss impairs the ability to remember, concentrate, think abstractly and solve problems. In one of many studies on sleep and academic performance, Carskadon and her colleagues surveyed 3,000 high school students and found that those with higher grades reported sleeping more, going to bed earlier on school nights and sleeping in less on weekends than students who had lower grades.

Sleep is believed to reinforce learning and memory, with studies showing that people perform better on mental tasks when they are well-rested. “We hypothesize that when teens sleep, the brain is going through processes of consolidation — learning of experiences or making memories,” Yuan said. “It’s like your brain is filtering itself — consolidating the important things and filtering out those unimportant things.” When the brain is deprived of that opportunity, cognitive function suffers, along with the capacity to learn.

“It impacts academic performance. It’s harder to take tests and answer questions if you are sleep-deprived,” she said.

That’s why cramming, at the expense of sleep, is counterproductive, said Pelayo, who advises students: Don’t lose sleep to study, or you’ll lose out in the end.

The panic attack

Chloe Mauvais, 16, hit her breaking point at the end of a very challenging sophomore year when she reached “the depths of frustration and anxiety.” After months of late nights spent studying to keep up with academic demands, she suffered a panic attack one evening at home.

“I sat in the living room in our house on the ground, crying and having horrible breathing problems,” said the senior at Menlo-Atherton High School. “It was so scary. I think it was from the accumulated stress, the fear over my grades, the lack of sleep and the crushing sense of responsibility. High school is a very hard place to be.”

We hypothesize that when teens sleep, the brain is going through processes of consolidation — learning of experiences or making memories. It’s like your brain is filtering itself.

Where she once had good sleep habits, she had drifted into an unhealthy pattern of staying up late, sometimes until 3 a.m., researching and writing papers for her AP European history class and prepping for tests.

“I have difficulty remembering events of that year, and I think it’s because I didn’t get enough sleep,” she said. “The lack of sleep rendered me emotionally useless. I couldn’t address the stress because I had no coherent thoughts. I couldn’t step back and have perspective. … You could probably talk to any teen and find they reach their breaking point. You’ve pushed yourself so much and not slept enough and you just lose it.”

The experience was a kind of wake-up call, as she recognized the need to return to a more balanced life and a better sleep pattern, she said. But for some teens, this toxic mix of sleep deprivation, stress and anxiety, together with other external pressures, can tip their thinking toward dire solutions.

Research has shown that sleep problems among adolescents are a major risk factor for suicidal thoughts and death by suicide, which ranks as the third-leading cause of fatalities among 15- to 24-year-olds. And this link between sleep and suicidal thoughts remains strong, independent of whether the teen is depressed or has drug and alcohol issues, according to some studies.

“Sleep, especially deep sleep, is like a balm for the brain,” said Shashank Joshi, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford. “The better your sleep, the more clearly you can think while awake, and it may enable you to seek help when a problem arises. You have your faculties with you. You may think, ‘I have 16 things to do, but I know where to start.’ Sleep deprivation can make it hard to remember what you need to do for your busy teen life. It takes away the support, the infrastructure.”

Sleep is believed to help regulate emotions, and its deprivation is an underlying component of many mood disorders, such as anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder. For students who are prone to these disorders, better sleep can help serve as a buffer and help prevent a downhill slide, Joshi said.

Rebecca Bernert, PhD, who directs the Suicide Prevention Research Lab at Stanford, said sleep may affect the way in which teens process emotions. Her work with civilians and military veterans indicates that lack of sleep can make people more receptive to negative emotional information, which they might shrug off if they were fully rested, she said.

“Based on prior research, we have theorized that sleep disturbances may result in difficulty regulating emotional information, and this may lower the threshold for suicidal behaviors among at-risk individuals,” said Bernert, an instructor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. Now she’s studying whether a brief nondrug treatment for insomnia reduces depression and risk for suicide.

Sleep deprivation also has been shown to lower inhibitions among both adults and teens. In the teen brain, the frontal lobe, which helps restrain impulsivity, isn’t fully developed, so teens are naturally prone to impulsive behavior. “When you throw into the mix sleep deprivation, which can also be disinhibiting, mood problems and the normal impulsivity of adolescence, then you have a potentially dangerous situation,” Joshi said.

Some schools shift

Given the health risks associated with sleep problems, school districts around the country have been looking at one issue over which they have some control: when school starts in the morning. The trend was set by the town of Edina, Minnesota, a well-to-do suburb of Minneapolis, which conducted a landmark experiment in student sleep in the late 1990s. It shifted the high school’s start time from 7:20 a.m. to 8:30 a.m. and then asked University of Minnesota researchers to look at the impact of the change. The researchers found some surprising results: Students reported feeling less depressed and less sleepy during the day and more empowered to succeed. There was no comparable improvement in student well-being in surrounding school districts where start times remained the same.

With these findings in hand, the entire Minneapolis Public School District shifted start times for 57,000 students at all of its schools in 1997 and found similarly positive results. Attendance rates rose, and students reported getting an hour’s more sleep each school night — or a total of five more hours of sleep a week — countering skeptics who argued that the students would respond by just going to bed later.

For the health and well-being of the nation, we should all be taking better care of our sleep, and we certainly should be taking better care of the sleep of our youth.

Other studies have reinforced the link between later start times and positive health benefits. One 2010 study at an independent high school in Rhode Island found that after delaying the start time by just 30 minutes, students slept more and showed significant improvements in alertness and mood. And a 2014 study in two counties in Virginia found that teens were much less likely to be involved in car crashes in a county where start times were later, compared with a county with an earlier start time.

Bolstered by the evidence, the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2014 issued a strong policy statement encouraging middle and high school districts across the country to start school no earlier than 8:30 a.m. to help preserve the health of the nation’s youth. Some districts have heeded the call, though the decisions have been hugely contentious, as many consider school schedules sacrosanct and cite practical issues, such as bus schedules, as obstacles.

In Fairfax County, Virginia, it took a decade of debate before the school board voted in 2014 to push back the opening school bell for its 57,000 students. And in Palo Alto, where a recent cluster of suicides has caused much communitywide soul-searching, the district superintendent issued a decision in the spring, over the strenuous objections of some teachers, students and administrators, to eliminate “zero period” for academic classes — an optional period that begins at 7:20 a.m. and is generally offered for advanced studies.

Certainly, changing school start times is only part of the solution, experts say. More widespread education about sleep and more resources for students are needed. Parents and teachers need to trim back their expectations and minimize pressures that interfere with teen sleep. And there needs to be a cultural shift, including a move to discourage late-night use of electronic devices, to help youngsters gain much-needed rest.

“At some point, we are going to have to confront this as a society,” Carskadon said. “For the health and well-being of the nation, we should all be taking better care of our sleep, and we certainly should be taking better care of the sleep of our youth.”

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu .

Hope amid crisis

Psychiatry’s new frontiers

- Close Menu Search

- Recommend a Story

The Lion's Roar

May 24 Party Like It’s 1989: Lions Capture the 2024 Diamond Classic

May 24 Why Does the Early 20th Century Tend to Spark Nostalgia?

May 24 O.J Simpson Dead at 76: Football Star Turned Murderer

May 24 NAIA Bans Transgender Women From Women’s Sports

May 24 From Papyrus to Ashes: The Story of the Great Library of Alexandria

The Effects Homework Can Have On Teens’ Sleeping Habits

Jess Amabile '24 and February 25, 2021

Ever wonder why you feel like you never get enough sleep? Here’s a pretty good reason: large amounts of homework can be detrimental to a teen’s sleeping habits, even more so with high schoolers.

There have been many studies recently about the damage homework has to students’ health, mainly concerning lack of sleep in teenagers. According to an article published by US News called “The Importance of Sleep for Teen Mental Health” , it states that “ surveys show that less than 9 percent of teens get enough sleep”. This fact is devastating, especially considering the fact that teenagers take up about thirteen percent of the country’s population.

Also mentioned in “The Importance of Sleep for Teen Mental Health” , “ about forty-one million Americans get six or fewer hours of sleep per night”. If teenagers see their parents not getting enough sleep, it can convince them that there are things more important than sleep, such as something almost every teenager in America has to deal with–homework.

Homework is pretty stressful for teens, especially if they have other things to do. Many teens have long hours at school, which limits the time for them to do their insane amount of homework, attend extra-curricular activities, eat, do whatever they need to around the house, and sleep. And usually, sleeping is the last thing on the list of things to do before school the next day. Another article, “What’s preventing adequate teen sleep” , states that, “Homework is possibly the biggest factor that keeps teens from getting enough sleep…The sheer quantity of homework absorbs hours that should be dedicated to sleep”. Students generally have so much homework that they don’t have enough time to do everything else they need to do that day. So, sleeping is often the first thing teens eliminate from their schedule.

According to Oxford Learning , homework can have other negative effects on students. In their article, Oxford Learning remarks, “56 percent of students considered homework a primary source of stress. Too much homework can result in lack of sleep, headaches, exhaustion, and weight loss”.

Similarly, Stanford Medicine News Center reports that the founder of the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic stated, “‘I think high school is the real danger spot in terms of sleep deprivation,’ said William Dement, MD, Ph.D.”. Sleep deprivation is a real problem for high school students, and Stanford Medicine News Center continues on this topic by commenting, “Sleep deprivation increases the likelihood teens will suffer myriad negative consequences, including an inability to concentrate, poor grades, drowsy-driving incidents, anxiety, depression, thoughts of suicide and even suicide attempts. It’s a problem that knows no economic boundaries”. If students are constantly battling sleep deprivation, how can they concentrate on schoolwork, or even be able to perform everyday tasks? This shows that homework greatly affects students in both mental and physical ways. If something is supposed to continue a lesson that was learned in school, why is it negatively affecting students’ lives?

Ask yourself: is homework really worth the extremely negative effects?

“What’s preventing adequate teen sleep”

http://sleepeducation.org/news/2017/07/26/what-is-preventing-adequate-teen-sleep

“The Importance of Sleep for Teen Mental Health”

https://health.usnews.com/health-care/for-better/articles/2018-07-02/the-importance-of-sleep-for-teen-mental-health

Oxford Learning

https://www.oxfordlearning.com/how-does-homework-affect-students/#:~:text=How%20Does%20Homework%20Affect%20Students,headaches%2C%20exhaustion%20and%20weight%20loss.

Stanford Medicine News Center

https://med.stanford.edu/news.html

What time should high school should start?

- 7:00 AM or earlier

- 7:30 AM (Current Start Time)

- After 9:00 AM

View Results

- Polls Archive

The Rebellion Against Instagram’s Unrealistic Body Expectations

News Consumption On Social Media

The Sound of Music

3 Underrated Old Hollywood Actresses That Everyone Should Know

The Timeline of Shirley Chisholm

6 Influential Black Americans That Schools Failed to Teach You About

West Lions Save Lives: SGO’s 2024 Blood Drive

TIMELINE: The College Application Process

Santa Claus: Has He Become a Fraud and Only a Model for Greed to Children?

George Santos Expelled From House of Representatives

Comments (0)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Login to your account

If you don't remember your password, you can reset it by entering your email address and clicking the Reset Password button. You will then receive an email that contains a secure link for resetting your password

If the address matches a valid account an email will be sent to __email__ with instructions for resetting your password

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Status | |

| Version | |

| Ad File | |

| Disable Ads Flag | |

| Environment | |

| Moat Init | |

| Moat Ready | |

| Contextual Ready | |

| Contextual URL | |

| Contextual Initial Segments | |

| Contextual Used Segments | |

| AdUnit | |

| SubAdUnit | |

| Custom Targeting | |

| Ad Events | |

| Invalid Ad Sizes |

Access provided by

Download started.

- Academic & Personal: 24 hour online access

- Corporate R&D Professionals: 24 hour online access

- Add To Online Library Powered By Mendeley

- Add To My Reading List

- Export Citation

- Create Citation Alert

Self-report surveys of student sleep and well-being: a review of use in the context of school start times

- Terra D. Ziporyn, PhD Terra D. Ziporyn Correspondence Corresponding author. Contact Affiliations Start School Later, Inc, PO Box 6105, Annapolis, MD 21146 Search for articles by this author

- Beth A. Malow, MD, MS Beth A. Malow Affiliations Sleep Disorders Division, Department of Neurology, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, 1161 21st Ave South, Room A-0116 MCN,Nashville, TN 37232-2551 Search for articles by this author

- Kari Oakes, PA Kari Oakes Affiliations Start School Later, Inc, PO Box 6105, Annapolis, MD 21146 Search for articles by this author

- Kyla L. Wahlstrom, PhD Kyla L. Wahlstrom Affiliations Department of Organizational Leadership, Policy and Development, College of Education and Human Development, University of Minnesota, 210C Burton Hall, Minneapolis, MN 55455 Search for articles by this author

- School start times

- Adolescents

- High school

- United States

- School districts

- Sleep duration

- Teen sleep surveys

- Self-reports

Purchase one-time access:

- For academic or personal research use, select 'Academic and Personal'

- For corporate R&D use, select 'Corporate R&D Professionals'

- Drobnich D.

- Scopus (52)

- Google Scholar

- Minnesota Sleep Society

- Wolfson A.R.

- Carskadon M.A.

- Scopus (1330)

- Wahlstrom K.

- Peterson K.

- Wahlstrom K.L.

- Berger A.T.

- Scopus (44)

- Full Text PDF

- Scopus (26)

- Boergers J.

- Scopus (159)

- Scopus (333)

- Phillips B.

- Scopus (184)

- McKeever P.M.

- Scopus (28)

- Thacher P.V.

- Onyper S.V.

- Scopus (65)

- Perez-Lloret S.

- Videla A.J.

- Richaudeau A.

- Scopus (69)

- Tzischinsky O.

- Scopus (108)

- Urrila A.S.

- Massicotte J.

- Scopus (76)

- Groeger J.A.

- Adolescent Sleep Working Group Committee on Adolescence

- Scopus (934)

- Vorona R.D.

- Szklo-Coxe M.

- Lamichhane R.

- McNallen A.

- Leszczyszyn D.

- Wheaton A.G.

- Miller G.F.

- Scopus (101)

- Meininger J.C.

- Gallagher M.R.

- Nguyen T.Q.

- Scopus (29)

- Chaput J.P.

- Scopus (151)

- Shomaker L.B.

- Scopus (24)

- Krueger P.M.

- Reither E.N.

- Peppard P.E.

- Burger A.E.

- Scopus (116)

- McKnight-Eily L.R.

- Presley-Cantrell L.

- Scopus (280)

- Cohen-Zion M.

- Scopus (561)

- Dearth-Wesley T.

- Whitaker R.C.

- Iglowstein I.

- Molinari L.

- Scopus (1028)

- Scopus (603)

- Fredriksen K.

- Scopus (369)

- Thorleifsdottir B.

- Bjornsson J.K.

- Benediktsdottir B.

- Gislason T.

- Kristbjarnarson H.

- Scopus (259)

- Scopus (242)

- Achermann P.

- Scopus (354)

- Scopus (162)

- American Medical Association

- Adolescent Sleep Working Group Committee on Adolescence and Council on School Health

- Scopus (310)

- Watson N.F.

- Martin J.L.

- Scopus (84)

- Liverpool Central School District

- Cherry Creek School District

- Defranco T.

- Barnett D.E.

- Dunietz G.L.

- Matos-Moreno A.

- Singer D.C.

- O'Brien L.M.

- Chervin R.D.

- Scopus (10)

- Morgenthaler T.I.

- Mullington J.

- Scopus (31)

- Tanner-Smith E.E.

- Davison C.M.

- Chapman D.P.

- Scopus (205)

- Merikangas K.

- Avenevoli S.

- Costello J.

- Kessler R.C.

- Scopus (255)

- Stanford Graduate School of Education

- Kandel D.B.

- Scopus (797)

- Scopus (868)

- School Sleep Habits Survey

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Brener N.D.

- Scopus (74)

- Fairfax County VA

- Thellman K.E.

- Dmitrieva J.

- LeBourgeois M.K.

- Scopus (88)

- Scopus (63)

- Faris M.A.E.

- Al-Hilali M.M.

- Scopus (33)

- Rothrock N.

- Scopus (2220)

- Meltzer L.J.

- Reynolds A.C.

- Crabtree V.M.

- Bevans K.B.

- Scopus (94)

- Forrest C.B.

- Scopus (35)

- Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS)

- Spilsbury J.C.

- Scopus (126)

- Burduvali E.

- Jefferson C.

- Giannotti F.

- Scopus (327)

- Morgenthaler T.

- Friedman L.

- Scopus (911)

- Scopus (565)

- Scopus (186)

Article info

Publication history, identification.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2017.09.002

ScienceDirect

Related articles.

- Download Hi-res image

- Download .PPT

- Access for Developing Countries

- Articles & Issues

- Articles In Press

- Current Issue

- List of Issues

- Special Issues

- Supplements

- For Authors

- Author Information

- Download Conflict of Interest Form

- Researcher Academy

- Submit a Manuscript

- Style Guidelines for In Memoriam

- Download Online Journal CME Program Application

- NSF CME Mission Statement

- Professional Practice Gaps in Sleep Health

- Journal Info

- About the Journal

- Activate Online Access

- Information for Advertisers

- Career Opportunities

- Editorial Board

- New Content Alerts

- Press Releases

- More Periodicals

- Find a Periodical

- Go to Product Catalog

The content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Accessibility

- Help & Contact

Session Timeout (2:00)

Your session will expire shortly. If you are still working, click the ‘Keep Me Logged In’ button below. If you do not respond within the next minute, you will be automatically logged out.

Homework could have an impact on kids’ health. Should schools ban it?

Professor of Education, Penn State

Disclosure statement

Gerald K. LeTendre has received funding from the National Science Foundation and the Spencer Foundation.

Penn State provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Reformers in the Progressive Era (from the 1890s to 1920s) depicted homework as a “sin” that deprived children of their playtime . Many critics voice similar concerns today.

Yet there are many parents who feel that from early on, children need to do homework if they are to succeed in an increasingly competitive academic culture. School administrators and policy makers have also weighed in, proposing various policies on homework .

So, does homework help or hinder kids?

For the last 10 years, my colleagues and I have been investigating international patterns in homework using databases like the Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) . If we step back from the heated debates about homework and look at how homework is used around the world, we find the highest homework loads are associated with countries that have lower incomes and higher social inequality.

Does homework result in academic success?

Let’s first look at the global trends on homework.

Undoubtedly, homework is a global phenomenon ; students from all 59 countries that participated in the 2007 Trends in Math and Science Study (TIMSS) reported getting homework. Worldwide, only less than 7% of fourth graders said they did no homework.

TIMSS is one of the few data sets that allow us to compare many nations on how much homework is given (and done). And the data show extreme variation.

For example, in some nations, like Algeria, Kuwait and Morocco, more than one in five fourth graders reported high levels of homework. In Japan, less than 3% of students indicated they did more than four hours of homework on a normal school night.

TIMSS data can also help to dispel some common stereotypes. For instance, in East Asia, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan – countries that had the top rankings on TIMSS average math achievement – reported rates of heavy homework that were below the international mean.

In the Netherlands, nearly one out of five fourth graders reported doing no homework on an average school night, even though Dutch fourth graders put their country in the top 10 in terms of average math scores in 2007.

Going by TIMSS data, the US is neither “ A Nation at Rest” as some have claimed, nor a nation straining under excessive homework load . Fourth and eighth grade US students fall in the middle of the 59 countries in the TIMSS data set, although only 12% of US fourth graders reported high math homework loads compared to an international average of 21%.

So, is homework related to high academic success?

At a national level, the answer is clearly no. Worldwide, homework is not associated with high national levels of academic achievement .

But, the TIMSS can’t be used to determine if homework is actually helping or hurting academic performance overall , it can help us see how much homework students are doing, and what conditions are associated with higher national levels of homework.

We have typically found that the highest homework loads are associated with countries that have lower incomes and higher levels of social inequality – not hallmarks that most countries would want to emulate.

Impact of homework on kids

TIMSS data also show us how even elementary school kids are being burdened with large amounts of homework.

Almost 10% of fourth graders worldwide (one in 10 children) reported spending multiple hours on homework each night. Globally, one in five fourth graders report 30 minutes or more of homework in math three to four times a week.

These reports of large homework loads should worry parents, teachers and policymakers alike.

Empirical studies have linked excessive homework to sleep disruption , indicating a negative relationship between the amount of homework, perceived stress and physical health.

What constitutes excessive amounts of homework varies by age, and may also be affected by cultural or family expectations. Young adolescents in middle school, or teenagers in high school, can study for longer duration than elementary school children.

But for elementary school students, even 30 minutes of homework a night, if combined with other sources of academic stress, can have a negative impact . Researchers in China have linked homework of two or more hours per night with sleep disruption .

Even though some cultures may normalize long periods of studying for elementary age children, there is no evidence to support that this level of homework has clear academic benefits . Also, when parents and children conflict over homework, and strong negative emotions are created, homework can actually have a negative association with academic achievement.

Should there be “no homework” policies?

Administrators and policymakers have not been reluctant to wade into the debates on homework and to formulate policies . France’s president, Francois Hollande, even proposed that homework be banned because it may have inegaliatarian effects.

However, “zero-tolerance” homework policies for schools, or nations, are likely to create as many problems as they solve because of the wide variation of homework effects. Contrary to what Hollande said, research suggests that homework is not a likely source of social class differences in academic achievement .

Homework, in fact, is an important component of education for students in the middle and upper grades of schooling.

Policymakers and researchers should look more closely at the connection between poverty, inequality and higher levels of homework. Rather than seeing homework as a “solution,” policymakers should question what facets of their educational system might impel students, teachers and parents to increase homework loads.

At the classroom level, in setting homework, teachers need to communicate with their peers and with parents to assure that the homework assigned overall for a grade is not burdensome, and that it is indeed having a positive effect.

Perhaps, teachers can opt for a more individualized approach to homework. If teachers are careful in selecting their assignments – weighing the student’s age, family situation and need for skill development – then homework can be tailored in ways that improve the chance of maximum positive impact for any given student.

I strongly suspect that when teachers face conditions such as pressure to meet arbitrary achievement goals, lack of planning time or little autonomy over curriculum, homework becomes an easy option to make up what could not be covered in class.

Whatever the reason, the fact is a significant percentage of elementary school children around the world are struggling with large homework loads. That alone could have long-term negative consequences for their academic success.

- Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS)

- Elementary school

- Academic success

Lecturer in Indigenous Health (Identified)

Lecturer in Visual Art

PhD Scholarship

Senior Lecturer, HRM or People Analytics

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

We don't ship to your address!

- Choose your country

- Czech Republic

- Liechtenstein

- The Netherlands

- The United Kingdom

- kr. DANSK KRONE

- € EURO

- Ft MAGYAR FORINT

- £ POUND

- kr SVENSK KRONA

- zł ZłOTY

We're here to help

- Customer service

- Business-to-Business

- Shipping information

- Frequently asked questions

- Terms and Conditions

No products

You have to add to cart at least 0 bottles or any program to make checkout.

We are here to help you

How Does Homework Affect Students Sleep?

Published: June 21st, 2023

Exploring how homework affects students' sleep is an essential part of understanding the overall health and academic performance of our youth. The correlation between heavy workload from assignments and sleep deprivation has been a subject of multiple studies, with compelling findings.

Understanding the correlation between homework and teenage stress

Exploring the impact on quality sleep due to excessive homework, how late-night study impacts the circadian rhythm, the link between disturbed sleep patterns and academic performance, unpacking research findings linking heavy homework load with mental health issues, implications for future educational policies regarding home-based tasks, evaluating pros & cons related to assigning extensive workloads at elementary levels, suggesting alternatives for effective learning without compromising children's wellbeing, alfie kohn's perspective on education system practices, proposing changes toward balanced school schedules, assessing potential benefits shifting school start times based upon nsf recommendations, effective time management strategies, the impact of sleep deprivation on students, does homework affect sleep schedules, what percentage of students lose sleep due to homework, why does school cause sleep deprivation, why is sleep more important than homework.

This blog post delves into the impact that excessive homework can have on high school students' quality sleep, and how it might disrupt their natural circadian rhythm or sleep cycle. We will also explore its implications on mental health issues among younger kids who are often encouraged to go to bed earlier but struggle due to late-night study sessions.

The role of American education system practices in contributing to student's lack of adequate rest will be examined along with Alfie Kohn’s perspective about current education policies. Additionally, we'll discuss early school start times as another potential burden leading towards disturbed sleeping patterns.

Finally, we aim at proposing some changes for more balanced school schedules and providing tips for effectively managing time amidst academic responsibilities and extracurricular activities without being sleep deprived.

The Impact of Homework on Teenage Stress and Sleep

Homework is a major source of stress for teenagers, affecting their sleep patterns. According to studies, about 75% of high school students report grades and homework as significant stressors. This anxiety can lead to sleep deprivation, with over 50% of students reporting insufficient rest.

A heavy workload not only affects academic performance but also disrupts the normal sleep cycle. The pressure to excel academically leads many students into a vicious cycle where they stay up late completing tasks, wake up early for school, and end up being sleep deprived.

This lack of rest impairs cognitive functions like memory retention and problem-solving skills - both crucial for academic success. Furthermore, inadequate sleep may lead to ailments such as reduced immunity or persistent tiredness.

Sleep experts recommend that younger kids should go to bed earlier than teens because their biological clock naturally prompts them to feel sleepy around 8-9 PM. However, this becomes challenging when burdened with loads of assignments which extend their screen time significantly beyond recommended limits.

The blue light emitted by electronic devices used for studying suppresses melatonin production - a hormone that regulates our body's internal clock determining when we feel sleepy or awake (National Sleep Foundation). Consequently, these factors combined make falling asleep more difficult leading towards disrupted sleeping patterns ultimately affecting overall well-being including mental health status alongside academic performance negatively.

In conclusion, there needs to be an urgent reevaluation of how much work is assigned outside class hours considering potential adverse effects upon student's health, especially concerning adequate rest necessary for optimal functioning throughout day-to-day activities, whether within academia or other extracurricular responsibilities undertaken during leisure periods post-school schedules.

Analyzing Sleep Patterns Among Stressed Students

High schoolers are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of sleep deprivation due to the demands of juggling academics and extracurriculars. The pressure of balancing academics with extracurricular activities can lead to late nights and early mornings, leaving them feeling perpetually tired and impacting their academic performance.

The human body operates on a 24-hour internal clock known as the circadian rhythm. This biological process regulates our sleep-wake cycle, among other things. When students stay up late studying or completing homework, they disrupt this natural rhythm which can result in a range of health issues including chronic fatigue and weakened immunity.

Screen time is another factor that exacerbates this issue. Many students use electronic devices for research or writing assignments before bed, exposing themselves to blue light which further interferes with their circadian rhythms.

Regular slumber is a must for cognitive functions, such as memory consolidation and problem-solving aptitude - fundamental aspects of learning. Multiple studies have shown that when these patterns are disturbed due to excessive homework or late-night study sessions, it can negatively affect academic performance.

- Poor Concentration: Lack of adequate rest makes focusing on tasks more difficult, leading to decreased productivity during study hours.

- Inability To Retain Information: During deep stages of sleep, information from short-term memory gets transferred into long-term storage enabling better recall later; deprived individuals miss out on this critical process.

- Deteriorating Mental Health: Chronic lack of rest has been linked with increased levels of anxiety and depression amongst teenagers, impacting overall wellbeing and indirectly affecting grades too.

A report by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) suggests there's an urgent need for schools to address these concerns seriously, considering the potential repercussions over students' physical and mental health alongside scholastic achievements. Making sure they get enough quality rest each night is essential for optimal functioning throughout the day, both inside and outside the classroom environments.

Investigating Time Spent on Homework and Its Effects on Mental Health

The amount of time spent on homework and studying significantly affects students' mental health. Multiple studies have shown that an excessive workload can lead to depression, stress, and sleep deprivation .

A comprehensive study involving 2386 adolescents assessed various aspects, including self-rated health, overweight status, and depression symptoms, alongside time spent on homework/studying. The researchers used ten different multiple linear regression models to test the association with the global Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale score. This approach allowed them to analyze how each aspect correlates with the others.

The results were revealing: there was a clear correlation between increased hours dedicated to home-based tasks and higher levels of depressive tendencies among high school students . These effects weren't limited only to academic performance but extended into their personal lives as well, affecting relationships, participation rates in extracurricular activities , and more.

This data suggests that we need a more balanced approach when it comes to assigning workloads at schools. Instead of piling up assignments indiscriminately, educators should aim for an optimal balance where learning is enhanced rather than hindered by excessive amounts of homework.

In light of this information, some countries are already taking steps towards reducing screen time requirements, especially during after-school hours. This allows younger kids to go to bed earlier, improving their sleep cycle quality significantly, which ultimately leads to better cognitive functioning the next day at school or other engagements they might have outside the academic context, like part-time jobs or family duties.

To sum up, a healthy balance between academic and other life obligations is essential to avoid potential repercussions in all aspects of a student's life. Neglecting to strike a balance between academic and other responsibilities can have severe repercussions, not only in terms of grades but also emotionally, socially, and mentally. Therefore, it is imperative to address this issue promptly and effectively with all stakeholders involved in the education sector worldwide today, tomorrow, and onwards too.

Excessive Workload Strain from Assignments in Younger Kids

The ongoing discussion about the implications of homework for younger students has drawn attention from educators, parents, and researchers. While assignments can reinforce what students learn during school hours, evidence supporting benefits from home-based tasks remains scarce before high-school levels. This is concerning considering the potential adverse effects an excessive workload can have on young minds.

On one hand, homework can instill discipline and help develop good study habits. On the other hand, too much of it could lead to sleep deprivation among younger kids who should ideally be going to bed earlier. The AAP suggests that 6-12 year olds should have 9-12 hours of rest, however this can be hard to attain when they are inundated with assignments.

Besides affecting their sleep cycle, overburdening them with academic responsibilities also leaves little room for extracurricular activities which play a crucial role in their overall development. It may even result in screen time replacing physical activity as children turn towards digital platforms to complete their assignments.

Rather than piling up work indiscriminately, schools could consider adopting strategies aimed at enhancing learning while ensuring the well-being of students. For instance, project-based learning could be an effective alternative where students actively explore real-world problems and challenges, thereby gaining deeper knowledge.

In addition to this approach would be limiting daily homework duration per grade level or introducing "homework-free" days during weekends or holidays providing ample rest periods essential for growth development amongst younger kids.

This shift not only ensures that our future generations aren't sleep deprived due to unnecessary academic pressure but also fosters a love for lifelong learning - something far more valuable than mere grades obtained through rote memorization.

American Education's Role In Student Sleep Deprivation

It's common for students in the US to be sleep deprived , not just because of academic pressures but also due to extracurricular activities . Late nights and early mornings disrupt a healthy sleep cycle , affecting student wellbeing.

Educational critic Alfie Kohn argues that the American education system emphasizes homework without considering its impact on student wellbeing. Many tasks assigned do not enhance learning but rather contribute towards stress and sleep deprivation among students. You can read more about his thoughts in his article titled " The Truth About Homework: Needless Assignments Persist Because of Widespread Misconceptions About Learning. "

Kohn suggests a shift towards assigning work aimed at enhancing learning rather than piling it up indiscriminately. Schools should recognize the importance of adequate rest for optimal functioning.

- Reduce homework loads: Lightening the load could help alleviate some of the pressure students feel, allowing them time to relax and get enough sleep each night.