Cost Allocation – Meaning, Importance, Process and More

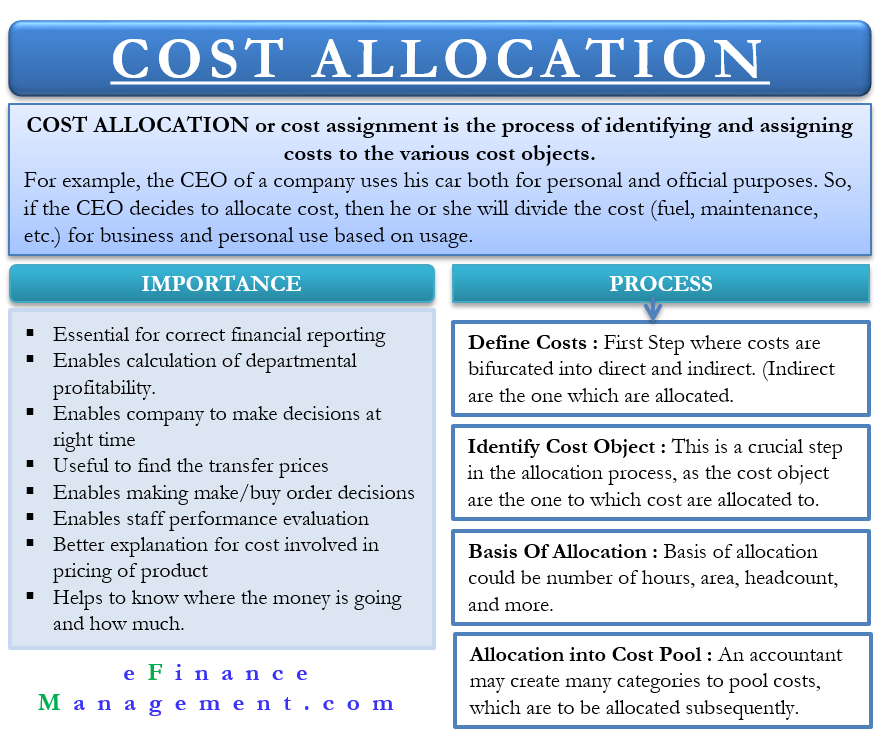

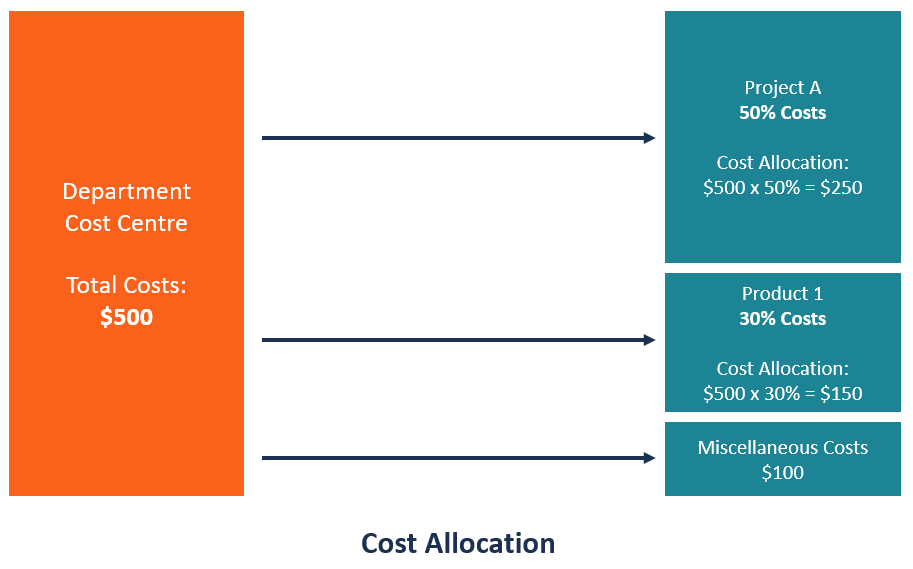

Cost Allocation or cost assignment is the process of identifying and assigning costs to the various cost objects. These cost objects could be those for which the company needs to find out the cost separately. A few examples of cost objects can be a product, customer, project, department, and so on.

The need for cost allocation arises because some costs are not directly attributable to the particular cost object. In other words, these costs are incurred for various objects, and then the sum is split and allocated to multiple cost objects. These costs are generally indirect. Since these costs are not directly traceable, an accountant uses their due diligence to allocate these costs in the best possible way. It results in an allocation that could be partially arbitrary, and thus, many refer cost allocation exercise as the spreading of a cost.

Examples of Cost Allocation

- Cost Allocation – Importance

Cost Allocation Method

Define costs, identify cost objects, basis of allocation, accumulate costs into cost pool.

For example, a company’s CEO uses his car for personal and official purposes. So, if the CEO decides to allocate costs, then they will divide the cost (fuel, maintenance, etc.) for business and personal use based on usage.

The following examples will help us understand the cost allocation concept better:

- A company has a building in which there are various departments. One can allocate depreciation costs to the department on the basis square ft area of each department. This cost will then be further assigned to the products on which the department works.

- An accountant can attribute electricity that a production facility consumes to different departments. Then the accountant can assign the department’s electricity cost to the products that the department works on.

- An employee works on three products for a month. To attribute their salary to three products, an accountant can use the number of hours the employee gave to each product.

Cost Allocation – Importance

The following points reflect the importance of allocating costs:

- Allocating cost is essential for financial reporting, i.e., to correctly assign the cost among the cost objects.

- It allows the company to calculate the true profitability of the department or function. This profitability could serve as the basis for making further decisions for that department or service.

- If cost allocation is correct, it allows the business to identify and understand the costs at each stage and their impact on the profit or loss. On the other hand, if the allocation is incorrect, the company may end up making wrong or inconsistent decisions concerning the distribution of resources amongst various cost objects.

- The concept is also useful for finding the transfer prices when there is a transaction between subsidiaries.

- It helps a company make better economic decisions, such as whether or not to accept a new order.

- One can also use the concept to evaluate the performance of the staff.

- It helps in better explaining to the customers the costs that went into the pricing of a product or service.

- Allocation cost helps a company know where the money is going and how much. It will assist the company in using the resources effectively. Pool costs, if not allocated, may give an unbalanced view of the cost of various objects.

As such, there is no specific method to allocate costs. So, an accountant needs to use his or her due diligence to assign a cost to the cost object. Of course, they are considering the practice adopted in a similar industry. For instance, the accountant may decide to allocate expenses based on headcount, area, weightage, and so on.

Also Read: Cost Object – Meaning, Advantages, Types and More

Irrespective of the method an accountant uses, their objective should be to allocate the cost as fairly as possible. Or to allocate cost in a way that is in line with the nature of the cost object. Or to lower the arbitrariness in awarding costs.

Several efforts are underway to better cost allocation techniques. For instance, the overhead allocation for manufacturers, which was on plant-wide rates, is now based on departmental standards. Also, accountants use machine hours instead of direct labor hours for allocation.

Moreover, some accountants are also implementing activity-based costing to better the allocation. So, there can be several ways to allocate costs. But, whatever form the company selects, it is essential to document the reasons backing that method, and that need to be followed consistently for several periods.

A company can ensure documentation by developing allocation formulas or tables. Moreover, if a company wants, it can also pass supporting journal entries to transfer costs to the cost objects or do it via the chargeback module in the ERP system.

Also Read: Cost Hierarchy – Meaning, Levels and Example

Nowadays, cost allocation systems are available to assist in cost allocation. Such systems track the entity that produces the goods or services and the body that consumes those goods or services. The system also identifies the basis to distribute the cost.

The process to Allocate cost

As said above, there are no specific methods for allocating costs. Similarly, there is no particular process for it, as well. However, the process we are detailing is one of the most popular, and many companies use it for allocating costs. Following is the process:

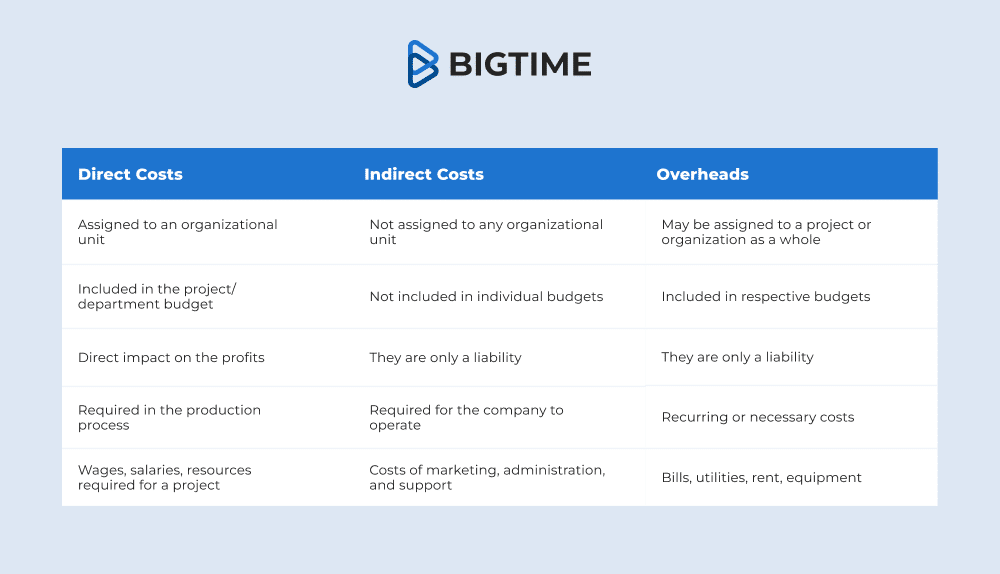

Before allocating the cost, a company must define the various types of costs. Generally, there are three types of costs – direct, indirect, and overhead. Direct costs are those that one can easily attribute to a product or service, such as wages to factory workers or raw material for the specific product.

Indirect costs are ones that a company needs to incur for its operations, such as administration costs. Primarily, these are the costs that a company needs to allocate as it is difficult to attribute them directly to a product or service or any other cost object.

Another type of cost is an overhead cost , which is also an indirect cost. These costs are incurred for the production and selling of goods or services. Such costs do not vary based on production or sales. A company needs to pay them even if it is not producing or selling anything. Research and development costs, rent, etc., are good examples of such a cost.

The company or the accountant must know the cost objects for which they need to allocate the cost. It is crucial as we can’t assign costs to something on which we have no information. A cost object could be the product, customer, region, department, etc.

Along with the cost object , the company must also determine the basis on which it would allocate the cost. This basis could be the number of hours, area, headcount, and more. For example, if headcount is the basis of allocation for insurance costs and a company has 500 employees, then the department with 100 employees will account for 20% of the insurance cost. Experts recommend choosing a cost allocation base that is a crucial cost driver as well.

A cost driver is a variable whose increase or decrease leads to an increase or decrease in the cost as well. For instance, the number of purchase orders could be a cost driver for the cost of the purchasing department.

An accountant may create many categories to pool costs, which are to be allocated subsequently. It is the account head where the costs should be accumulated before assigning them to the cost objects. Cost pools can be insurance, fuel consumption, electricity, rent, depreciation, etc. The selection of the cost pool primarily depends on the use of the cost allocation base.

Continue reading – Costing Terms .

RELATED POSTS

- Cost Structure

- Types of Costs and their Classification

- Cost Accounting and Management Accounting

- Types of Cost Accounting

- Cost Accumulation: Meaning, Types, and More

- Types of Costing

Sanjay Bulaki Borad

MBA-Finance, CMA, CS, Insolvency Professional, B'Com

Sanjay Borad, Founder of eFinanceManagement, is a Management Consultant with 7 years of MNC experience and 11 years in Consultancy. He caters to clients with turnovers from 200 Million to 12,000 Million, including listed entities, and has vast industry experience in over 20 sectors. Additionally, he serves as a visiting faculty for Finance and Costing in MBA Colleges and CA, CMA Coaching Classes.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Sign me up for the newsletter!

Our Recommendations

- Best Small Business Loans for 2024

- Businessloans.com Review

- Biz2Credit Review

- SBG Funding Review

- Rapid Finance Review

- 26 Great Business Ideas for Entrepreneurs

- Startup Costs: How Much Cash Will You Need?

- How to Get a Bank Loan for Your Small Business

- Articles of Incorporation: What New Business Owners Should Know

- How to Choose the Best Legal Structure for Your Business

Small Business Resources

- Business Ideas

- Business Plans

- Startup Basics

- Startup Funding

- Franchising

- Success Stories

- Entrepreneurs

- The Best Credit Card Processors of 2024

- Clover Credit Card Processing Review

- Merchant One Review

- Stax Review

- How to Conduct a Market Analysis for Your Business

- Local Marketing Strategies for Success

- Tips for Hiring a Marketing Company

- Benefits of CRM Systems

- 10 Employee Recruitment Strategies for Success

- Sales & Marketing

- Social Media

- Best Business Phone Systems of 2024

- The Best PEOs of 2024

- RingCentral Review

- Nextiva Review

- Ooma Review

- Guide to Developing a Training Program for New Employees

- How Does 401(k) Matching Work for Employers?

- Why You Need to Create a Fantastic Workplace Culture

- 16 Cool Job Perks That Keep Employees Happy

- 7 Project Management Styles

- Women in Business

- Personal Growth

- Best Accounting Software and Invoice Generators of 2024

- Best Payroll Services for 2024

- Best POS Systems for 2024

- Best CRM Software of 2024

- Best Call Centers and Answering Services for Busineses for 2024

- Salesforce vs. HubSpot: Which CRM Is Right for Your Business?

- Rippling vs Gusto: An In-Depth Comparison

- RingCentral vs. Ooma Comparison

- Choosing a Business Phone System: A Buyer’s Guide

- Equipment Leasing: A Guide for Business Owners

- HR Solutions

- Financial Solutions

- Marketing Solutions

- Security Solutions

- Retail Solutions

- SMB Solutions

Business News Daily provides resources, advice and product reviews to drive business growth. Our mission is to equip business owners with the knowledge and confidence to make informed decisions. As part of that, we recommend products and services for their success.

We collaborate with business-to-business vendors, connecting them with potential buyers. In some cases, we earn commissions when sales are made through our referrals. These financial relationships support our content but do not dictate our recommendations. Our editorial team independently evaluates products based on thousands of hours of research. We are committed to providing trustworthy advice for businesses. Learn more about our full process and see who our partners are here .

What Is Cost Allocation?

Cost allocation is a process businesses use to identify costs. Here's everything you need to know.

Table of Contents

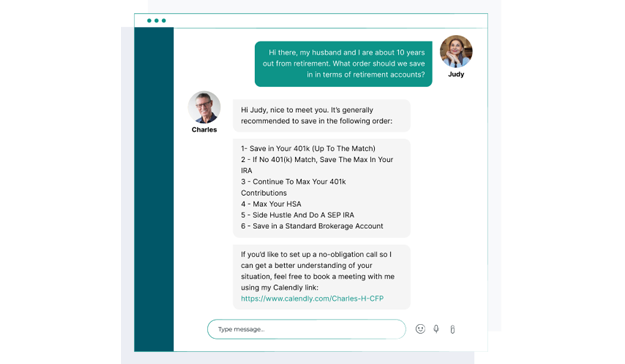

Entrepreneurs, small business owners and managers need accurate, timely financial data to run their operations. Specifically, understanding and connecting costs to items or departments helps them create budgets, develop strategies and make the best business decisions for their organizations. This is where cost allocation comes in. Detailed cost allocation reports help businesses ensure they’re charging enough to cover expenses and make a profit.

While a detailed cost allocation report may not be vital for extremely small businesses, more complex businesses require cost allocation to optimize profitability and productivity.

What is cost allocation?

Cost allocation is the process of identifying and assigning costs to business objects, such as products, projects, departments or individual company branches. Business owners use cost allocation to calculate profitability. Costs are separated or allocated, into different categories based on the business area they impact. These amounts are then used in accounting reports .

For example, say you’re a small clothing manufacturer. Your product line’s cost allocation would include materials, shipping and labor costs. It would also include a portion of the operation’s overhead costs. Calculating these costs consistently helps business leaders determine if profits from sales are higher than the costs of producing the product line. If not, it can help the owner pinpoint where to raise prices or cut expenses .

For a larger company, cost allocation is applied to each department or business location . Many companies also use cost allocation to determine annual bonuses for each area.

Types of costs

If you’re starting a business , the cost allocation process is relatively straightforward. However, larger businesses have many more costs that can be divided into two primary categories: direct and indirect costs:

- Purchased inventory

- Materials used to make inventory

- Direct labor costs for employees who make inventory

- Payroll for those who work in operations

- Manufacturing overhead, including rent, insurance and utilities costs

- Other overhead costs, including expenses that support the company but aren’t directly related to production, such as marketing and human resources

What is a cost driver?

A cost driver is a variable that affects business costs, such as the number of invoices issued, employee hours worked or units of electricity used. Unlike cost objects, such as units produced or departments, a cost driver reflects the reason for the incurred cost amounts.

How to allocate costs

While cost objects vary by business type, the cost allocation process is the same regardless of what your company produces. Here are the steps involved.

1. Identify your business’s cost objects.

Determine the cost objects to which you want to allocate costs, such as units of production, number of employees or departments. Remember that anything within your business that generates an expense is a cost object. Review each product line, project and department to ensure you’ve gathered all cost objects for which you must allocate costs.

2. Create a cost pool.

Next, create a detailed list of all business costs. Categories should cover utilities, business insurance policies, rent and any other expenses your business incurs.

3. Choose the best cost allocation method for your needs.

After identifying your business’s cost objects and creating a cost pool, you must choose a cost allocation method. Several methods exist, including the following standard ones:

- Direct materials cost method: This cost allocation method assumes all products have the same allocation base and variable rate.

- Direct labor cost method: This cost allocation method is most helpful if labor costs can be allocated to one product or if expenses vary directly with labor costs.

- High/low method. This cost allocation method is best if you have more than one cost driver and each driver has different fixed or variable rates.

- Step-up or step-down method: With this cost allocation method, departments are first ranked and then the cost of services is allocated from one service department to another in a series of steps.

- Full absorption costing (FAC): This cost allocation method combines direct material and direct labor costs with a predetermined FAC rate based on company historical data or industry standards.

- Variable costing: Consider this cost allocation method if your business has many variable cost allocations (costs that vary by quantity) and uses significant direct labor.

4. Allocate costs.

Now that you’ve listed cost objects, created a cost pool and chosen a cost allocation method, you’re ready to allocate costs.

Here’s a cost allocation example to help you visualize the process:

Dave owns a business that manufactures eyeglasses. In January, Dave’s overhead costs totaled $5,000. In the same month, he produced 3,000 eyeglasses with $2 in direct labor per product. Direct materials for each pair of eyeglasses totaled $5. Here’s what cost allocation would look like for Dave: Direct costs: $5 direct materials + $2 direct labor = $7 direct costs per pair Indirect costs: Overhead allocation: $5,000 ÷ 3,000 pairs = $1.66 overhead costs per pair Direct costs: $7 per pair + Indirect costs: $1.66 per pair Total cost: $8.66 per pair

As you can see, cost allocation helps Dave determine how much he must charge wholesale for each pair of eyeglasses to make a profit. Larger companies would apply this same process to each department and product to ensure sufficient sales goals.

5. Review and adjust cost allocations.

Cost allocations are never static. To be meaningful, they must be monitored and adjusted constantly as circumstances change.

What are the benefits of cost allocation?

Accurate, regular cost allocation can bring your business the following benefits:

- Helps you run your business: The information you glean from cost allocation reports helps you perform vital functions like preparing income tax returns and creating financial reports for investors, creditors and regulators.

- Informs business decisions: Cost allocation is an excellent business decision tool that can help you monitor productivity and justify expenses. Cost allocation gives a detailed overview of how your business expenses are used. From this perspective, you can determine which products and services are profitable and which departments are most productive.

- Helps produce accurate business reports: Tax accounting, financial accounting and management accounting all require some kind of cost allocation. This information is the foundation of accurate business reports.

- Can reveal accurate production costs: Knowing what it costs to create a product, including all expenses allocated to it, is essential to making good pricing decisions and allocating resources efficiently.

- Helps you evaluate staff: Cost allocation can help you assess the performance of different departments and staff members. If a department is not profitable, staff productivity may need improvement.

Common cost allocation mistakes

To get the most from cost allocation, avoid these common mistakes:

- Equal or inflexible allocation : Cost allocation is not as simple as allocating any given cost over different product lines or departments. Some cost objects require more time, expense or labor than others, for example.

- Missing costs: Costing is meaningless if it doesn’t include all expenses. Don’t forget costs, such as overhead, time spent and intangible expenses.

- Failing to adjust as needed: Costs and priorities in business are changing constantly. Be sure your cost allocations are monitored and adjusted to meet your information needs.

- Not considering fluctuating revenue with indirect costs: If your business is seasonal or fluctuates over time, it’s important to account for that when allocating costs.

Cost allocation and your business

Even if you operate a very small business, it’s essential to properly allocate your expenses. Otherwise, you could make all-too-common mistakes, such as charging too little for your product or spending too much on overhead. Whether you choose to start allocating costs on your own with software or with the help of a professional small business accountant , cost allocation is a process no business owner can afford to overlook.

Dachondra Cason contributed to this article.

Building Better Businesses

Insights on business strategy and culture, right to your inbox. Part of the business.com network.

Cost Allocation: Methods & Calculations for Improved Profitability

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

What was that invoice for and where did that other bill come from?

Unfortunately, for numerous professional services companies, these questions are asked way too often. Fortunately, there is one way to prevent this situation from happening — it’s called cost allocation .

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Define cost allocation and the factors that affect it.

- Identify the cost objects that need to be taken into account in the process.

- Use the cost allocation formula and cost allocation method to assign expenditures to departments and projects with accuracy.

Cost Allocation Definition

Cost allocation is the process of matching the cost objects with the departments or operations that generate them. It is mostly used for calculating the financial performance of a company or its parts, such as teams or projects, and determining where given cost objects came from.

For example, in a typical services company, costs can be allocated to non-production departments (i.e. marketing, sales, administration), as well as projects and teams.

What is cost allocation used for?

What’s the point of calculating all of these things?

While cost allocation is very helpful when it’s time to sum up employee performance, results of particular project managers, or finances that may interest stakeholders, there are other perks.

On a daily basis, cost allocation can also help you:

- Ensure budgets are on track — both the budget of the entire company, as well as the finances of particular departments or projects.

- Identify the aspects of operations that generate excessive costs and act on that information.

- Check whether the company is spending money on the right endeavors.

In other words, cost allocation is the process of identifying the sources of the company’s costs and evaluating their importance.

Types of Costs in Cost Allocation

Cost allocation involves all the people and assets in the organization. Therefore, it includes dozens of different types of costs that project managers and executives need to take into consideration while managing project budgets and other finances.

Let’s take a look at the types of costs in cost allocation.

Basic Costs in Cost Allocation

In the simplest classification system possible, costs in a cost allocation are divided into 3 categories:

Direct Costs

Direct costs in cost allocation are spendings that have already been attributed to certain departments, projects, or teams, and there are no doubts as to their origin. These costs contribute to the profit billable operations are supposed to generate as they are required in the production processes.

For example, in a service company, direct costs are usually included in the project budget, or even a project timeline in general. They usually refer to wages and salaries, but they may also include other resources required for the project. Therefore, allocating this type of cost is a piece of cake, as they are generated directly by the department, services, or other cost objects they are related to.

Indirect Costs

The definition of indirect costs in cost allocation is a bit more complicated, especially for endeavors closely related to professional services. These costs are not associated with any organizational unit in particular; they are simply needed to keep the company running and growing.

Indirect costs usually include support staff wages and spendings made by the support staff that help the production department do its job. These include cost objects such as marketing and sales specialists, administrative employees, and any other support departments. Indirect costs also often include internal projects.

However, there is one more type of indirect cost in cost allocation that we need to consider — the overhead costs.

Overhead Costs

Overhead costs cover all the costs that need to be continually paid regardless of the company’s business performance.

Project Overheads vs Organizational Overheads

Overhead costs are usually divided into 2 categories:

- Project overheads, for example, equipment, subscriptions, and programs.

- Organizational overheads, such as utilities, bills, rent, etc.

- Cost of services needed to keep the company running, e.g. security expenses and business management.

Cost Allocation Method

At this point, you may ask yourself, “how can I allocate costs on my own?” Fortunately, the answer to this question is not as complicated as it may seem — here’s a cost allocation method that can help you.

Cost Allocation Method Example

Some organizations, particularly services companies, profit only from their projects, and they don’t need to allocate the costs for the entire business — they just need to share the costs between the profitable operations and departments, as well as other cost objects. Here’s what the process of identifying them looks like.

1. Define Which Costs You Want to Allocate

Begin by calculating the costs you want to allocate in the first place. For example, if you want to allocate the cost of utilities in your office, add them up to get a bigger picture.

For the sake of this cost allocation example, let’s assume that The Best Company is focused on allocating the costs of its support departments to the project for the month (also known as business overhead). The costs include:

- The costs of the marketing department: $40,000

- The costs of administration: $15,000

- The costs of the sales department: $45,000

Together, all these departments account for $100,000 of additional overhead expenses that need to be allocated.

2. Determine the Base for Sharing the Costs

Depending on the type of business, you can divide the costs based on different factors. The most popular ones include:

- Billable hours tracked in the services

- Generated income

- Generated profit

For this example, we’ll use the first of these indicators — billable hours. This method is considered the simplest way of allocating costs proportionally.

The Best Company has 2 projects — Project A and Project B.

To complete all the activities planned in Project A for the month, the project managers and their team members will need 1,800 hours. For Project B, the number of hours needed is 1,200. Both projects combined require 3,000 hours to complete. Therefore, Project A accounts for 60% of all billable hours in the company, while Project B includes 40% of them. These are the proportions we’re going to use in this cost allocation method.

3. Allocate the Costs Proportionally

If Project A includes 60% of all billable hours while Project B accounts for 40% of them, we can now use the numbers to determine the distribution of costs between them. Let’s focus on identifying how they should each contribute to costs.

According to the examples above, the total amount of costs to be shared among billable operations is $100,000. Project B requires more hours, therefore it should account for a larger chunk of the costs — exactly 60% of them. As a result, $60,000 of the costs are allocated to the project.

Project B, meanwhile, requires 40% of all the billable hours. Therefore, it should pay 40% of the costs — $40,000.

Benefits of Cost Allocation

While cost allocation is a burden, it’s also a huge business advantage.

With cost allocation, you can:

- Determine whether your projects are profitable.

- Learn what part each project plays in covering the organizational costs.

- Check whether the company’s rates are high enough to cover all the costs and generate profits.

- Determine whether indirect costs are eating up the majority of the company’s profits.

- Identify the actual cost of services you provide to your customers.

- Find out which departments are spending more or less money, and what they use it for.

- Assign any lost spending to the people, teams, or departments responsible for them.

- Calculate the real profitability of your business as a whole.

Ready to get started?

Recommended for you

Hindsight is 2020: Lessons learned and predictions for the PS industry

3 tips for more effective time tracking for consultants.

16 Years Later: Engineering Firm Founder Shares His 3 Secrets to Success

- Author: Erik Hooijer

- Date: 02-10-2023

The Art of Cost Allocation: Strategies for Effective Resource Distribution

Cost allocation is a crucial pillar of financial management. It governs how organizations assign costs to various departments, projects, or products to ensure transparency and accountability. Mastering the art of cost allocation can pave the way for better financial decision-making, resource distribution, and overall operational efficiency. This comprehensive guide will explore strategies to perfect this art, ensuring that your organization benefits from optimized resource distribution.

Understanding Cost Allocation

Before diving into the strategies, it’s imperative to grasp the concept of cost allocation. The term Cost Allocation is often used interchangeably with Activity Based Costing (ABC) is the process of distributing costs across multiple sectors or products within an organization. Cost allocation not only aids in understanding the true cost of a product or service, but also helps in pricing, budgeting, and overall financial management.

There are four different strategies to master the cost allocation process. We will explain them below.

- Direct Allocation : This is the most straightforward method of cost allocation which directly traces costs to specific departments or products. This method is most effective when the cost incurrence is clear-cut and directly linked to a particular segment.

- Step-down Allocation : Service departments allocate costs to operating departments in this method. Once a service department has allocated its costs, it no longer receives subsequent allocations. This method is sequential and follows a specific order.

- Reciprocal Allocation : This is for scenarios where inter-departmental services exist. Each department allocates costs to other departments and receives costs in return, making it the most comprehensive method.

- Activity-Based Costing (ABC): This modern approach allocates costs based on activities that consume resources. Identifying cost drivers (activities causing costs) provides a more accurate picture of cost allocation.

Factors to Consider in Cost Allocation

Causality in cost allocation is a fundamental factor that underscores the importance of assigning costs directly to their clear cause-and-effect relationship. This principle is critical for achieving fairness and accuracy in cost allocation processes.

Another factor is consistency. Consistency is pivotal in cost allocation, emphasizing stability and uniformity in the methods employed for assigning costs over time. Maintaining consistency in cost allocation practices is essential for preserving the comparability of financial data across different periods.

Traceability is a critical principle within cost management, emphasizing the necessity of being able to track costs back to their origin. This is essential for enhancing accountability and transparency within an organization’s financial operations. By ensuring you can trace back every cost to its source, organizations establish a transparent and auditable trail that promotes accountability among individuals and departments responsible for incurring costs.

Simplicity is another crucial consideration in cost allocation. While accuracy is undoubtedly important, it’s essential to strike a balance and avoid overly complex allocation methods that can become counterproductive. Aiming for simplicity in cost allocation processes makes them more manageable and understandable and ensures that the effort put into allocation doesn’t outweigh the benefits. Striving for this balance helps organizations streamline their financial operations while still achieving the necessary level of accuracy in cost assignment.

Benefits of Effective Cost Allocation

When used appropriately, cost allocation can sculpt an organization’s robust financial landscape. Some of the proven benefits are:

- Informed Decision-making: With a clear understanding of costs, management can make more informed operational and strategic decisions.

- Enhanced Accountability: Departments or projects bearing costs are more likely to use resources efficiently.`

- Accurate Pricing: Products or services can be priced more accurately when their true costs are understood.

- Improved Budgeting: Budgets can be set more realistically and effectively when costs are allocated correctly.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls

Missteps in cost allocation can distort financial insights significantly, and it’s crucial to avoid certain pitfalls. Over-generalization, where costs are allocated too broadly, can obscure the expenses associated with specific departments or products, leading to inaccurate assessments. Additionally, it’s essential not to disregard intangible costs, such as brand reputation, even though they are harder to quantify. These should still be incorporated into the allocation process for a more comprehensive view. Lastly, employing static approaches can be detrimental as the business environment evolves; it’s essential to regularly review and update cost allocation methods to ensure they remain relevant and reflective of current circumstances and needs.

Cost allocation is not merely a financial exercise; it’s an art. The strategies we’ve explored are tools that, when used appropriately, can sculpt a robust financial landscape for an organization. The art of cost allocation is all about ensuring that every dollar spent is accounted for, every resource is utilized optimally, and every financial decision is made with a crystal-clear understanding of its implications. By mastering these strategies and being aware of potential pitfalls, organizations can set a foundation for sustainable growth, profitability, and long-term success.

Note Terms like Cost Allocation can be often interchangeably with others. If you hear someone using a term like Cost Modeling, Cost Management, A ctivity Based Costing (ABC), don’t sweat the difference. People and companies will have their own preferred term, but here at CostPerform, we often used Cost Allocation.

Are you ready for a 1 to 2-day reduction on your monthly book close process?

Download our white paper on corporate allocations, developed in collaboration with maryville consulting group..

+1 410 385 5325 [email protected]

CostPerform The Netherlands

+31 (0) 85 023 2114 [email protected] ACADEMY SUPPORT

- Time-driven Activity-Based Costing

- Capacity Management

- Multi-dimensional costing

- Technology Business Management

- Regulatory reporting

- Customer profitability

- Financial Institution

- IT services

- Manufacturing and Logistics

- Download brochure

- Online demo

- Download price list

- Become a partner

- Support Center

- Subscribe to our newsletter

ISO 27001 certified

© costperform 2024 | privacy policy | cookie statement | cookie preferences | terms of use.

Exercise Set B

LO 10.1 Calculate the goods available for sale for Soros Company, in units and in $ (dollar amounts), given the following facts about their inventory for the period.

LO 10.1 X Company accepts goods on consignment from C Company, and also purchases goods from P Company during the current month. X Company plans to sell the merchandise to customers during the following month. In each of these independent situations, who owns the merchandise at the end of the current month, and should therefore include it in their company’s ending inventory? Choose X, C, or P.

- Goods ordered from P, in transit, with shipping terms FOB destination.

- Goods ordered from P, in transit, with shipping terms FOB shipping point.

- Goods ordered from P, inventory in stock, held in storage until floor space is available.

- Goods ordered from C, inventory in stock, set aside for customer pickup and payments to finalize sale.

LO 10.1 Considering the following information, and applying the lower-of-cost-or-market approach, what is the correct value that should be reported on the balance sheet for the inventory?

LO 10.2 Complete the missing piece of information involving the changes in inventory, and their relationship to goods available for sale, for the two years shown.

LO 10.2 Bleistine Company had the following transactions for the month.

Calculate the ending inventory dollar value for each of the following cost allocation methods, using periodic inventory updating. Provide your calculations.

- first-in, first-out (FIFO)

- last-in, first-out (LIFO)

- weighted average (AVG)

Calculate the gross margin for the period for each of the following cost allocation methods, using periodic inventory updating. Assume that all units were sold for $50 each. Provide your calculations.

LO 10.2 Prepare journal entries to record the following transactions, assuming periodic inventory updating and first-in, first-out (FIFO) cost allocation.

LO 10.3 Calculate the cost of goods sold dollar value for B65 Company for the month, considering the following transactions under three different cost allocation methods and using perpetual inventory updating. Provide calculations for first-in, first-out (FIFO).

LO 10.3 Calculate the cost of goods sold dollar value for B66 Company for the month, considering the following transactions under three different cost allocation methods and using perpetual inventory updating. Provide calculations for last-in, first-out (LIFO).

LO 10.3 Calculate the cost of goods sold dollar value for B67 Company for the month, considering the following transactions under three different cost allocation methods and using perpetual inventory updating. Provide calculations for weighted average (AVG).

LO 10.3 Prepare journal entries to record the following transactions, assuming perpetual inventory updating and first-in, first-out (FIFO) cost allocation. Assume no beginning inventory.

LO 10.3 Prepare journal entries to record the following transactions, assuming perpetual inventory updating and last-in, first-out (LIFO) cost allocation. Assume no beginning inventory.

LO 10.4 If a group of inventory items costing $3,200 had been double counted during the year-end inventory count, what impact would the error have on the following inventory calculations? Indicate the effect (and amount) as either (a) none, (b) understated $______, or (c) overstated $______.

| Inventory Item | None or amount? | Understated or overstated? |

|---|---|---|

| Beginning Inventory | ||

| Purchases | ||

| Goods Available for Sale | ||

| Ending Inventory | ||

| Cost of Goods Sold |

LO 10.4 If Barcelona Company’s ending inventory was actually $122,000, but the cost of consigned goods, with a cost value of $20,000 were accidentally included with the company assets, when making the year-end inventory adjustment, what would be the impact on the presentation of the balance sheet and income statement for the year that the error occurred, if any?

LO 10.4 Tanke Company reported net income on the year-end financial statements of $850,200. However, errors in inventory were discovered after the reports were issued. If inventory was overstated by $21,000, how much net income did the company actually earn?

LO 10.5 Compute Westtown Company’s (A) inventory turnover ratio and (B) number of days’ sales in inventory ratio, using the following information.

LO 10.5 Complete the missing pieces of Delgado Company’s inventory calculations and ratios.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-financial-accounting/pages/1-why-it-matters

- Authors: Mitchell Franklin, Patty Graybeal, Dixon Cooper

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Accounting, Volume 1: Financial Accounting

- Publication date: Apr 11, 2019

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-financial-accounting/pages/1-why-it-matters

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-financial-accounting/pages/10-exercise-set-b

© Dec 13, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Cost Allocation

The process of identifying, accumulating, and assigning costs to costs objects

What is Cost Allocation?

Cost allocation is the process of identifying, accumulating, and assigning costs to costs objects such as departments, products, programs, or a branch of a company. It involves identifying the cost objects in a company, identifying the costs incurred by the cost objects, and then assigning the costs to the cost objects based on specific criteria.

When costs are allocated in the right way, the business is able to trace the specific cost objects that are making profits or losses for the company. If costs are allocated to the wrong cost objects, the company may be assigning resources to cost objects that do not yield as much profits as expected.

Types of Costs

There are several types of costs that an organization must define before allocating costs to their specific cost objects. These costs include:

1. Direct costs

Direct costs are costs that can be attributed to a specific product or service, and they do not need to be allocated to the specific cost object. It is because the organization knows what expenses go to the specific departments that generate profits and the costs incurred in producing specific products or services . For example, the salaries paid to factory workers assigned to a specific division is known and does not need to be allocated again to that division.

2. Indirect costs

Indirect costs are costs that are not directly related to a specific cost object like a function, product, or department. They are costs that are needed for the sake of the company’s operations and health. Some common examples of indirect costs include security costs, administration costs, etc. The costs are first identified, pooled, and then allocated to specific cost objects within the organization.

Indirect costs can be divided into fixed and variable costs. Fixed costs are costs that are fixed for a specific product or department. An example of a fixed cost is the remuneration of a project supervisor assigned to a specific division. The other category of indirect cost is variable costs, which vary with the level of output. Indirect costs increase or decrease with changes in the level of output.

3. Overhead costs

Overhead costs are indirect costs that are not part of manufacturing costs. They are not related to the labor or material costs that are incurred in the production of goods or services. They support the production or selling processes of the goods or services. Overhead costs are charged to the expense account, and they must be continually paid regardless of whether the company is selling goods or not.

Some common examples of overhead costs are rental expenses, utilities, insurance, postage and printing, administrative and legal expenses , and research and development costs.

Cost Allocation Mechanism

The following are the main steps involved when allocating costs to cost objects:

1. Identify cost objects

The first step when allocating costs is to identify the cost objects for which the organization needs to separately estimate the associated cost. Identifying specific cost objects is important because they are the drivers of the business, and decisions are made with them in mind.

The cost object can be a brand , project, product line, division/department, or a branch of the company. The company should also determine the cost allocation base, which is the basis that it uses to allocate the costs to cost objects.

2. Accumulate costs into a cost pool

After identifying the cost objects, the next step is to accumulate the costs into a cost pool, pending allocation to the cost objects. When accumulating costs, you can create several categories where the costs will be pooled based on the cost allocation base used. Some examples of cost pools include electricity usage, water usage, square footage, insurance, rent expenses , fuel consumption, and motor vehicle maintenance.

What is a Cost Driver?

A cost driver causes a change in the cost associated with an activity. Some examples of cost drivers include the number of machine-hours, the number of direct labor hours worked, the number of payments processed, the number of purchase orders, and the number of invoices sent to customers.

Benefits of Cost Allocation

The following are some of the reasons why cost allocation is important to an organization:

1. Assists in the decision-making process

Cost allocation provides the management with important data about cost utilization that they can use in making decisions. It shows the cost objects that take up most of the costs and helps determine if the departments or products are profitable enough to justify the costs allocated. For unprofitable cost objects, the company’s management can cut the costs allocated and divert the money to other more profitable cost objects.

2. Helps evaluate and motivate staff

Cost allocation helps determine if specific departments are profitable or not. If the cost object is not profitable, the company can evaluate the performance of the staff members to determine if a decline in productivity is the cause of the non-profitability of the cost objects.

On the other hand, if the company recognizes and rewards a specific department for achieving the highest profitability in the company, the employees assigned to that department will be motivated to work hard and continue with their good performance.

Additional Resources

Thank you for reading CFI’s guide to Cost Allocation. In order to help you become a world-class financial analyst and advance your career to your fullest potential, these additional resources will be very helpful:

- Break-Even Analysis

- Cost of Production

- Fixed and Variable Costs

- Projecting Income Statement Line Items

- See all accounting resources

- Share this article

Create a free account to unlock this Template

Access and download collection of free Templates to help power your productivity and performance.

Already have an account? Log in

Supercharge your skills with Premium Templates

Take your learning and productivity to the next level with our Premium Templates.

Upgrading to a paid membership gives you access to our extensive collection of plug-and-play Templates designed to power your performance—as well as CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs.

Already have a Self-Study or Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Access Exclusive Templates

Gain unlimited access to more than 250 productivity Templates, CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs, hundreds of resources, expert reviews and support, the chance to work with real-world finance and research tools, and more.

Already have a Full-Immersion membership? Log in

What is the Cost Allocation? (Definition, Example, and How the Cost Allocation Works)

Cost allocation, direct cost allocation, indirect cost, steps of cost allocation, 1- cost identification, 2- identify the basis of allocation, 3- cost allocation, examples of cost allocation, 1- transparency, 2- decision making, 3- waste reduction, 4- enhanced reporting, limitations, process complications, traditional vs. abc system of cost allocation, related posts, 4 best account payable books of all time – recommended, what are the purposes of budgeting, just-in-time: history, objective, productions, and purchasing, absorption costing: definition, formula, calculation, and example.

Cost Allocation

Written by True Tamplin, BSc, CEPF®

Reviewed by subject matter experts.

Updated on June 08, 2023

Get Any Financial Question Answered

Table of contents.

Cost allocation is a process in which businesses and individuals identify the costs incurred by activity and distribute them to appropriate accounts .

This allows for better decision-making when determining how much should be spent on different business areas.

Types of Costs

There are types of costs to consider during the process of cost allocation. They include:

- Fixed costs . These are expenses that remain the same no matter how many units of production have been made or sold. For example, a business spends $100,000 on rent every month. Even if the company can only produce and sell 50 units of a product in one month (when they normally make and sell 100), this cost remains at $100,000 for that given time period.

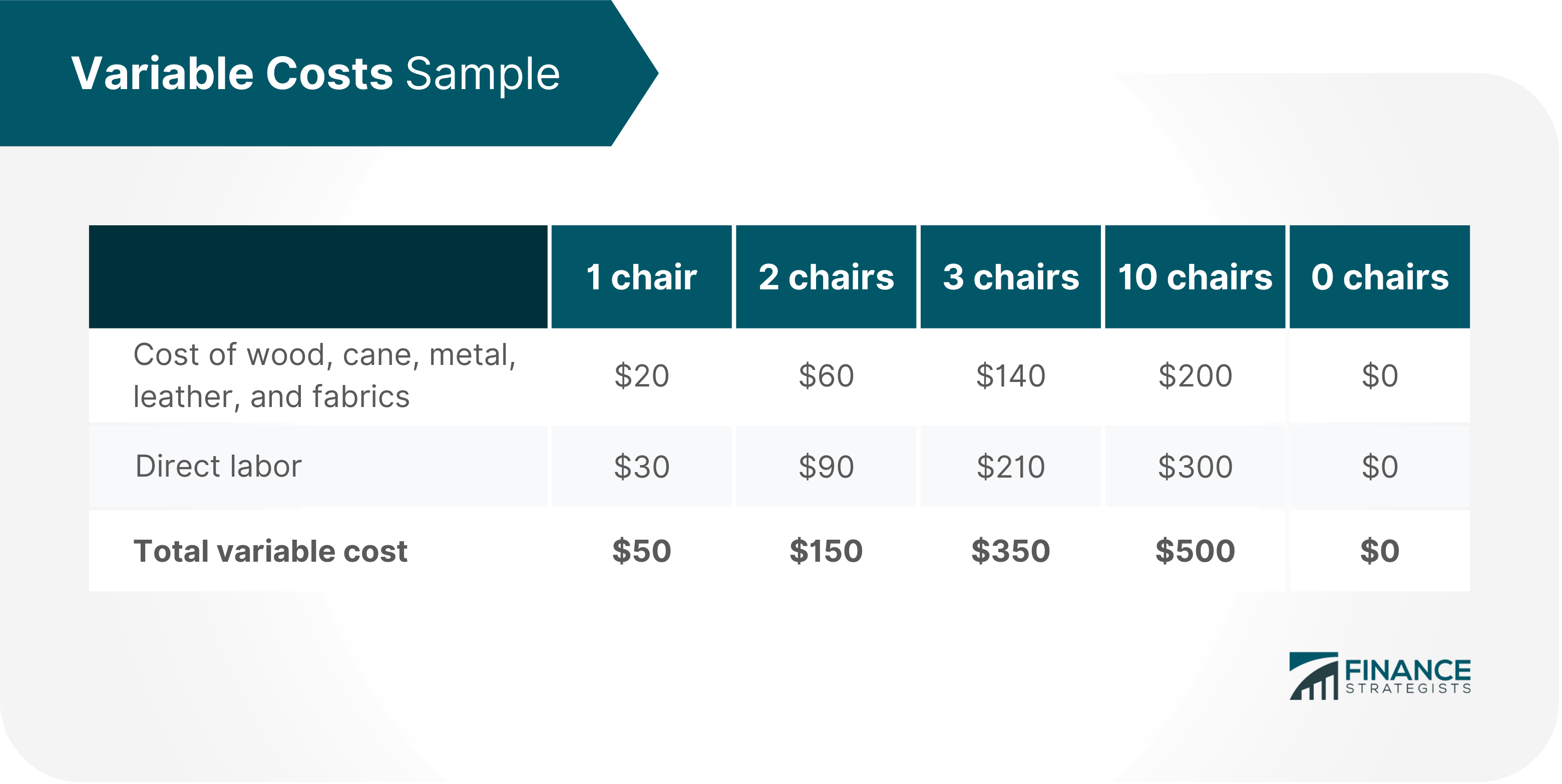

- Variable costs . These expenses depend on the amount of production or sales made within a given period, such as raw materials used for making products. For example, it costs a furniture shop $50 to make a chair—$20 for raw materials such as wood, cane, metal, leather, and fabrics, and $30 for the direct labor involved in making one chair.

Below shows how the variable costs change as the number of chairs made varies.

As the production output of chairs increases, the bakery’s variable costs also increase. When the furniture shop does not make any chair, its variable costs drop to zero.

- Indirect costs . These are expenses that cannot be directly linked to the making or selling of goods or services, such as administrative salaries, office expenses, security expenses, and utilities.

- Direct Costs. These are costs that can be directly linked to the making or selling of goods or services. For example, if a company pays for equipment rental to produce their product, this cost is considered direct because it links back to how many units have been produced.

Why Is Cost Allocation Important?

Cost allocation is an important part of any business. The following points reflect why you should always be sure to allocate all your expenses:

- It helps in accurate decision-making. When costs are known, it is easier to determine which strategies will most benefit the business or individual.

- Allocating cost enables comparison between different products and services.

For example, comparing the cost of producing one product versus another can help decide which should be produced more often based on its profitability compared with other goods or services offered by a company.

- It helps in understanding which departments are more profitable than others. Identifying the cost of different areas of business allows for better decision-making at the departmental level, and overall.

- It can help identify problem areas within a company to allow for improvements or changes that might be beneficial for future production or sales.

Taking these factors into account when allocating cost allows businesses and individuals to understand better how much money they need coming in (revenue) compared with how much they must spend (costs).

This makes setting prices easier since there is an understanding of what each unit sold brings in revenue-wise.

Common Mistakes People Make When Allocating Costs

- Not accounting for overhead . Overhead is a general term that refers to indirect expenses, which are not directly attributed to the cost of goods sold (COGS) or fixed costs.

- Not taking into account which projects are currently generating revenue and which ones aren’t.

- Not allocating indirect expenses equally among departments and projects within a company.

- Not considering how fluctuating revenue affects indirect expenses. If you’re seeing a lot of variability in revenue over time, you need to account for that when allocating costs.

- Using the incorrect allocation method. There are many different methods for allocating costs and using more than one can help you get a better idea of where your business is spending its money.

Process of Cost Allocation

The following is an overview of how to allocate costs and some tips on what you should take into consideration when doing so.

Step One: Identify Your Costs

The first step is to identify all of your costs. This includes both direct and indirect expenses, as well as fixed or variable costs.

Step Two: Allocate Indirect Costs Between Departments or Products

Indirect costs should be allocated between departments, projects, and products based on a fair allocation plan that reflects their use in those areas.

For example, suppose your company produces two products, products A and B.

In that case, you will need to construct a cost-allocation plan that reflects the allocation of overhead expenses between these areas.

Step Three: Allocate Fixed Costs Among Departments or Projects

Fixed costs are allocated among departments or projects based on how they benefit each area.

For example, if Product A produces a specific product that is used for Product B, it would be appropriate to allocate the fixed costs associated with producing Product A between these two products.

Step Four: Allocate Variable Costs Among Departments or Projects

Variable costs are allocated among departments or projects based on how much of each cost driver they use.

For example, if your company produces two products, A and B (and each product has its own direct labor cost), you would first need to determine how many units of Product A are produced for every unit of Product B sold.

You can then use this information to allocate the variable costs associated with producing each product based on their respective rates.

Step Five: Use Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis to Determine the Best Allocation Method

If your company uses multiple products, services, or departments that incur indirect costs, cost allocation is important in determining which method will work best for reporting profits accurately.

For example, suppose you’re using a full absorption costing (FAC) system and another department within your company is using a direct labor cost system.

In that case, you may need to use more than one allocation method.

Step Six: Use Cost Allocation for Decision Making & Reporting

Cost allocation is important for both decision-making and reporting purposes.

Using cost allocation, you can determine which areas of your company are over or under-spending and how changes to specific processes will affect the overall profitability of a product or department.

Common Cost Allocation Methods

Cost allocation faqs, what is cost allocation.

Cost allocation is the process of assigning expenses to one or more cost objects. A cost object can be a product, project, department, business unit, or another grouping within an organization with costs associated with it.

How is cost allocation done?

There are many ways to allocate expenses, including the high/low method and step-up/down. There’s also a simple way called the direct materials cost method that uses an allocation base of the same value as the variable rate. Using FAC or Variable costing can provide more accurate reporting on your company’s financials.

What are the benefits of cost allocation?

Cost allocation allows you to determine where costs can be reduced and provides accurate reporting on company financials based on its relative performance. Allocating indirect expenses is also important for decision-making purposes. With this information, you can determine which areas of your business need improvement and how changes in production will affect overall profitability. Cost allocation can also show you which departments or products are spending too much money on indirect expenses, and which ones aren’t using enough of them. This enables you to make more informed staffing decisions in the future based on how your company’s needs change over time. Finally, cost allocation allows companies to compare their performance against similar businesses.

What are common mistakes people make when allocating costs?

One of the most common mistakes is to allocate indirect expenses based on current production volume. Other issues include not performing cost allocation at all or using arbitrary rates rather than industry standards. When deciding how to allocate these types of expenses, companies should consider their company’s size and what it will cost to produce a certain amount of output.

How is cost allocation performed?

Cost allocation can be done manually or through software. It’s important to keep detailed records of all your company’s expenses so you have accurate financial reports for decision-making purposes. If you don’t have cost records, the process of allocation can be time-consuming and difficult to determine. You may not know which department or product each expense is associated with, so your reports will lack accuracy.

About the Author

True Tamplin, BSc, CEPF®

True Tamplin is a published author, public speaker, CEO of UpDigital, and founder of Finance Strategists.

True is a Certified Educator in Personal Finance (CEPF®), author of The Handy Financial Ratios Guide , a member of the Society for Advancing Business Editing and Writing, contributes to his financial education site, Finance Strategists, and has spoken to various financial communities such as the CFA Institute, as well as university students like his Alma mater, Biola University , where he received a bachelor of science in business and data analytics.

To learn more about True, visit his personal website or view his author profiles on Amazon , Nasdaq and Forbes .

Related Topics

- Cost Allocation Base

- Cost Application

Ask a Financial Professional Any Question

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.

Fact Checked

At Finance Strategists, we partner with financial experts to ensure the accuracy of our financial content.

Our team of reviewers are established professionals with decades of experience in areas of personal finance and hold many advanced degrees and certifications.

They regularly contribute to top tier financial publications, such as The Wall Street Journal, U.S. News & World Report, Reuters, Morning Star, Yahoo Finance, Bloomberg, Marketwatch, Investopedia, TheStreet.com, Motley Fool, CNBC, and many others.

This team of experts helps Finance Strategists maintain the highest level of accuracy and professionalism possible.

Why You Can Trust Finance Strategists

Finance Strategists is a leading financial education organization that connects people with financial professionals, priding itself on providing accurate and reliable financial information to millions of readers each year.

We follow strict ethical journalism practices, which includes presenting unbiased information and citing reliable, attributed resources.

Our goal is to deliver the most understandable and comprehensive explanations of financial topics using simple writing complemented by helpful graphics and animation videos.

Our writing and editorial staff are a team of experts holding advanced financial designations and have written for most major financial media publications. Our work has been directly cited by organizations including Entrepreneur, Business Insider, Investopedia, Forbes, CNBC, and many others.

Our mission is to empower readers with the most factual and reliable financial information possible to help them make informed decisions for their individual needs.

How It Works

Step 1 of 3, ask any financial question.

Ask a question about your financial situation providing as much detail as possible. Your information is kept secure and not shared unless you specify.

Step 2 of 3

Our team will connect you with a vetted, trusted professional.

Someone on our team will connect you with a financial professional in our network holding the correct designation and expertise.

Step 3 of 3

Get your questions answered and book a free call if necessary.

A financial professional will offer guidance based on the information provided and offer a no-obligation call to better understand your situation.

Where Should We Send Your Answer?

Just a Few More Details

We need just a bit more info from you to direct your question to the right person.

Tell Us More About Yourself

Is there any other context you can provide.

Pro tip: Professionals are more likely to answer questions when background and context is given. The more details you provide, the faster and more thorough reply you'll receive.

What is your age?

Are you married, do you own your home.

- Owned outright

- Owned with a mortgage

Do you have any children under 18?

- Yes, 3 or more

What is the approximate value of your cash savings and other investments?

- $50k - $250k

- $250k - $1m

Pro tip: A portfolio often becomes more complicated when it has more investable assets. Please answer this question to help us connect you with the right professional.

Would you prefer to work with a financial professional remotely or in-person?

- I would prefer remote (video call, etc.)

- I would prefer in-person

- I don't mind, either are fine

What's your zip code?

- I'm not in the U.S.

Submit to get your question answered.

A financial professional will be in touch to help you shortly.

Part 1: Tell Us More About Yourself

Do you own a business, which activity is most important to you during retirement.

- Giving back / charity

- Spending time with family and friends

- Pursuing hobbies

Part 2: Your Current Nest Egg

Part 3: confidence going into retirement, how comfortable are you with investing.

- Very comfortable

- Somewhat comfortable

- Not comfortable at all

How confident are you in your long term financial plan?

- Very confident

- Somewhat confident

- Not confident / I don't have a plan

What is your risk tolerance?

How much are you saving for retirement each month.

- None currently

- Minimal: $50 - $200

- Steady Saver: $200 - $500

- Serious Planner: $500 - $1,000

- Aggressive Saver: $1,000+

How much will you need each month during retirement?

- Bare Necessities: $1,500 - $2,500

- Moderate Comfort: $2,500 - $3,500

- Comfortable Lifestyle: $3,500 - $5,500

- Affluent Living: $5,500 - $8,000

- Luxury Lifestyle: $8,000+

Part 4: Getting Your Retirement Ready

What is your current financial priority.

- Getting out of debt

- Growing my wealth

- Protecting my wealth

Do you already work with a financial advisor?

Which of these is most important for your financial advisor to have.

- Tax planning expertise

- Investment management expertise

- Estate planning expertise

- None of the above

Where should we send your answer?

Submit to get your retirement-readiness report., get in touch with, great the financial professional will get back to you soon., where should we send the downloadable file, great hit “submit” and an advisor will send you the guide shortly., create a free account and ask any financial question, learn at your own pace with our free courses.

Take self-paced courses to master the fundamentals of finance and connect with like-minded individuals.

Get Started

To ensure one vote per person, please include the following info, great thank you for voting., get in touch, submit your info below and someone will get back to you shortly..

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, cost allocation: what purpose does it serve.

Managerial Auditing Journal

ISSN : 0268-6902

Article publication date: 1 November 1996

Regardless of the approach taken to allocating common costs, is cost allocation really necessary? Argues that such an exercise may not make any difference to the final outcome ‐ the company’s final profit or loss figure. Takes as an example the University of Clemson, USA’s system of costing and reporting, and describes the university’s Finance Committee’s challenge to that system.

- Cost allocation

- Financial statements

- Universities

Doost, R.K. (1996), "Cost allocation: what purpose does it serve?", Managerial Auditing Journal , Vol. 11 No. 8, pp. 14-22. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686909610131648

Copyright © 1996, MCB UP Limited

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

- Cost Classifications

- Relevant Cost of Material

- Manufacturing Overhead Costs

- Conversion Costs

- Quality Costs

- Revenue Expenditure

- Product Cost vs Period Cost

- Direct Costs and Indirect Costs

- Prime Costs and Conversion Costs

- Relevant vs Irrelevant Costs

- Avoidable and Unavoidable Costs

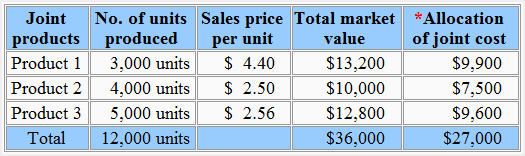

- Cost Allocation

- Joint Products

- Accounting for Joint Costs

- Service Department Cost Allocation

- Repeated Distribution Method

- Simultaneous Equation Method

- Specific Order of Closing Method

- Direct Allocation Method

Cost allocation is the process by which the indirect costs are distributed among different cost objects such as a project, a department, a branch, a customer, etc. It involves identifying the cost object, identifying and accumulating the costs that are incurred and assigning them to the cost object on some reasonable basis.

Cost allocation is important for both pricing and planning and control decisions. If costs are not accurately calculated, a business might never know which products are making money and which ones are losing money. If cost are mis-allocated, a business may be charging wrong price to its customers and/or it might be wasting resources on products that are wrongly categorized as profitable.

Cost allocation is a sub-process of cost assignment , which is the overall process of finding total cost of a cost object. Cost assignment involves both cost tracing and cost allocation. Cost tracing encompasses finding direct costs of a cost object while the cost allocation is concerned with indirect cost charge.

Steps in cost allocation process

Typical cost allocation mechanism involves:

- Identifying the object to which the costs have to be assigned,

- Accumulating the costs in different pools,

- Identifying the most appropriate basis/method for allocating the cost.

Cost object

A cost object is an item for which a business need to separately estimate cost.

Examples of cost object include a branch, a product line, a service line, a customer, a department, a brand, a project, etc.

A cost pool is the account head in which costs are accumulated for further assignment to cost objects.

Examples of cost pools include factory rent, insurance, machine maintenance cost, factory fuel, etc. Selection of cost pool depends on the cost allocation base used. For example if a company uses just one allocation base say direct labor hours, it might use a broad cost pool such as fixed manufacturing overheads. However, if it uses more specific cost allocation bases, for example labor hours, machine hours, etc. it might define narrower cost pools.

Cost driver

A cost driver is any variable that ‘drives’ some cost. If increase or decrease in a variable causes an increase or decrease is a cost that variable is a cost driver for that cost.

Examples of cost driver include:

- Number of payments processed can be a good cost driver for salaries of Accounts Payable section of accounting department,

- Number of purchase orders can be a good cost driver for cost of purchasing department,

- Number of invoices sent can be a good cost driver for cost of billing department,

- Number of units shipped can be a good cost driver for cost of distribution department, etc.

While direct costs are easily traced to cost objects, indirect costs are allocated using some systematic approach.

Cost allocation base

Cost allocation base is the variable that is used for allocating/assigning costs in different cost pools to different cost objects. A good cost allocation base is something which is an appropriate cost driver for a particular cost pool.

T2F is a university café owned an operated by a student. While it has plans for expansion it currently offers two products: (a) tea & coffee and (b) shakes. It employs 2 people: Mr. A, who looks after tea & coffee and Mr. B who prepares and serves shakes & desserts.

Its costs for the first quarter are as follows:

| Mr. A salary | 16,000 |

| Mr. B salary | 12,000 |

| Rent | 10,000 |

| Electricity | 8,000 |

| Direct materials consumed in making tea & coffee | 7,000 |

| Direct raw materials for shakes | 6,000 |

| Music rentals paid | 800 |

| Internet & wi-fi subscription | 500 |

| Magazines | 400 |

Total tea and coffee sales and shakes sales were $50,000 & $60,000 respectively. Number of customers who ordered tea or coffee were 10,000 while those ordering shakes were 8,000.

The owner is interested in finding out which product performed better.

Salaries of Mr. A & B and direct materials consumed are direct costs which do not need any allocation. They are traced directly to the products. The rest of the costs are indirect costs and need some basis for allocation.

Cost objects in this situation are the products: hot beverages (i.e. tea & coffee) & shakes. Cost pools include rent, electricity, music, internet and wi-fi subscription and magazines.

Appropriate cost drivers for the indirect costs are as follows:

| Rent | 10,000 | Number of customers |

| Electricity | 8,000 | United consumed by each product |

| Music rentals paid | 800 | Number of customers |

| Internet & wifi subscription | 500 | Number of customers |

| Magazines | 400 | Number of customers |

| 19,700 |

Since number of customers is a good cost driver for almost all the costs, the costs can be accumulated together to form one cost pool called manufacturing overheads. This would simply the cost allocation.

Total manufacturing overheads for the first quarter are $19,700. Total number of customers who ordered either product are 18,000. This gives us a cost allocation base of $1.1 per customer ($19,700/18,000).

A detailed cost assignment is as follows:

| Tea & Coffee | Shakes | |

| Revenue | 50,000 | 60,000 |

| Costs: | ||

| Salaries | 16,000 | 12,000 |

| Direct materials | 7,000 | 6,000 |

| Manufacturing overheads allocated | 11,000 | 8,800 |

| Total costs | 34,000 | 26,800 |

| Profit earned | 16,000 | 33,200 |

Manufacturing overheads allocated to Tea & Cofee = $1.1×10,000

Manufacturing overheads allocated to Shakes = $1.1×8,000

by Irfanullah Jan, ACCA and last modified on Jul 22, 2020

Related Topics

- Cost Behavior

All Chapters in Accounting

- Intl. Financial Reporting Standards

- Introduction

- Accounting Principles

- Business Combinations

- Accounting Cycle

- Financial Statements

- Non-Current Assets

- Fixed Assets

- Investments

- Revenue Recognition

- Current Assets

- Receivables

- Inventories

- Shareholders' Equity

- Liability Accounts

- Accounting for Taxes

- Employee Benefits

- Accounting for Partnerships

- Financial Ratios

- Cost Accounting Systems

- CVP Analysis

- Relevant Costing

- Capital Budgeting

- Master Budget

- Inventory Management

- Cash Management

- Standard Costing

Current Chapter

XPLAIND.com is a free educational website; of students, by students, and for students. You are welcome to learn a range of topics from accounting, economics, finance and more. We hope you like the work that has been done, and if you have any suggestions, your feedback is highly valuable. Let's connect!

Copyright © 2010-2024 XPLAIND.com

Article Categories

Book categories, collections.

- Business, Careers, & Money Articles

- Business Articles

- Accounting Articles

- General Accounting Articles

The Step-Down Allocation Method in Cost Accounting

Cost accounting for dummies.

Sign up for the Dummies Beta Program to try Dummies' newest way to learn.

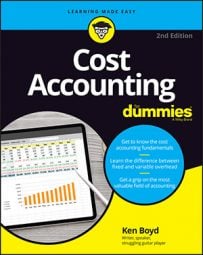

When cost accounting, the step-down allocation method allows support departments to allocate costs to each other — and ultimately to the operating departments. To accomplish this, the support departments are ranked. The ranking is often based on the percentage of costs that a support department incurs to support other support departments.

The support department with the highest percentage is allocated first. All of its costs are allocated out — whether to an operating department or to another support department. After that, the support department with the second-highest percentage is allocated. Step by step, the costs for each support department are fully allocated. In the end, the calculation “goes flat,” because all costs are allocated.

Your company has both a human resources (HR) department and a legal department which support two operating departments: assembly and shipping. Say $10,000 of the human resources cost is allocated to the legal department. Legal doesn’t allocate any costs to human resources. So you rank the HR department higher than legal. That’s because HR allocates support costs to another support department and legal doesn’t. This table shows that allocation.

| Legal | Assembly | Shipping | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beginning balance | $300,000 | $1,000,000 | $75,000 | |

| HR cost allocation | ||||

| $100,000 | $10,000 | $10,000 | $80,000 | $10,000 |

| $200,000 + $10,000 | $189,000 | $21,000 | ||

| Total allocation | -$310,000 | $269,000 | $31,000 | |

All good, except there’s a drawback. This allocation method doesn’t allow costs to be allocated between multiple support departments. For example, what if legal also provides services to the HR department? When you rank the support departments and allocate out the costs, you can’t allocate costs back in.

About This Article

This article is from the book:.

- Cost Accounting For Dummies ,

About the book author:

Kenneth W. Boyd has 30 years of experience in accounting and financial services. He is a four-time Dummies book author, a blogger, and a video host on accounting and finance topics.

This article can be found in the category:

- General Accounting ,

- Cost Accounting For Dummies Cheat Sheet

- Must Know Formulas for Cost Accounting

- Important Terms and Principles Cost Accountants Should Know

- Avoiding Pitfalls on Cost Accounting Exams

- Accrual Accounting in Cost Accounting

- View All Articles From Book

Close Management

Reconciliation Automation

Connected Compliance

Accounting Operations

Accounting Automation Platform

Scalability & Usability

Integrations

Accounting Manager

Internal Audit Manager

Success Stories

Video Testimonials

Partner Program

Become a Partner

All Resources

FloQast Blog

Checklists & Templates

Customer Video Testimonials

Whitepapers

Customer Success Stories

FloQast Studios

Services & Support

Customer Success Management

Request Support

Professional Education & Training Courses

FloQademy - Join/Sign in

The FloQast Advantage

What is Cost Allocation? Definition & Process

Jul 16, 2020 Michael Whitmire

Working with the former accountants now working at FloQast, we decided to take a look at some of the pillars of the accounting professions.

The key to running a profitable enterprise of any kind is making sure that your prices are high enough to cover all your costs — and leave at least a bit for profit. For a really simple business — like the proverbial lemonade stand that almost every kid ran — that’s pretty simple. Your costs are what you (or your parents) paid for lemons and sugar. But what if it’s a more complex business? Then you might need to brush up on cost accounting, and learn about allocation accounting . Let’s walk through this using the hypothetical company, Lisa’s Luscious Lemonade.

What is cost allocation ?