WhatsApp: +44-7360-275888

- No products in the cart.

Assignment based learning

Lsbr's unique approach to learning, unique assessment strategy.

London School of Business and Research (LSBR) , Assessment Strategy includes Assignment based learning.

Assignments and assessment are important aspects of learning. Completing an assignment is an opportunity to demonstrate your achievement. Feedback on assignments provides you with measurement of your achievement in relation to the standards set by the course and the college.

To ensure that all students have equal opportunities to demonstrate what they can do, and to receive accurate and useful feedback on their work, London School of Business and Research (LSBR) has devised this Assignments and Assessment Policy, which sets out what is required and expected of both students and staff.

User registration

You don't have permission to register, reset password.

- Have any questions ?

- +971 552272114

- [email protected]

- Links with the Industry

- Our Partners

- Online Executive MBA - CMU

- MBA – Strategic Management & Leadership - CMU

- MBA International - CCCU

- MBA International (Top- up)

- MBA - University of Gloucestershire (GLOS)

- MBA with Global Business Administration (GLOS)

- MBA with Global Business Administration with Marketing Intelligence and Big Data (GLOS)

- MBA with Global Business Administration with Cyber Governance and Digital Transformation (GLOS)

- MBA with Global Business Administration with Financial Services Management (GLOS)

- MBA with Global Business Administration with Applied Entrepreneurship, Design Thinking and Innovation (GLOS)

- MBA in Global Business Administration with International Tourism and Hospitality Management (GLOS)

- MBA with Supply Chain Management - Abertay University

- MBA with Healthcare Management - Abertay University

- MBA with HR and Organizational Psychology - Abertay University

- MBA with Finance and Risk Management - Abertay University

- MBA with Engineering Management - Abertay University

- MBA with Information Technology - Abertay University

- MBA with Educational Leadership - Abertay University

- MBA with Health and Safety Leadership - Abertay University

- MBA with Management of Public Health

- MBA with Cyber Governance and Law - Abertay University

- MBA with Entrepreneurship & Innovation - Abertay University

- MBA with Business Analytics - Abertay University

- MBA with Operations and Project Management - Abertay University

- MBA with Marketing Intelligence & Big data - Abertay University

- MBA with Sales and Marketing - Abertay University

- Executive MBA in HR Management and Analytics - UCAM

- Executive MBA in Business Operations

- Executive MBA in Logistics and Supply Chain Leadership - UCAM

- Executive MBA in Global Business Management - UCAM

- Executive MBA in Engineering Management - UCAM

- Executive MBA in Healthcare Leadership - UCAM

- Executive MBA in Information Technology Leadership - UCAM

- MBA with Sales & Marketing - UCAM

- MBA with Specialization - Girne American University

- CMI L7 Strategic Management and Leadership Practice

- MSc Digital Marketing and e-Business

- MSc Accounting and Finance (CIMA Gateway)

- MSc. Construction and Project Management

- Masters in Data Science and Artificial Intelligence (AI)

- BSc (Hons) Business with International Business Management (LJMU)

- BSc (Hons) Business with Finance (LJMU)

- BSc (Hons) Business with Digital Marketing (LJMU)

- BSc (Hons) Computer Science - LJMU

- BSc (Hons) Business Psychology with Human Resource Management - LJMU

- BA (Hons) in Fashion: Design and Communication - LJMU

- BA (Hons) Media, Culture and Communication - LJMU

- BA (Hons) Sports Business - LJMU

- BSc (Hons) Business Management - CCCU

- BA (Hons) Accounting and Finance - GLOS

- BA (Hons ) Business Management - ABERTAY

- BA (Hons) Business Management with Business Analytics - ABERTAY

- BA (Hons) in Business with Digital Marketing - Abertay University

- BA (Hons) in Business with Finance - Abertay University

- Doctorate of Business Administration - UCAM

- Doctorate of Business Administration - Abertay University

- Postgraduate Diploma in Procurement & Contract Management

- Postgraduate Diploma in Sales & Marketing Management

- Postgraduate Diploma in Supply Chain Management and Logistics

- Postgraduate Diploma in Healthcare Management and Leadership

- Postgraduate Diploma in Tourism and Hospitality Management

- Postgraduate Diploma in Human Resource Management | HRM

- Postgraduate Diploma in Finance & Risk Management

- Postgraduate Diploma in Engineering Management

- Postgraduate Diploma in Project Management

- Certificate in Strategic Management and Leadership Practice

- CMI Programs

- Diploma in Business Psychology

- Diploma in Fashion Illustration

- Diploma in Supply Chain and Logistics Management

- Diploma in Business Analytics

- Diploma in Information Technology

- Diploma in Finance and Risk Management

- Diploma in Business Management

- Diploma in Fashion Design

- Diploma in Healthcare Management and Leadership

- Diploma in Business Finance

- Diploma in Digital Marketing

- Diploma in Operations and Project Management

- Diploma in Engineering Management

- Diploma in Human Resources & Organizational Culture

- Diploma in Computing

- Diploma in Film and Media

- Diploma in Sports Management

- ACCA – Association Chartered Certified Accountants

- Higher National Diploma in Art and Design (Fashion)

- Higher National Diploma in Computing

- HND in Counselling and Applied Psychology

- Higher National Diploma In Business

- Higher National Diploma in Sport

- BTEC Level 3 National Foundation Diploma in Business

- Master of Arts in Leadership in Education

- Master of Arts in Education

- Postgraduate Certificate in Education (International) - LJMU

- Postgraduate Certificate in Education International (PGCEi)

- Notable Westford Alumni

- Student Interview

- DBA Candidates

- Research Journals

- Humans Of Westford

- MBA Decoded

- Mentorship program

- International Immersion Program

- Toastmaster Club

- Accommodation Partner- Nest

- International Student Research Conference (ISRC)

- International Faculty Research Conference (IFRC)

- Student Recruitment Drive

- Westford for Business

- August 5, 2020

- Management Articles

- 3 Minutes Read

Assignment based evaluation Vs Exam based evaluation for management programs – Merits for Executive MBA students

Assignment and examination-based evaluation are two of the most common assessment methods for evaluating the progress of students in their learning. Moreover, the essential purpose of evaluating student learning is to determine whether the students are achieving the learning outcomes laid out for them.

Assignment based evaluation Vs Exam based evaluation

Now the big question is, which one is more effective? An assignment-based evaluation or an exam-based evaluation.

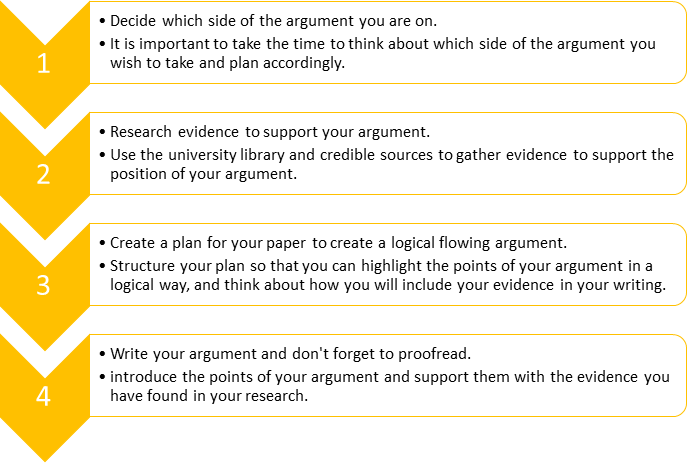

Research and records indicate that, over the last 40 years in the United Kingdom and other nations, the assignment-based evaluation or completion of the module assessment of higher education coursework (postgraduate, Master’s & Ph.D.) has significantly enhanced. This has been exemplified in numerous academic research articles. It is likewise recognized that a higher proportion of learners themselves chose to be assessed along with the basis of coursework or assignment. The study also shows that the assignment-based assessment continues to yield a better score than the examination alone. A well-known researcher on this subject in 2015, John T.E. Richardson, found that student examination-based performance is more common. In its conclusions, the researcher emphasized the lack of feedback in an examination-based appraisal and its deficiency in the proper evaluation of the scope and depth of learning per se. The researcher also reasoned that, rather than promoting successful learning, an exam-based assessment merely measures knowledge at the particular moment, it means that the student’s examination experience does not make a reasonable contribution to learning compared to the way the assignment-based evaluation does. However, the review-based evaluation cannot be rejected; a blended methodology can be implemented. The evaluation of the coursework has to be given more attention because it provides students with a stronger learning experience.

Advantages of Assignment based evaluation

Needless to mention, assignment-based assessments can encourage higher teaching and learning experiences for students to think critically, develop new perspectives, resolve problems, navigate incidents, and ask the right questions. The project results in better learning skills for students in general. Here are some of the distinct benefits of assignment-based evaluation:

- Enhances cognitive and analytical capabilities – The rational reasoning of students is strengthened. They will get the opportunity to exercise and develop their mental and innovative ability. Assignments offer students a chance to experiment while becoming unconventional. It offers students the ability to be more productive and flexible.

- Learners become research-oriented – Through their assignments, students are required to carry out an in-depth study of their specific topic. By doing so, they are throwing out different theories and exploring their subject. Research on their assignment experience also enhances the student’s practical and thought-provoking skills at a professional level.

- Increases cognizance and understanding about the topic — Assignments allow students to understand the technical and practical information about their subject that they cannot completely grasp in theory. Students become more aware of various insightful principles and perspectives through their coursework, which ultimately leads to the rational development of a framework for their topic.

- Improves the technical writing skills – Students are likewise expected to compose their assignments in the form of reports and on a certain study or scenario. The writing skills and talents are strengthened in this way. In the long term, students can articulate their thoughts and ideas more efficiently.

At Westford University College (WUC), we have implemented an assessment-based evaluation approach to assess the learning of our students. We periodically assess our MBA students with assigned coursework (assignment) to read their writing and work skills, discernment of the subject, and overall success in their course. We assume that high quality and equal evaluation are important to the development of effective learning.

Related Links

Virtual Learning: Merits and Demerits

How to convert a Junior level career to Managerial level ?

Top 10 Executive MBA Programs in the World | Top 10 Business Schools

get in touch

Phone Number

Latest Blogs

Financial Voyage: Pioneering Your Career with an Accounting & Finance Program

PGCEi Virtual Open Day: A Gateway to Transformative Teaching

Safeguarding Success: Unlocking the Power of Occupational Health and Safety in the Workplace

Transformative Power of Internships during your bachelor’s Program

Transforming Decision-Making Through Big Data

Established in 2009, The Westford University College is the most trusted executive educational institution in UAE, providing flexible learning and affordable programs for regular students and working professionals (Perfect ‘Work-Life-Study’ Balance). We provide top rated MBA Programs, Bachelors Courses, Professional Programs and corporate training. 13300+ students, 80+ Courses, 130+ Nationalities, 20+ Academic Partners, 14+ years in the market.

Our Student Base

Mba programs.

- Cardiff Met MBA (Advanced Entry)

- MBA – Cardiff Metropolitan University

- MBA – Healthcare Management

- MBA – Supply Chain and Logistics Management

- MBA – Engineering Management

- MBA – Information Technology

- MBA – HR & Organizational Psychology

- MBA – Project Management

- MBA – International

- MBA - University of Gloucestershire

- MBA with Specialization - GAU

- MBA – Education Leadership

- UCAM MBA Executive

Bachelors Programs

- BSc (Hons) in Business with Finance

- BSc (Hons) in Business with Digital Marketing

- BSc (Hons) in Business with International Business

- BA (Hons) in Media, Culture and Communication

- BSc (Hons) in Business Psychology with Human Resource Management

Diploma Coures

- Diploma in Business Finance

- Diploma in Human Resources & Organizational Culture

- PG Diploma in Engineering Management

- PG Diploma in Retail Management

- PG Diploma in Sales & Marketing Management

- HND in Art and Design

- HND in Computing

Other Programs

- Teacher Training

Ready to get started ? Talk to us today

Al Taawun Campus Tejara 3, Al Taawun, Sharjah, UAE

Westford University College | Masters Degree | Under Graduate Degree | Diploma Courses | Certificate Courses | Corporate Training | Management Programs

- Privacy Policy

- Anti-Bribery & Corruption Policy

- Data Protection Policy

- Equality & Diversity Policy

- Environmental Policy

- Refund Policy

Thank you for showing interest in SNATIKA Programs.

Our Career Guides would shortly connect with you.

For any assistance or support, please write to us at info@snatika.com

You have already enquired for this program. We shall send you the required information soon.

- +234 1 8880 209 +27 21 825 9877 + 1 347 855 4980 + 44 20 3287 6900

- info@snatika.com

Strategic Management and Leadership (MBA)

Business Administration (MBA )

Project Management (MBA)

Risk Management (MBA)

Oil & Gas Management (MBA)

Engineering Management (MBA)

Facilities Management (MBA)

Project Management (MSc)

Risk Management (MSc)

Business Management & Strategy (BA Hons)

Business Administration (BBA)

Strategic Management & Leadership Practice (Level 8)

Strategic Management & Leadership (Level 8)

Diploma in Quality Management ( Level 7)

Diploma in Operations Management (Level 7)

Diploma for Construction Senior Management (Level 7)

Diploma in Strategic Management and Innovation (Level 7)

Diploma in Management Consulting (Level 7)

Diploma in Executive Management (Level 7)

Diploma in Business Management (Level 6)

Certificate in Security Management (Level 5)

Diploma in Strategic Management Leadership (Level 7)

Diploma in Project Management (Level 7)

Diploma in Risk Management (Level 7)

Finance (MBA)

Accounting and Finance (MSc)

Accounting & Finance (MBA)

Accounting and Finance (BA)

Diploma in Asset-based Lending (Level 7)

Diploma in Accounting and Business (Level 6)

Diploma in Wealth Management (Level 7)

Diploma in Capital Markets, Regulations, and Compliance (Level 7)

Certificate in Financial Trading (Level 6)

Diploma in Accounting Finance (Level 7)

Education Management (MBA)

Coaching and Mentoring (MBA)

Education Management and Leadership (MA)

Coaching and Mentoring (MA)

Diploma in Education and Training (Level 5)

Diploma in Early Learning and Childcare (Level 5)

Diploma in Teaching and Learning (Level 6)

Diploma in Translation (Level 7)

Diploma in Career Guidance & Development (Level 7)

Certificate in Research Methods (Level 7)

Diploma in Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for Leadership (Level 7)

Certificate in Academic and Professional Skills Development (Level 6)

Certificate in Leading the Internal Quality Assurance of Assessment Processes and Practice (Level 4)

Diploma in Education Management Leadership (Level 7)

Diploma in Coaching Mentoring (Level 7)

Health & Safety Management (MBA)

Health and Social Care Management (MBA)

Health and Social Care Management (MSc)

Diploma in Psychology (Level 5)

Diploma in Health and Wellness Coaching (Level 7)

Diploma in Health and Social Care Management (Level 6)

Diploma in Health Social Care Management (Level 7)

Human Resource Management (MBA)

Human Resources Management (MA)

Human Resources Management (MSc)

Diploma in Human Resource Management (Level 7)

Cyber Security (MBA)

Data Science (MBA)

Information Technology (BSc Hons)

Cyber Security (BSc Hons)

Diploma in Data Science (Level 7)

Diploma in Cyber Security (Level 5 & Level 4)

Diploma in Information Technology (Level 6)

Diploma in IT - E-commerce (Level 5 & Level 4)

Diploma in IT - Networking (Level 5 & Level 4)

Diploma in IT - Web Design (Level 5 & Level 4)

International Law (MBA)

International Law (LLM)

Certificate in Paralegal (Level 7)

Diploma in International Business Law (Level 7)

Shipping Management (MBA)

Logistics and Supply Chain Management (MBA)

Logistics and Supply Chain Management (MSc)

Diploma in Procurement and Supply Chain Management (Level 7)

Diploma in Logistics and Supply Chain Management (Level 6)

Diploma in Logistics Supply Chain Management (Level 7)

Marketing (MBA)

Strategic Marketing (MSc)

Diploma in Brand Management (Level 7)

Diploma in Digital Marketing (Level 7)

Diploma in Professional Marketing (Level 6)

Diploma in Strategic Marketing (Level 7)

Public Administration (MBA)

Public Administration (MA)

Police Leadership And Management (MSc)

Diploma in International Trade (Level 7)

Certificate in Public Relations ( Level 4)

Diploma in International Relations (Level 7)

Diploma in Public Administration (Level 7)

Diploma in Police Leadership Management (Level 7)

Tourism & Hospitality Management (MBA)

Tourism & Hospitality (MBA)

Tourism and Hospitality Management (MSc)

Tourism & Hospitality (BA)

Diploma in Facilities Management (Level 7)

Diploma in Tourism & Hospitality Management (Level 6)

Certificate in Golf Club Management (Level 5)

Diploma in Tourism Hospitality Management (Level 7)

- Learner Stories

- Recruitment Partner

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

All Doctorate Programs

- Doctorate Program in Strategic Management and Leadership Practice - OTHM - Level 8

- Doctorate Program in Strategic Management and Leadership - QUALIFI - Level 8

All Masters Programs

- Masters Program in Strategic Management and Leadership - LGS - MBA

- Masters Program in Strategic Management and Leadership - UOG - MBA

- Masters Program in Project Management - LGS - MSc

- Masters Program in Risk Management - LGS - MSc

- Masters Program in Business Administration - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Risk Management - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Project Management - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - EIE - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Oil & Gas Management - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Engineering Management - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Facilities Management - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Shipping Management - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Strategic Management and Leadership – ARDEN UNIVERSITY – MBA

- Masters Program in Accounting and Finance - LGS - MSc

- Masters Program in Accounting and Finance - UOG - MSc

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Finance - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Accounting & Finance - EIE - MBA

- Masters Program in Accounting and Finance - ARDEN UNIVERSITY - MSc

- Masters Program in Coaching and Mentoring - LGS - MA

- Masters Program in Education Management and Leadership - LGS - MA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Education Management - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Coaching & Mentoring - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Health and Social Care Management - LGS - MSc

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Health & Social Care Management - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Health & Safety Management - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Human Resources Management - LGS - MA

- Masters Program in Human Resources Management - UOG - MSc

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Human Resource Management - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in International Law - LGS - LLM

- Masters Program in Business Administration - International Law - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Logistics and Supply Chain Management - LGS - MSc

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Logistics & Supply Chain Management - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Public Administration - LGS - MA

- Masters Program in Police Leadership and Management - LGS - MSc

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Public Administration - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Strategic Marketing - LGS - MSc

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Marketing - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Tourism and Hospitality Management - LGS - MSc

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Tourism & Hospitality - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Tourism & Hospitality - EIE - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Cyber Security - UCAM - MBA

- Masters Program in Business Administration - Data science - UCAM - MBA

All Bachelor Programs

- Bachelors Program in Business Management & Strategy - UOG - BA (Hons)

- Bachelors Program in Business Administration – eie – BBA

- Bachelors Program in Information Technology - UOG - BSc (Hons)

- Bachelors Program in Cyber Security - UOG - BSc (Hons)

- Bachelors Program in Tourism & Hospitality Management – eie – BA

- Bachelors Program in Accounting and Finance – eie – BA

All Professional Programs

- Professional Diploma in Asset-Based Lending - QUALIFI (Level-7)

- Professional Diploma in Accounting and Business - OTHM (Level-6)

- Professional Diploma in Wealth Management (Level-7)

- Professional Certificate in Financial Trading (Level-6)

- Professional Diploma in Capital Markets, Regulations, and Compliance (Level-7)

- Professional Program in Accounting and Finance – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Diploma in Executive Management - QUALIFI (Level-7)

- Professional Diploma in Strategic Management and Innovation - QUALIFI (Level-7)

- Professional Diploma in Business Management - OTHM (Level-6)

- Professional Diploma in Quality Management (Level-7)

- Professional Certificate in Security Management (Level-5)

- Professional Diploma for Construction Senior Management (Level-7)

- Professional Diploma in Operations Management (Level-7)

- Professional Diploma in Management Consulting (Level-7)

- Professional Program in Strategic Management and Leadership – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Program in Risk Management – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Program in Project Management – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Diploma in Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for Leadership - QUALIFI (Level-7)

- Professional Diploma in Early Learning and Childcare - QUALIFI (Level-5)

- Professional Certificate in Leading the Internal Quality Assurance of Assessment Processes and Practice - OTHM (Level-4)

- Professional Certificate in Research Methods - OTHM (Level-7)

- Professional Certificate in Academic and Professional Skills Development - OTHM (Level-6)

- Professional Diploma in Teaching and Learning - OTHM (Level-6)

- Professional Diploma in Career Guidance & Development (Level-7)

- Professional Diploma in Translation (Level-7)

- Professional Diploma in Education and Training - OTHM (Level-5)

- Professional Program in Education Management and Leadership – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Diploma in Cyber Security - QUALIFI (Level-4 & 5)

- Professional Diploma in Data Science - QUALIFI (Level-7)

- Professional Diploma in IT - E-commerce - QUALIFI (Level-4 & 5)

- Professional Diploma in IT - Networking - QUALIFI (Level-4 & 5)

- Professional Diploma in IT - Web Design - QUALIFI (Level-4 & 5)

- Professional Diploma in Information Technology - OTHM (Level-6)

- Professional Diploma in Health and Wellness Coaching - QUALIFI (Level-7)

- Professional Diploma in Psychology - OTHM (Level-5)

- Professional Diploma in Health and Social Care Management - OTHM (Level-6)

- Professional Program in Health & Social Care Management – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Diploma in Logistics and Supply Chain Management - OTHM (Level-6)

- Professional Diploma in Procurement and Supply Chain Management (Level-7)

- Professional Program in Logistics & Supply Chain Management – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Diploma in Tourism & Hospitality Management - OTHM (Level-6)

- Professional Certificate in Golf Club Management (Level-5)

- Professional Diploma in Facilities Management (Level-7)

- Professional Program in Tourism & Hospitality Management – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Diploma in Professional Marketing (Level-6)

- Professional Diploma in Brand Management (Level-7)

- Professional Diploma in Digital Marketing (Level-7)

- Professional Program in Coaching and Mentoring – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Program in Strategic Marketing – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Certificate in Paralegal (Level-7)

- Professional Program in International Business Law – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Certificate in Public Relations (Level-4)

- Professional Diploma in International Relations (Level-7)

- Professional Diploma in International Trade (Level-7)

- Professional Program in Public Administration – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Program in Police Leadership and Management – OTHM – Level 7

- Professional Program in Human Resource Management – OTHM – Level 7

All Bridge Program Programs

- Bridge Program - MBA - Public Administration - UCAM

- Bridge Program - MBA - Logistics & Supply Chain Management - UCAM

- Bridge Program - MBA - Tourism and Hospitality Management - UCAM

- Bridge Program - MBA - Project Management - UCAM

- Bridge Program - MBA - Human Resource Management - UCAM

- Bridge Program - MBA - Health & Safety Management - UCAM

Enquiry Form

Education and Training

Assignment-based vs examination-based evaluation systems

The current education system was developed in ancient times, refined and propagated during the colonial era. Currently, there are two types of evaluation systems that are popular among educational institutions: assignment-based and examination-based evaluation systems. The system and approach towards education have been reformed after the recent reforms in the education industry. The United Kingdom, having one of the finest education system in the world, has given preference to the assignment-based evaluation system. In most of its higher education programs, such as the PhD and Masters Degree Programs, assignments are the primary means of progression.

As assignment-based evaluation has become a standard in many fine education systems, the recent reforms in online learning have also considered this. Many prestigious institutes like SNATIKA have chosen this type of assessment system in their programs. Assessment only by assignments or by a mixture of assignments and examinations yields higher marks than assessment only by examinations (Source: John Richardson T.E. ). In this article, we will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of both assignment-based and examination-based evaluation systems.

Advantages of assignment-based evaluation

Source: Thought Catalog Unsplash

An assignment is a written or digitally created piece of academic work. It forces a learner to learn, practice, and demonstrate their progress and achievements in academics. An assignment-based evaluation system considers assignments written by the learners as the measure of learning, as opposed to an examination-based evaluation system. However, many institutes use both systems to varying degrees.

The assignment-based education is a preferred method for senior professionals that are working full-time jobs, have family commitments and have a flair for in-depth education in their industry. In the case of SNATIKA , the immersive syllabus coupled with experience on the part of the learner can make the assignments one of the most intellectually challenging and, at the same time, enjoyable.

Writing assignments is an intellectually challenging task. Especially in advanced programs like PhD and Masters Degree programs, assignments require intensive research on the topics. The proficiency, understanding, and expertise on the subject can greatly vary, depending on the type and length of the assignment. Here are the advantages of this evaluation.

1. Assignment-based evaluation enhances cognitive and analytical capabilities

An assignment needs careful planning. To succeed, a learner needs to connect data from different sources. In doing so, the learner develops logical reasoning and critical thinking. Connecting different pieces of information and putting them together is a mental exercise. Often, it requires the learner to think unconventionally. These abilities are put to the test in educational institutes like SNATIKA , where you are required to write an 12,000-word consultancy project report to earn the UK Masters. Such an intellectual challenge can refine the learner's research and analytical skills and give a range of insights and perspectives into the industry.

2. The learner becomes research-oriented

Writing an assignment needs genuine, scientifically proven, and practical sources for the claims, numbers, and hypotheses mentioned in the assignment. Though the digital world has made information available at the fingertips, it is hard to find genuine news, statistics, or research from the relevant industry. Furthermore, false news and propaganda are on the rise. Fake news has become a major concern for the internal security of most nations (Source: PNAS.org ). It takes time and effort to assess the veracity of misinformation, fake news, and claims.

This internet misinformation problem can pose a threat as well as a learning opportunity to assignment writers. Though it takes some time to find genuine sources, with time, learners will develop a flair for identifying the fake from the genuine on the internet. In a world devoid of such a moral compass in the news, this research-oriented, fact-finding skill can be an asset for the learner.

Moreover, the learner will gain in-depth knowledge and understanding of the industry with the assignments. As sources and research become the foundation of assignments, the learner will gain overall mastery of their industry. This attitude will help the learner in future jobs or businesses as it eliminates guesswork, assumptions, and hypotheses.

3. It increases understanding of the subject.

Typically, an assignment needs the complete involvement of the learner to write. This includes all the facilities of the brain like thinking, reasoning, problem-solving, writing, fact-checking, and intuition. Above all, to write something, the learner must have a solid understanding of the topic to the degree of expertise. Copy-pasting or rote rehearsals are simply not an option for writing an original assignment, free from plagiarism. As this forces the learner to completely grasp the subject, their understanding becomes deeper and more robust. Also, assignments help the learner to gain more insights through standing in the shoes of other industry experts, scholars, and researchers.

4. Improves technical writing abilities

Writing an original assignment on any subject stimulates the writer's brain. Without proper structure, flow, or facts, such writing can become tiresome to the reader, who, in this case, is the evaluator. However, due to a deep understanding of the subject, a learner can easily acquire these writing qualities as time progresses. Through trial and error, learners develop and refine their technical writing skills.

Technical writing can be useful in many other areas of the learner's professional life. In this digital age, writing research-based technical articles can change the perspectives of customers, business owners, stockholders, and critics alike. It also enables the learner to articulate their thoughts, ideas, and criticisms in a powerful way to their audience.

5. Promotes originality

Plagiarism is an epidemic. With the exponential popularity of the internet, originality is in short supply. Due to the demand for content and the sheer size of the internet, people resort to copy-pasting content from others. Often, these go unnoticed because of the huge user base. However, it denies the original creator the recognition, money, or popularity that they are entitled to. Saving one's original content from the invasive plagiarists is a daunting task for intellectual property owners and content creators.

Writing an original assignment that had plagiarism limits forces the learner to identify the immorality of copy-pasting. It also teaches the learner to cite their sources and give the original authors the credit and recognition they deserve. In a world where piracy is destroying industries like movies, songs, and photographs, plagiarism-free assignments might cause a revolution.

Related Blog - Commercialisation of Education vs State-Controlled Education

Disadvantages of assignment-based evaluation

1. university guidelines.

Learners sometimes struggle with understanding the university guidelines on writing assignments. International learners initially find it difficult to understand complex rules, word limits, and the progression process of assignment-based education systems. However, once the learning curve flattens, this can be less bothersome for these learners.

2. Language and accent differences

International learners struggle with keeping up with the language standards, especially the accent of the university. Non-native learners often struggle with expressing their thoughts and ideas in writing. Also, following the complex grammar rules of the language can be a problem.

3. Difficulty with specific skills

If the learner is new to the assignment-based evaluation system, they will struggle with the extra skills that are needed in writing the assignment. They struggle with researching on the internet, where misinformation and clickbait are plentiful. They struggle to connect their learning with reasoning or to express their ideas through words.

4. Plagiarism

For many learners, writing plagiarism-free content can become a major hurdle. Due to poor research and writing skills, plagiarism levels can go higher than the set limitations. Those learners who are new to plagiarism checking find it hard to paraphrase, cite, and edit their academic work.

However, this problem can be easily overcome with modern AI software like Grammarly , Duplichecker , etc. Many such online tools help in paraphrasing and citing the source. Even then, human intervention is necessary to adjust the assignment to the right accent and tone.

5. Time-consuming for educators

Preparing the assignment questions and pointers is a time-consuming task. Also, evaluating the learner's assignments is even more time-consuming. This can add more complexity to educational institutions where the teacher-to-learner ratio is smaller. As a result, teachers will struggle to make ends meet in terms of time limitations.

Related Blog - How EdTech is changing the world

The advantages of examination-based evaluation

Source: Museums Victoria Unsplash

1. Self-assessment

Examinations are used to quickly measure learning. Learners can easily determine the quality of their study techniques through exams, tests, and quizzes. These help the learner and the educator to identify and avoid key teaching pitfalls faster than an assignment-based evaluation system.

2. Easy detection of teaching flaws

The examination-based evaluation can detect not only key areas where the learner is failing but also the teacher’s and teaching system's overall performance as well. Similar to the self-assessment by a student, exams can also be used by educators to improve their styles.

3. Personality growth

Competitive environment : Examinations create a competitive environment that reflects similar real-life scenarios. Here, learners are educated to provide results that satisfy some set standards, though they are rigid and outdated. This helps learners thrive in competitive environments.

Memory improvement : Exams increase learners’ memory. It introduces them to a range of memory techniques like rote rehearsals, mnemonics, visualisation, etc. Contrary to popular opinion, these memorization techniques can benefit the brain, thinking, and reasoning of the learner in many ways (Source: Forbes ).

Stress management : Examinations induce stress in learners. The need to excel, the possibility of failure and its consequences keep many learners awake at night. However, this can also help in learning and thriving under such pressure.

Such benefits can help the learner develop their competence and performance. This helps with overall personality development.

4. Scholarships and employment opportunities

Finally, examinations and their grades, ranks, or marks can get you scholarships if you are planning to continue your education and job opportunities if you are job hunting. Even today, higher ranks and marks are the sole measure of human intelligence in many countries and companies. This benefits the learner in landing better entry-level jobs.

Related Blog - 10 Learning Tips for Senior Professionals

Disadvantages of examination based evaluation

1. examinations have become a formality..

There is always the risk in the examination-based education system that the learner only learns the syllabus to pass and obtain the degree or certification. As a result, the learner focuses only on some key areas of the syllabus and uses memorization instead of understanding the subject to pass the exam. This defeats the purpose of education. As education is viewed as solely a formality to get a job or a seat in a prestigious institution, education loses its meaning. After passing out, most learners won’t even remember what they have learnt. Education that does not develop the learner's knowledge and thinking is only a waste of time and effort.

2. Examinations cause stress.

In many cases, examinations cause anxiety in learners. As exams typically test the learner's knowledge of the whole syllabus on a single day, it causes learning overload or revision overload, which results in stress. This is especially a problem for learners struggling with procrastination and poor time management skills.

In many countries, like India, suicide due to failure in exams is a major drawback of examination-based evaluation. Because of this, over 4,000 students lost their lives by suicide between 2017 and 2019 (Source: The Hindustan Times ). This happens due to the social stigma against those who have failed examinations. Unhealthy competition between institutions, and unreasonable expectations of self, family, and society are some of the reasons why many learners lose their precious lives to suicide.

3. Unhealthy rivalry

Examinations are a primary source of the status quo for many prestigious institutions. To secure top ranks, these institutions admit only competitive individuals, which side-lines other learners who are as much in need of quality education as others. This applies to teaching staff as well. Overall, examinations can cause immense stress for both learners and staff, for better or worse. Competition between such institutes leaves a negative effect on their students about the idea of education.

Related Blog - Funding your Masters in Education Management

The SNATIKA pedagogy

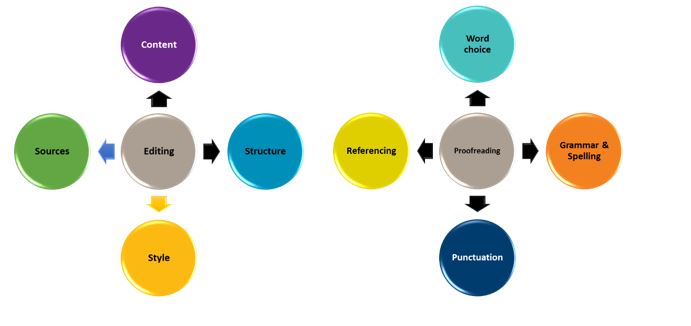

SNATIKA combines both these evaluation methods in its pedagogy. The primary evaluation method for learning is assignment-based evaluation. The same is used to evaluate the progress of SNATIKA learners in all the programs. However, SNATIKA uses quizzes for each unit to help learners assess their progress. A quiz in each unit tests the learners' knowledge and helps in identifying the gaps immediately. However, this is only for personal assessment rather than for university assessment. As a result, learners gain robust learning experiences without leaving out the advantages of either of these two evaluation methods.

Both assignment-based evaluation and examination-based evaluation have their merits and demerits. To be successful, learners and educators need to play the learning game to the strengths of both types of systems.

While the assignment-based evaluation develops critical academic and life skills and deepens the thinking capacity of a learner, the examination-based evaluation creates a competitive environment and a drive to perform better in education. However, both systems will fail in the absence of a true learning spirit on the part of the learner. Learning solely for grades, marks, or qualifications defeats the purpose of education. Care must be taken to truly employ both systems to independently develop the thinking capacity, skills, and knowledge of the learner.

While both systems have their own pros and cons, a mixed system carefully wrought according to the needs of learners can be the ideal system for learning. With decades of education experience, our founders at SNATIKA have developed a smart pedagogy that uses both systems to make your crucial higher educational qualification pursuit an enjoyable learning experience for senior learners. Visit SNATIKA and explore our range of prestigious international programs in the higher education category.

Related Blog - How 5G will Transform the E-learning Industry

RECENT POSTS

- Why You Might Need a Certificate in Research Methods

- Why Pursue a Diploma in Teaching and Learning

- Why Internal Quality Assurance is Important for Businesses

- Why Do We Need Strong and Well-Qualified Education Managers

- Why Continuing Professional Development is Essential for Leaders

- What does a Masters in Education Management and Leadership Program Teach You?

- Types of Translation

- Types of Research Methods

- Types of Mentoring

- Translating Tips for Website and App Localisation Process

Contact Information

- +91 8047183355 +234 1 8880 209 +27 21 825 9877 + 1 347 855 4980 + 44 20 3287 6900

- [email protected]

Connect with us on

Quick links.

COPYRIGHT © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

London School of Business and Administration

- Browse all Courses

- BA (Hons) ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE

- BA (Hons) Business (Tourism)

- BA (Hons) International Hospitality Business Management

- BSc (Hons) Cyber Security and Networking

- BSc (Hons) Business Computing and Information Systems

- MSc Human Resource Management

- BSc (Hons) Cyber Security

- MSc Project Management

- MSc Finance and Management

- BSc (Hons) Integrative Health and Social Care

- MBA Education Leadership and Management

- LLM International Business Law and Management

- ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE

- COMPUTING & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

- DIGITAL MARKETING

- EDUCATION, TRAINING & TEACHING

- ENGINEERING

- EQUALITY AND DIVERSITY

- HEALTH AND SAFETY

- HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE

- HOTEL MANAGEMENT

- HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

- LOGISTICS AND SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT

- OIL AND GAS

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT

- RELIGIOUS STUDIES

- SALES-MARKETING

- TRAVEL AND TOURISM

- Cyber Security

- EDUCATION AND TRAINING HIGH CREDITS

- HEALTH & SOCIAL CARE

- LOGISTICS AND SUPPLY CHAIN

- MARKETING HIGH CREDITS

- Project Management

- TOURISM & HOSPITALITY

- WHY CHOOSE LSBA

- BENEFITS OF STUDYING WITH US

- SMART LEARNING

- ASSIGNMENT BASED LEARNING

- RECOGNITION AND PARTNERSHIP

- WORKING WITH US

- WE ARE AVAILABLE 24/7 TO ASSIST YOU

Assignment Based Learning

London School of International Business (LSIB) uses an assessment strategy which includes assignment-based learning. We believe in assignments and assessments as a key aspects of learning: completing an assignment is an opportunity to demonstrate your achievements. LSIB will offer you feedback on assignments as to allow you to measure your achievement in relation to the standards set by the course and the college. LSIB has devised this Assignments and Assessment Policy to set out what is required and expected of both students and staff. This allows to ensure that all students have equal opportunities to demonstrate what they can do, and to receive accurate and useful feedback on their work.

- Overview + Features

- Propello Science 6-8

- Propello IB MYP Science

- Propello ELA 6-8

- Science Booster Packs

- Administrators

- Propello Press Blog

- Free Ebooks for Educators

- Education Uncharted Podcast

How to Use Project-Based Assessments (PBAs) in Education

by The Propello Crew on Nov 2, 2023 9:00:00 AM

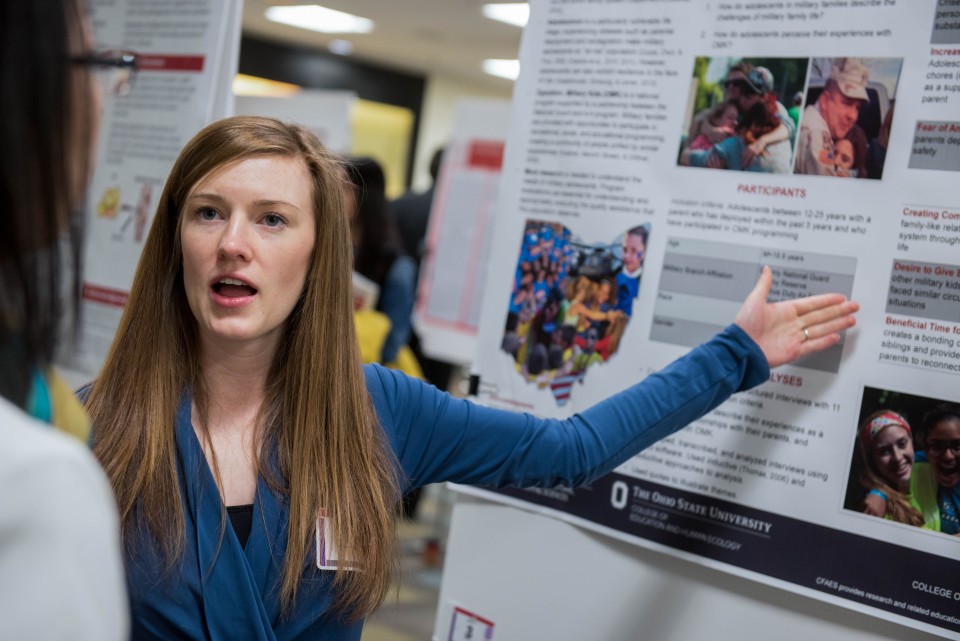

Over the past several years, educators have increasingly adopted personalized, student-centered teaching practices to ensure they reach and engage a broad spectrum of learners. Yet, when evaluating students’ knowledge and grasp of new concepts, many schools still rely on traditional assessment methods like tests and quizzes. While these assessments have their place, they’re not always the best indicator of how well students understand materials or whether they can apply their new knowledge in a real-world context. Instead, it can be more beneficial (and enjoyable) for students to participate in project-based assessments: activities that require them to demonstrate their grasp of new information and skills in ways that promote further development and deep learning .

What are Project-Based Assessments?

Project-based assessments (PBAs) are the means through which teachers measure student knowledge gained via project-based learning (PBL) — a student-centered teaching approach that uses engaging, real-world applications and hands-on learning to help students build knowledge while strengthening critical thinking and problem-solving skills. In classrooms that use PBL, students often work together to answer curriculum-relevant questions and solve challenges, preparing them to become adept communicators and collaborators in their future lives and careers. Instead of end-of-unit tests, they are assessed through group or independent projects. For example, in a unit about environmental pollution, students might be asked to prepare and present a strategy for reducing pollutants in their community. Or, to learn about the Supreme Court, you might hold a mock hearing where students research and argue for or against one side of a historic case.

One of the best benefits of using PBAs is that you can vary the format depending on the subject, unit, skills involved, and learning objective. Examples of PBAs include:

- Presentations

- Labs and experiments

- Physical crafts and creations

- Written reports

- Classroom debates or mock trials

- Plays and performances

- Journals, blogs, or photo logs

- Videos or podcasts

- Plans, strategies, or campaigns

How Do Project-Based Assessments Differ from Traditional Assessments?

In PBL, teachers act as guides, supporting students as they define problems and work to ideate and test solutions. Instead of lecturing, teachers ask probing questions that directly engage students , ignite their creativity and critical thinking, and frame challenges in the proper contexts. And instead of using traditional assessment methods like tests and quizzes, teachers assess student learning by evaluating their projects. However, it’s important to recognize that PBAs are different from the projects teachers sometimes assign students after covering curriculum material in a traditional way. Unlike those lighter projects, a project-based assessment is the primary means for covering a unit.

In other words, students learn the material by completing a project, which may involve multiple phases and span several weeks. Assessments may include a combination of group collaboration and independent work and can even cover numerous subjects or curriculum areas. For projects with multiple steps, teachers might assess students at the end of each phase and on the final product.

PBAs differ from tests and quizzes, which can fall short in deciphering between actual knowledge and rote memorization. Instead, they (PBAs) help students build knowledge and challenge them to apply their new knowledge in meaningful ways.

What Does the Research Say About Project-Based Assessments in Education?

While transitioning to PBL from traditional methods can take some getting used to, research shows it’s well worth the effort, boosting student engagement, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills. In a study of middle school students , 7th and 8th graders taught via PBL displayed higher academic achievement in math and reading than non-PBL peers. And a 2020 study found that PBL techniques improve student engagement by supporting knowledge and information sharing and discussion. Additionally, a study of vocational high school students found that PBL increased problem-solving abilities and learning motivation, while a 2019 study published in the International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research found multidisciplinary integrated PBL improved critical thinking and collaboration skills.

PBL can also make learning more fun for students, potentially reducing stress — particularly for those with test anxiety — while helping them excel academically. In a 2023 study where students’ exams were replaced with PBAs, students not only received higher marks but also reported a better learning experience.

Excelling with PBAs in Your Classroom

We know what you’re probably thinking. “This sounds great in theory, but how do I successfully introduce PBAs into my classroom(s)?”

Here are a few recommendations:

- Don’t change too much too soon PBAs — and project-based learning in general — isn’t something you swap to overnight. Instead, it’s better to introduce the approach slowly, experiment with it, and tweak it over time. You might start by trying PBL for a unit on the solar system, switching out your usual lectures and end-unit test with a multi-week classroom project that covers the same standards. For example, Propello includes an earth/space science project in which students demonstrate their comprehension of geologic time, Earth’s history, and the formation of the solar system. The project also challenges students to use data collection and analysis to predict its future and build a 3D model.

- Set clear parameters Define your scope. For example, how many weeks will the project take? How many priority standards will the project cover? What criteria or rubric will you use to evaluate students’ projects? In Propello, each project lists how many class periods it will take and approximately how long each session will require so you can plan accordingly. For example, a Propello life science PBA on mapping inheritance should span 4 to 5 class periods of 45 minutes each. By setting clear expectations, you and your students can get accustomed to the new pace and way of learning.

- Make it your own Remember that PBAs won’t look the same for every classroom (or even every student) and will likely vary from year to year as you become more familiar with what works best. Fortunately, the flexible nature of project-based assessments makes it easy to build in modifications, learning accommodations , and differentiation. Some teachers even present students with a “menu” of projects so they can select the assessment that best aligns with their interests, skills, and how they learn.

- Leverage supportive tools One of the biggest challenges associated with project-based assessments in education is that it can be labor-intensive for teachers. Projects are often more complicated to evaluate than a multiple-choice test, and developing fresh ideas for assessments and ensuring projects include modifications for different learners requires a lot of time and mental bandwidth. This is where technology can help. Propello was designed by educators to provide teachers with customizable and flexible lesson planning for active learning approaches like PBL. With built-in assessment options and embedded scaffolding, you’ll have all the support you need to succeed while conserving your energy.

Interested in leveraging PBAs in your classroom but not sure where to start? Sign up for a free Propello account to access hundreds of customized activities and projects.

- #scienceinstruction (15)

- #educationuncharted (11)

- #professionaldevelopment (9)

- #whypropello (9)

- #science (6)

- #curriculum (5)

- #differentiatedinstruction (4)

- #pedagogy (4)

- #learningscience (3)

- #lessonplan (3)

- #PropelloNews (2)

- #artificialintelligence (2)

- #edspace (2)

- #makingmeaning (2)

- #studentengagement (2)

- #cognitiveload (1)

- #quietquitting (1)

- #solareclipse (1)

- #standardsbasedgrading (1)

- #teacherappreciation (1)

- April 2024 (1)

- March 2024 (3)

- January 2024 (1)

- December 2023 (2)

- November 2023 (4)

- October 2023 (3)

- September 2023 (4)

- August 2023 (5)

- July 2023 (3)

- June 2023 (5)

- May 2023 (6)

- April 2023 (4)

- March 2023 (5)

- February 2023 (2)

- January 2023 (4)

- December 2022 (3)

- November 2022 (4)

- October 2022 (1)

- September 2022 (1)

- August 2022 (2)

Subscribe by email

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Instructional Technologies

- Teaching in All Modalities

Designing Assignments for Learning

The rapid shift to remote teaching and learning meant that many instructors reimagined their assessment practices. Whether adapting existing assignments or creatively designing new opportunities for their students to learn, instructors focused on helping students make meaning and demonstrate their learning outside of the traditional, face-to-face classroom setting. This resource distills the elements of assignment design that are important to carry forward as we continue to seek better ways of assessing learning and build on our innovative assignment designs.

On this page:

Rethinking traditional tests, quizzes, and exams.

- Examples from the Columbia University Classroom

- Tips for Designing Assignments for Learning

Reflect On Your Assignment Design

Connect with the ctl.

- Resources and References

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2021). Designing Assignments for Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/teaching-with-technology/teaching-online/designing-assignments/

Traditional assessments tend to reveal whether students can recognize, recall, or replicate what was learned out of context, and tend to focus on students providing correct responses (Wiggins, 1990). In contrast, authentic assignments, which are course assessments, engage students in higher order thinking, as they grapple with real or simulated challenges that help them prepare for their professional lives, and draw on the course knowledge learned and the skills acquired to create justifiable answers, performances or products (Wiggins, 1990). An authentic assessment provides opportunities for students to practice, consult resources, learn from feedback, and refine their performances and products accordingly (Wiggins 1990, 1998, 2014).

Authentic assignments ask students to “do” the subject with an audience in mind and apply their learning in a new situation. Examples of authentic assignments include asking students to:

- Write for a real audience (e.g., a memo, a policy brief, letter to the editor, a grant proposal, reports, building a website) and/or publication;

- Solve problem sets that have real world application;

- Design projects that address a real world problem;

- Engage in a community-partnered research project;

- Create an exhibit, performance, or conference presentation ;

- Compile and reflect on their work through a portfolio/e-portfolio.

Noteworthy elements of authentic designs are that instructors scaffold the assignment, and play an active role in preparing students for the tasks assigned, while students are intentionally asked to reflect on the process and product of their work thus building their metacognitive skills (Herrington and Oliver, 2000; Ashford-Rowe, Herrington and Brown, 2013; Frey, Schmitt, and Allen, 2012).

It’s worth noting here that authentic assessments can initially be time consuming to design, implement, and grade. They are critiqued for being challenging to use across course contexts and for grading reliability issues (Maclellan, 2004). Despite these challenges, authentic assessments are recognized as beneficial to student learning (Svinicki, 2004) as they are learner-centered (Weimer, 2013), promote academic integrity (McLaughlin, L. and Ricevuto, 2021; Sotiriadou et al., 2019; Schroeder, 2021) and motivate students to learn (Ambrose et al., 2010). The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning is always available to consult with faculty who are considering authentic assessment designs and to discuss challenges and affordances.

Examples from the Columbia University Classroom

Columbia instructors have experimented with alternative ways of assessing student learning from oral exams to technology-enhanced assignments. Below are a few examples of authentic assignments in various teaching contexts across Columbia University.

- E-portfolios: Statia Cook shares her experiences with an ePorfolio assignment in her co-taught Frontiers of Science course (a submission to the Voices of Hybrid and Online Teaching and Learning initiative); CUIMC use of ePortfolios ;

- Case studies: Columbia instructors have engaged their students in authentic ways through case studies drawing on the Case Consortium at Columbia University. Read and watch a faculty spotlight to learn how Professor Mary Ann Price uses the case method to place pre-med students in real-life scenarios;

- Simulations: students at CUIMC engage in simulations to develop their professional skills in The Mary & Michael Jaharis Simulation Center in the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and the Helene Fuld Health Trust Simulation Center in the Columbia School of Nursing;

- Experiential learning: instructors have drawn on New York City as a learning laboratory such as Barnard’s NYC as Lab webpage which highlights courses that engage students in NYC;

- Design projects that address real world problems: Yevgeniy Yesilevskiy on the Engineering design projects completed using lab kits during remote learning. Watch Dr. Yesilevskiy talk about his teaching and read the Columbia News article .

- Writing assignments: Lia Marshall and her teaching associate Aparna Balasundaram reflect on their “non-disposable or renewable assignments” to prepare social work students for their professional lives as they write for a real audience; and Hannah Weaver spoke about a sandbox assignment used in her Core Literature Humanities course at the 2021 Celebration of Teaching and Learning Symposium . Watch Dr. Weaver share her experiences.

Tips for Designing Assignments for Learning

While designing an effective authentic assignment may seem like a daunting task, the following tips can be used as a starting point. See the Resources section for frameworks and tools that may be useful in this effort.

Align the assignment with your course learning objectives

Identify the kind of thinking that is important in your course, the knowledge students will apply, and the skills they will practice using through the assignment. What kind of thinking will students be asked to do for the assignment? What will students learn by completing this assignment? How will the assignment help students achieve the desired course learning outcomes? For more information on course learning objectives, see the CTL’s Course Design Essentials self-paced course and watch the video on Articulating Learning Objectives .

Identify an authentic meaning-making task

For meaning-making to occur, students need to understand the relevance of the assignment to the course and beyond (Ambrose et al., 2010). To Bean (2011) a “meaning-making” or “meaning-constructing” task has two dimensions: 1) it presents students with an authentic disciplinary problem or asks students to formulate their own problems, both of which engage them in active critical thinking, and 2) the problem is placed in “a context that gives students a role or purpose, a targeted audience, and a genre.” (Bean, 2011: 97-98).

An authentic task gives students a realistic challenge to grapple with, a role to take on that allows them to “rehearse for the complex ambiguities” of life, provides resources and supports to draw on, and requires students to justify their work and the process they used to inform their solution (Wiggins, 1990). Note that if students find an assignment interesting or relevant, they will see value in completing it.

Consider the kind of activities in the real world that use the knowledge and skills that are the focus of your course. How is this knowledge and these skills applied to answer real-world questions to solve real-world problems? (Herrington et al., 2010: 22). What do professionals or academics in your discipline do on a regular basis? What does it mean to think like a biologist, statistician, historian, social scientist? How might your assignment ask students to draw on current events, issues, or problems that relate to the course and are of interest to them? How might your assignment tap into student motivation and engage them in the kinds of thinking they can apply to better understand the world around them? (Ambrose et al., 2010).

Determine the evaluation criteria and create a rubric

To ensure equitable and consistent grading of assignments across students, make transparent the criteria you will use to evaluate student work. The criteria should focus on the knowledge and skills that are central to the assignment. Build on the criteria identified, create a rubric that makes explicit the expectations of deliverables and share this rubric with your students so they can use it as they work on the assignment. For more information on rubrics, see the CTL’s resource Incorporating Rubrics into Your Grading and Feedback Practices , and explore the Association of American Colleges & Universities VALUE Rubrics (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education).

Build in metacognition

Ask students to reflect on what and how they learned from the assignment. Help students uncover personal relevance of the assignment, find intrinsic value in their work, and deepen their motivation by asking them to reflect on their process and their assignment deliverable. Sample prompts might include: what did you learn from this assignment? How might you draw on the knowledge and skills you used on this assignment in the future? See Ambrose et al., 2010 for more strategies that support motivation and the CTL’s resource on Metacognition ).

Provide students with opportunities to practice

Design your assignment to be a learning experience and prepare students for success on the assignment. If students can reasonably expect to be successful on an assignment when they put in the required effort ,with the support and guidance of the instructor, they are more likely to engage in the behaviors necessary for learning (Ambrose et al., 2010). Ensure student success by actively teaching the knowledge and skills of the course (e.g., how to problem solve, how to write for a particular audience), modeling the desired thinking, and creating learning activities that build up to a graded assignment. Provide opportunities for students to practice using the knowledge and skills they will need for the assignment, whether through low-stakes in-class activities or homework activities that include opportunities to receive and incorporate formative feedback. For more information on providing feedback, see the CTL resource Feedback for Learning .

Communicate about the assignment

Share the purpose, task, audience, expectations, and criteria for the assignment. Students may have expectations about assessments and how they will be graded that is informed by their prior experiences completing high-stakes assessments, so be transparent. Tell your students why you are asking them to do this assignment, what skills they will be using, how it aligns with the course learning outcomes, and why it is relevant to their learning and their professional lives (i.e., how practitioners / professionals use the knowledge and skills in your course in real world contexts and for what purposes). Finally, verify that students understand what they need to do to complete the assignment. This can be done by asking students to respond to poll questions about different parts of the assignment, a “scavenger hunt” of the assignment instructions–giving students questions to answer about the assignment and having them work in small groups to answer the questions, or by having students share back what they think is expected of them.

Plan to iterate and to keep the focus on learning

Draw on multiple sources of data to help make decisions about what changes are needed to the assignment, the assignment instructions, and/or rubric to ensure that it contributes to student learning. Explore assignment performance data. As Deandra Little reminds us: “a really good assignment, which is a really good assessment, also teaches you something or tells the instructor something. As much as it tells you what students are learning, it’s also telling you what they aren’t learning.” ( Teaching in Higher Ed podcast episode 337 ). Assignment bottlenecks–where students get stuck or struggle–can be good indicators that students need further support or opportunities to practice prior to completing an assignment. This awareness can inform teaching decisions.

Triangulate the performance data by collecting student feedback, and noting your own reflections about what worked well and what did not. Revise the assignment instructions, rubric, and teaching practices accordingly. Consider how you might better align your assignment with your course objectives and/or provide more opportunities for students to practice using the knowledge and skills that they will rely on for the assignment. Additionally, keep in mind societal, disciplinary, and technological changes as you tweak your assignments for future use.

Now is a great time to reflect on your practices and experiences with assignment design and think critically about your approach. Take a closer look at an existing assignment. Questions to consider include: What is this assignment meant to do? What purpose does it serve? Why do you ask students to do this assignment? How are they prepared to complete the assignment? Does the assignment assess the kind of learning that you really want? What would help students learn from this assignment?

Using the tips in the previous section: How can the assignment be tweaked to be more authentic and meaningful to students?

As you plan forward for post-pandemic teaching and reflect on your practices and reimagine your course design, you may find the following CTL resources helpful: Reflecting On Your Experiences with Remote Teaching , Transition to In-Person Teaching , and Course Design Support .

The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) is here to help!

For assistance with assignment design, rubric design, or any other teaching and learning need, please request a consultation by emailing [email protected] .

Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT) framework for assignments. The TILT Examples and Resources page ( https://tilthighered.com/tiltexamplesandresources ) includes example assignments from across disciplines, as well as a transparent assignment template and a checklist for designing transparent assignments . Each emphasizes the importance of articulating to students the purpose of the assignment or activity, the what and how of the task, and specifying the criteria that will be used to assess students.

Association of American Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) offers VALUE ADD (Assignment Design and Diagnostic) tools ( https://www.aacu.org/value-add-tools ) to help with the creation of clear and effective assignments that align with the desired learning outcomes and associated VALUE rubrics (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education). VALUE ADD encourages instructors to explicitly state assignment information such as the purpose of the assignment, what skills students will be using, how it aligns with course learning outcomes, the assignment type, the audience and context for the assignment, clear evaluation criteria, desired formatting, and expectations for completion whether individual or in a group.

Villarroel et al. (2017) propose a blueprint for building authentic assessments which includes four steps: 1) consider the workplace context, 2) design the authentic assessment; 3) learn and apply standards for judgement; and 4) give feedback.

References

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., & DiPietro, M. (2010). Chapter 3: What Factors Motivate Students to Learn? In How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching . Jossey-Bass.

Ashford-Rowe, K., Herrington, J., and Brown, C. (2013). Establishing the critical elements that determine authentic assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 39(2), 205-222, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.819566 .

Bean, J.C. (2011). Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom . Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Frey, B. B, Schmitt, V. L., and Allen, J. P. (2012). Defining Authentic Classroom Assessment. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. 17(2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.7275/sxbs-0829

Herrington, J., Reeves, T. C., and Oliver, R. (2010). A Guide to Authentic e-Learning . Routledge.

Herrington, J. and Oliver, R. (2000). An instructional design framework for authentic learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(3), 23-48.

Litchfield, B. C. and Dempsey, J. V. (2015). Authentic Assessment of Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 142 (Summer 2015), 65-80.

Maclellan, E. (2004). How convincing is alternative assessment for use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 29(3), June 2004. DOI: 10.1080/0260293042000188267

McLaughlin, L. and Ricevuto, J. (2021). Assessments in a Virtual Environment: You Won’t Need that Lockdown Browser! Faculty Focus. June 2, 2021.

Mueller, J. (2005). The Authentic Assessment Toolbox: Enhancing Student Learning through Online Faculty Development . MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching. 1(1). July 2005. Mueller’s Authentic Assessment Toolbox is available online.

Schroeder, R. (2021). Vaccinate Against Cheating With Authentic Assessment . Inside Higher Ed. (February 26, 2021).

Sotiriadou, P., Logan, D., Daly, A., and Guest, R. (2019). The role of authentic assessment to preserve academic integrity and promote skills development and employability. Studies in Higher Education. 45(111), 2132-2148. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1582015

Stachowiak, B. (Host). (November 25, 2020). Authentic Assignments with Deandra Little. (Episode 337). In Teaching in Higher Ed . https://teachinginhighered.com/podcast/authentic-assignments/

Svinicki, M. D. (2004). Authentic Assessment: Testing in Reality. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 100 (Winter 2004): 23-29.

Villarroel, V., Bloxham, S, Bruna, D., Bruna, C., and Herrera-Seda, C. (2017). Authentic assessment: creating a blueprint for course design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 43(5), 840-854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1412396

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice . Second Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wiggins, G. (2014). Authenticity in assessment, (re-)defined and explained. Retrieved from https://grantwiggins.wordpress.com/2014/01/26/authenticity-in-assessment-re-defined-and-explained/

Wiggins, G. (1998). Teaching to the (Authentic) Test. Educational Leadership . April 1989. 41-47.

Wiggins, Grant (1990). The Case for Authentic Assessment . Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation , 2(2).

Wondering how AI tools might play a role in your course assignments?

See the CTL’s resource “Considerations for AI Tools in the Classroom.”

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”